Last summer, the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened an exhibition to showcase one of its splashiest new acquisitions: a golden coffin from the 1st century BC dedicated to Nedjemankh, a high-ranking priest of the god Heryshef of Herakleopolis. But the show shuttered two months early when the museum discovered that the coffin—which it had purchased for nearly $4 million in 2017—had in fact been looted from Egypt.

Yesterday, that coffin was formally returned to its country of origin in a repatriation ceremony in downtown Manhattan. In the presence of numerous Egyptian officials including Sameh Hassan Shoukry, the minister of foreign affairs, New York’s district attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. provided more detail about the object’s shadowy journey from the Middle East to the United States and acknowledged an ongoing international investigation into those responsible and larger problems that persist in the battle against international trafficking of stolen antiquities.

“Our office has been investigating this for more than seven years with support from our law enforcement colleagues in Egypt, Germany, and France,” Vance said. The coffin’s return is part of a concerted push by the DA to recover stolen cultural treasures and return them to their countries of origin. Hundreds of possibly looted objects from around the world are currently under investigation, according to Vance.

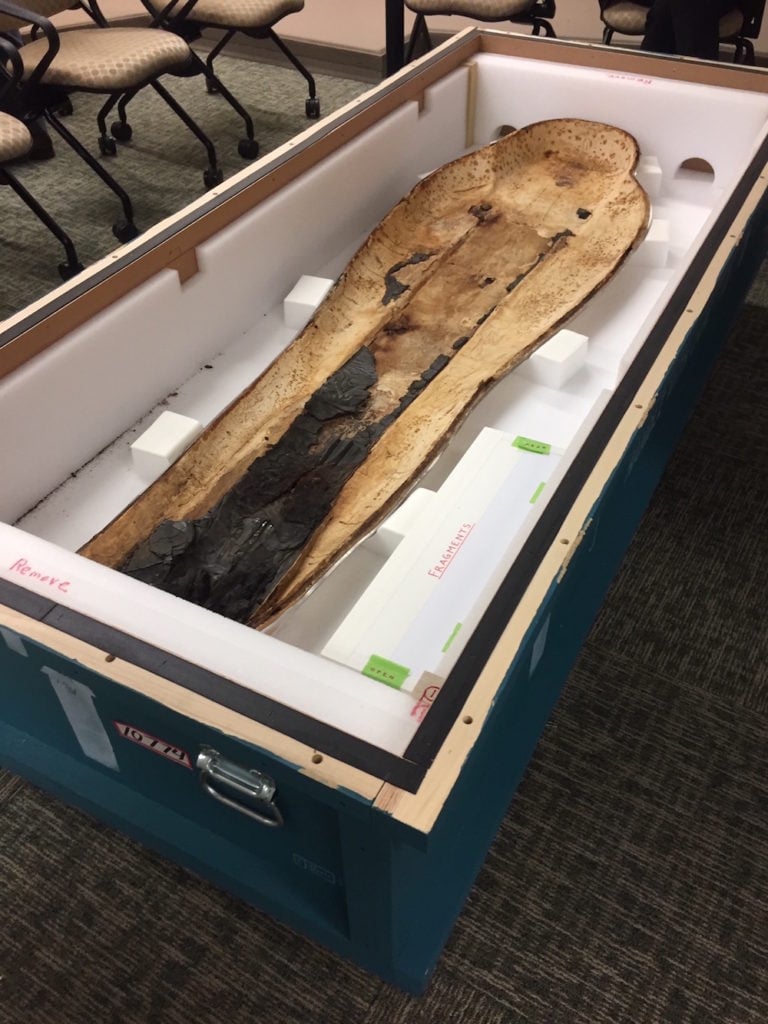

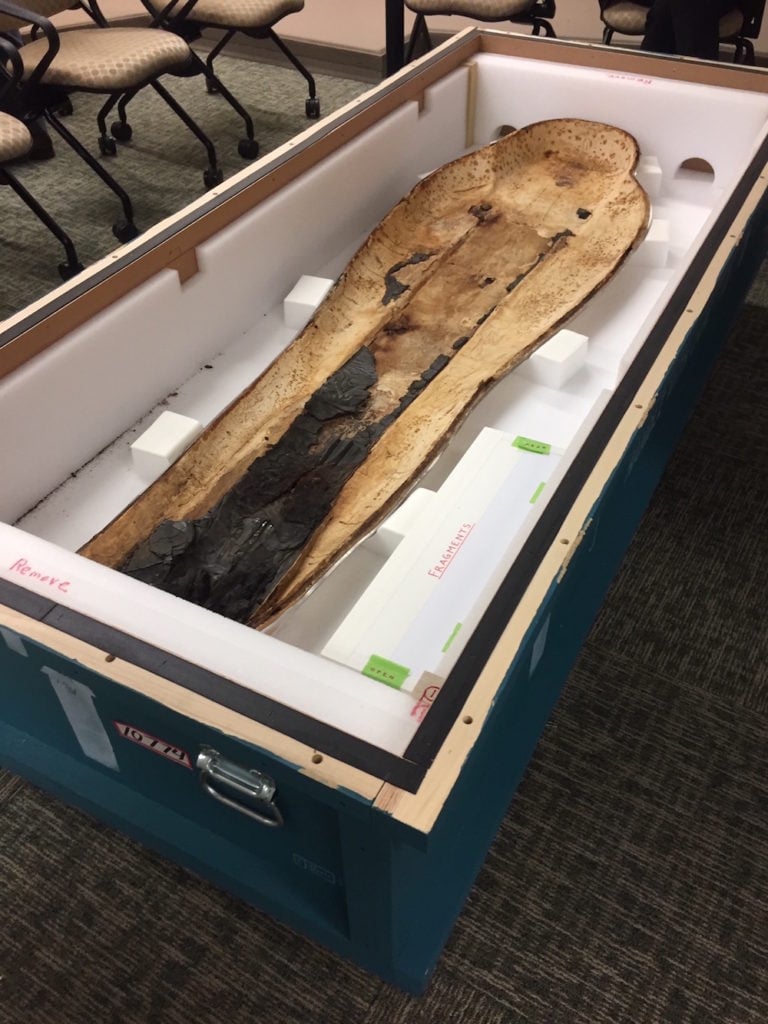

The coffin purchased by the Met was crafted in Egypt sometime between 150 and 50 BC and remained buried for more than 2,000 years. It was stolen from the Minya region of Egypt at the end of the revolution in October 2011, smuggled out of Egypt, and illegally transported to a warehouse in Dubai, according to law enforcement. It was later shipped to Germany for restoration and then sent to France, where it was sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for nearly $4 million by an art dealer.

Some details, including pending criminal charges for those involved, have not yet been determined or could not be discussed because of the ongoing investigation, officials said. The Met previously stated that it had received a false ownership history and fake documentation for the coffin, including a forged 1971 Egyptian export license. The DA’s office seized the object from the museum in February. Once presented with evidence of the theft, the Met “fully cooperated,” according to the DA.

Photo by Eileen Kinsella

At the ceremony, Vance suggested the Met should have known something was amiss: There were several “red flags,” he said, like the fact that the six-foot-long, 2,000-year-old artifact had not been part of a documented portfolio before it arrived in Paris. “It is the responsibility of a buyer to confirm the proper provenance of a piece of art or antiquity,” Peter Fitzhugh, a special agent-in-charge for Homeland Security, said.

Back when the coffin was seized from the Met—the most recent of several incidents in which the museum surrendered objects that appeared to have been stolen—the museum said it planned to review its acquisition procedures. The Met did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the purchase of the coffin or the status of that review. But in a podcast interview with In Other Words posted today, the Met’s director Max Hollein offered some additional insight into his perspective on restitution.

Hollein emphasized that the Met wants nothing to do with stolen objects and is proactively researching objects with questionable provenance. “It is clear for the Met—especially for the Met—anything that came to the Met, for whatever reason, in an unlawful context, that we should restitute that work,” he said.

But he fell short of endorsing the more progressive views put forth by France and some other European countries. He does not share the view expressed by the Élysée Palace, which announced in 2017 that “African heritage can no longer be the prisoner of European museums.”

“I see the conversation currently, in some areas, going into a direction that basically almost makes the argument that an object or any artwork ideally should be returned to its original… place of origin,” Hollein said. “[T]o argue that works can really only fulfill their destiny by returning them to the place where they originated, I think that goes completely against the whole idea, of… well, for sure, the encyclopedic museum, but actually, also the idea of art having, that has been traveled, has been traveling around the world, and influences, and is in dialogue with so many different people.”