Art & Exhibitions

Artist and Chef Nathan Myhrvold’s New Photos Bring Food Into Intimate Focus

The Microsoft CTO-turned-photographer is hosting his first solo show in New York.

Few artists have a biography as varied as Nathan Myhrvold. The photographer, scientist, chef, and author of the award-winning Modernist Cuisine cookbooks opened his first New York City solo show this week inside—appropriately—a delicious Japanese restaurant.

When I asked him to define himself, Myhrvold told me it depended on the context. “I go to dinosaur conferences, and when I’m there, I would describe myself as a paleontologist. I do research in astronomy and when I go to those things, I am an astronomer. And when I am talking to people at my art galleries or doing an interview like this, I’m an artist.”

Myhrvold, age 65, got a Ph.D. in applied mathematics at New Jersey’s Princeton University and did a postdoctoral fellowship with Stephen Hawking. Next, he cofounded a computer start-up that Microsoft purchased in 1986. He worked for the company for 13 years, serving as its first chief technology officer before retiring in 1999.

Now, “Intention and Detail” at the Gallery, a Japanese restaurant and art gallery from chef Hiroki Odo, is Myhrvold’s first formal art exhibition. (He’s shown his photographs at museums before, but at institutions dedicated to science, not art.)

Nathan Myhrvold, Yumepirika, a photo of premium Japanese white rice grown by Mr. Tomo. Photo by Nathan Myhrvold/Modernist Cuisine Gallery LLC.

Odo opened his namesake Flatiron District restaurant in late 2018, earning two Michelin stars and an effusive three-star New York Times review. There’s a bar called Hall in front of the kaiseki dining counter, and a speakeasy lounge tucked in back. In 2021, Odo expanded next door with the Gallery, as a means of combining his passion for art and design with his love of the culinary world.

Myhrvold, with his specialty of food photography, was a natural fit for the space—although when the chef reached out about the possibility of a show, he did have some notes.

“Nathan Myhrvold: Intention and Detail” at the Gallery by Odo, New York. Photo by Olive Mirra/Modernist Cuisine Gallery LLC.

“He said, ‘I love your photographs, but you don’t have all that much Japanese food or Japanese ingredients.’ So I said, ‘well, I can fix that,'” Myhrvold said.

Already planning a photography trip to Borneo from his home in Seattle, it was easy for Myhrvold to extend a layover in Japan. On the outskirts of Tokyo in Minato, he spent a day documenting the production of mame daifuku, a traditional Japanese dessert of red bean paste wrapped in mochi, made from pounded rice, at Matsushimaya. Myhrvold wanted to celebrate the craft of old-fashioned production processes still in use in Japan, which, despite modernization, boasts many businesses that are hundreds of years old.

“It was fascinating to see them work. There are machines for a couple of things, like pounding the rice, but for almost everything else, they do it all by hand,” he recalled, noting that the trickiest thing about the shoot was simply finding a good vantage point to take photos in the business’s tight, efficiently organized quarters.

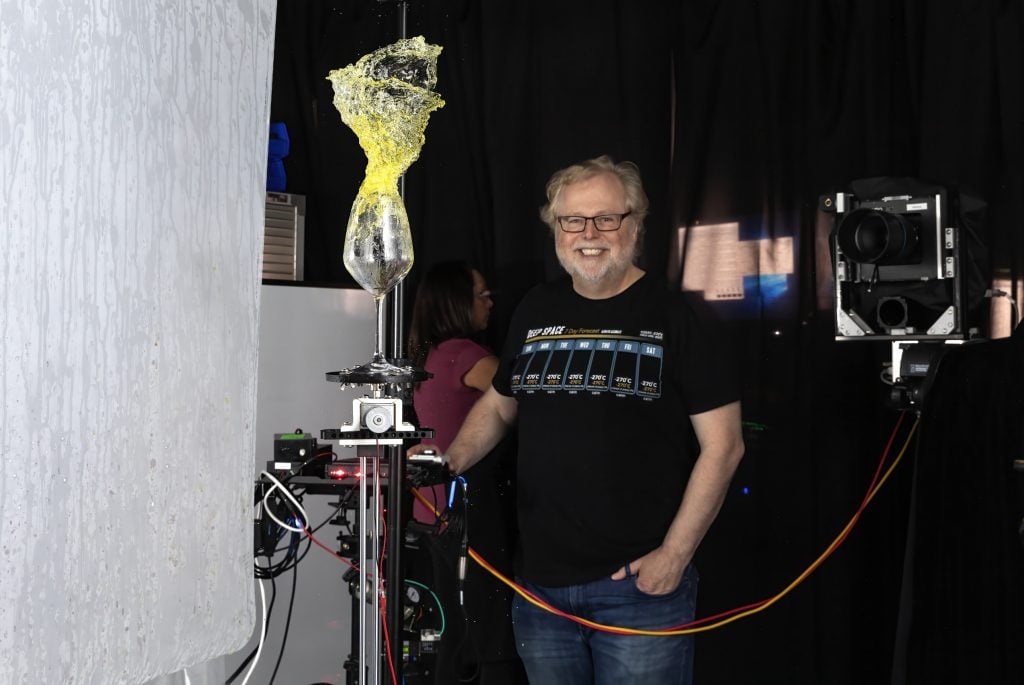

Nathan Myhrvold taking one of his frozen-motion photographs of wine. Photo courtesy of the Cooking Lab, LLC.

Back in Seattle, where he runs the Cooking Lab, the culinary research and development lab that self-publishes his books, Myhrvold also took photos under the microscope of typical Japanese ingredients. There are larger-than-life shots of sesame seeds, bonito flakes, shiso leaves, the adzuki beans used to make the mame daifuku filling, and even a special kind of premium rice that sells for $50 a pound.

“I like to literally focus on food, to look at food in microscopic detail, and to show the beauty that’s there that most people don’t even see,” he said, pointing out the different pink and yellow colors that magically emerge when you zoom in on a seemingly black sheet of nori seaweed.

“It turns out shiso leaf is also really beautiful,” Myhrvold added. “The architecture of the leaf has these veins that branch out. But there’s also these little droplets on the underside of the leaves that actually contain the flavor oil that makes shiso what it is, and they look like clear resin and little bits of the jewel amber.”

Nathan Myhrvold, Shiso. Photo by Nathan Myhrvold/Modernist Cuisine Gallery LLC

In the exhibition, these magnified images are displayed on a monumental scale, printed on archival paper. The result is something more akin to abstract art, with an intriguing, alien-like beauty totally absent from photographs one might take of their brunch order to share on Instagram.

The celebration of these ingredients is amplified when paired with Odo’s cooking, which is about as delicious as you would expect coming out of a two-Michelin-star kitchen. I went to the space to experience both the art and the food, and ordered the tasting menu.

Courses included a jewel box-like tray of sushi, a trio of delicately breaded and fried kushi-age skewers, and an ingenious shabu shabu, in which the guest cooks mushrooms and thin slices of beef themselves in a delicious broth heated over a flame in what appears to be a coffee filter. Any one of the dishes would have been worthy of appearing alongside the art on the gallery walls.

Nathan Myhrvold, Adzuki. Photo by Nathan Myhrvold/Modernist Cuisine Gallery LLC.

Myhrvold has been a photographer since childhood, and spent years in the darkroom developing large format film—especially as his day job at Microsoft allowed him to afford more expensive cameras and equipment. And while he was at the tech giant, Myhrvold took a leave of absence to study at culinary school in France. It was an experience that presaged his next act, as an acclaimed cookbook author, focusing on what’s popularly known as molecular gastronomy.

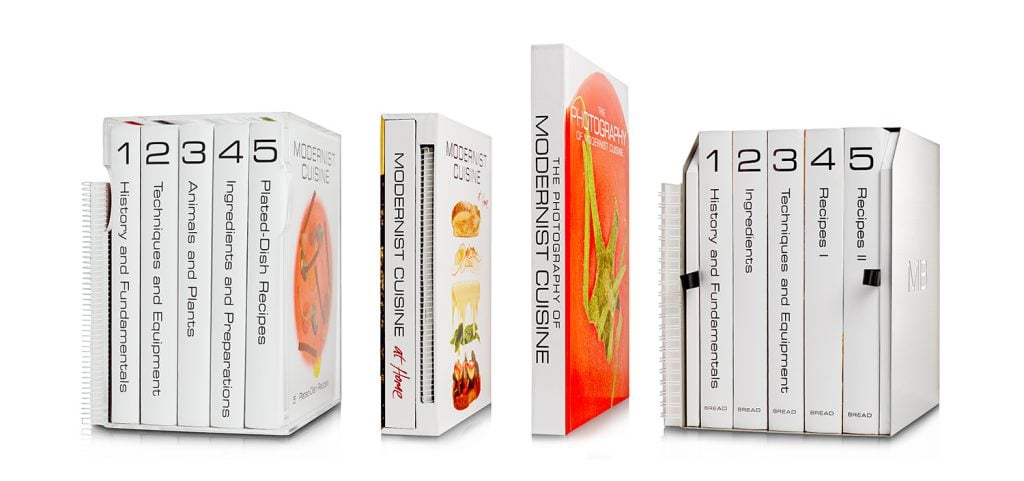

In 2005, he began working on the six-volume, 2,400-page opus that became Modernist Cuisine: The Art and Science of Cooking (2011). It won the 2012 James Beard Foundation’s Cookbook of the Year award. Modernist Bread followed in 2017, and Modernist Pizza in 2021. (Next up will be a book on pastry.)

The Modernist Cuisine books. Photo courtesy of the Cooking Lab, LLC.

For each book, Myhrvold not only meticulously tested a multitude of different cutting-edge cooking techniques and the science behind them, but photographed every step of the way. That led to two books specifically focused on his art: Photography of Modernist Cuisine (2013) and Food & Drink: Modernist Cuisine Photography (2023).

Those stunning images seemed almost magical in their ability to capture the act of cooking in gorgeous detail. Many feature appliances and cookware sliced in half to present a unique cross section view. All were shot with custom-built cameras.

A photo of broccoli from Modernist Cuisine: The Art and Science of Cooking (2011). Photo by Nathan Myhrvold, courtesy of the Cooking Lab.

“I build all of the equipment, and to me that is a way of both increasing the technical quality of the photos, but also it’s my homage to the discipline,” Myhrvold said.

Super high shutter speeds and specially-designed robotic rigs allowed him to capture fleeting moments—like sabering open a champagne bottle or spilling a glass of wine—in ultra crisp, high-resolution images.

A photo of wine spilling from Food & Drink: Modernist Cuisine Photography (2023). Photo by Nathan Myhrvold, courtesy of the Cooking Lab.

“We’re only just now getting very fast shutter speeds with the latest set of digital cameras—for a long time, the fastest would be a thousandth of a second. And that’s way too slow. You get a blur. So my flashes are 160 thousandths of a second,” Myhrvold said.

“We all spill wine. But it happens so fast you can’t realize how beautiful it is when it occurs. It looks like some crazy glass sculpture from Murano in Venice or from Dale Chihuly or something,” he added. ”It’s amazing-looking, but with our normal human senses we can’t see it. So these photos are a way in which I can show you a vision of food you haven’t seen before.”

Installation view of “Nathan Myhrvold: Intention and Detail” in the lounge space at the Gallery by Odo, New York. Photo by Olive Mirra/Modernist Cuisine Gallery LLC.

Achieving such images—a selection of which are on view in the Odo lounge space—is not without its potential downsides, Myhrvold warned: “When you do these splash shots, you wind up just getting soaked in wine. When you drive home, you better not get stopped by the cops, because they’re going think you’re drunk no matter what you say, because you just reek!”

But while the process might be messy, the results are so beautiful that fans of the cookbooks soon began inquiring about whether prints were for sale. (Myhrvold’s new series of 10 large-format artist proofs is priced at $17,500 each, as is the full set of 12 mame daifuku photos.)

Nathan Myhrvold, Kuromai. A photo of black “Forbidden Rice” taken under a microscope. Photo by Nathan Myhrvold/Modernist Cuisine Gallery LLC.

After his success in self-publishing—the book no publisher dared to take a chance on went on to sell 300,000 copies, despite a $600 price tag—Myhrvold saw no reason not to open his own art gallery as well.

Today, the Modernist Cuisine Gallery has spaces in New Orleans and La Jolla, San Diego, and is looking to expand to Miami. (Outposts in Las Vegas and Myhrvold’s hometown of Seattle have since shuttered.) But the New York show should help bridge the gap between art, science, and the culinary world for an artist, scientist, and chef whose work does just that.

“Nathan Myhrvold: Intention and Detail” is on view at the Gallery by Odo, 17 West 20th Street, New York, New York, September 24–November 3, 2024.