People

‘What I Do Is Also a Form of Religion’: Inside the Obscure and Tantalizing World of South African Artist Nicholas Hlobo

We visited the artist's studio in a converted ex-synagogue in Johannesburg.

We visited the artist's studio in a converted ex-synagogue in Johannesburg.

Emmanuel Balogun

South African artist Nicholas Hlobo laces themes of intimacy, conflict, and obscurity deep into the textures of his work.

To get to the root of the work he is making, a visit to his studio felt apt—a defunct synagogue in a multi-ethnic neighborhood of Johannesburg, where he conceives his multimedia work that spans painting, weaving, sculpture, installation, and performance.

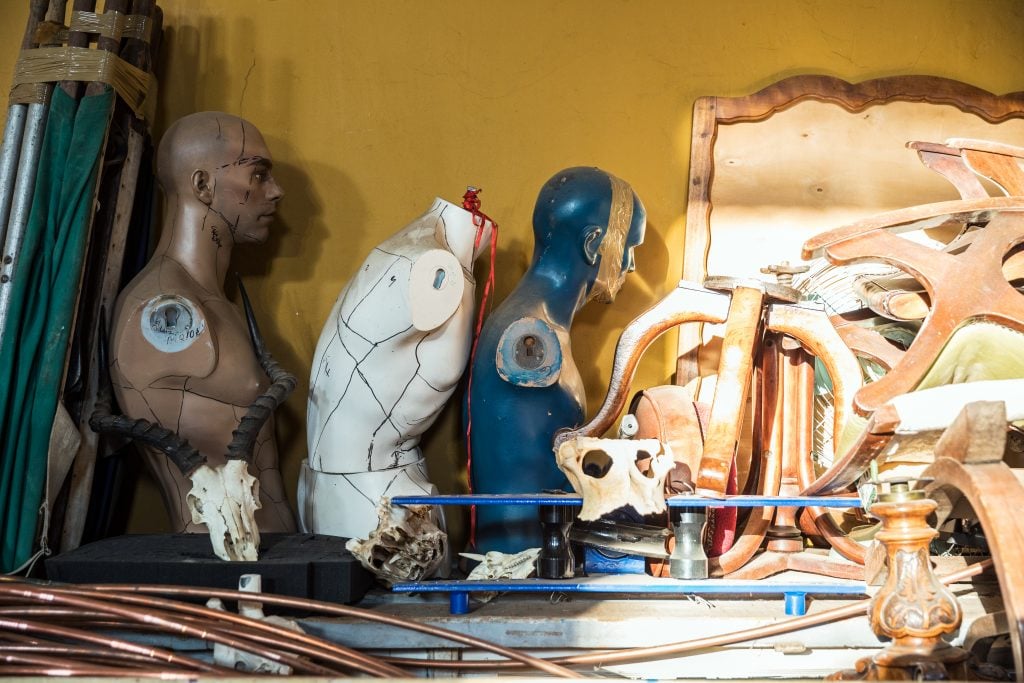

Through embellishing and re-constructing used objects such as leather costumes, mannequins, and rubber inner tubes from car tyres—severed, hung or laid—the artist “re-socializes” materials with meaning. By reworking mundane or masculine wares such as leather or car parts into dicks or fetishistic boots and loot, the artist both instructs the onlooker, and accuses them, of seeking out the erotic.

Hlobo’s loaded artistic creations elicit compound readings, with mysteries still left to unpack. Indecipherable forms recall conjugal roles or mating rituals, and aliens, ancient, or amphibious critters stitch together private puzzles concerning relationships, religions, or romance. These anthropomorphous creeps or demigods without eyes nor mouths spark queries into the artist’s own life as a gay Black man born among Apartheid’s oppressive regime. While South Africa is ahead of the curve compared to other nations in Africa that remain wedded to homophobic laws and litany—it is a country where queer communities are regarded as relatively free—for some it is safer to live with their sex in the shadows. But Hlobo insists his sexuality causes him no conflict nor pain.

Vibrant, chatty and high-spirited, Hlobo is welcoming into his world, a gated expanse. His studio is surrounded by a surrealist oasis replete with an elaborate pond, birds whose elongated beaks rest on curving trees or emerge from bushes of flowers, and fruits that line the garden, growing in abundance.

As I enter Hlobo’s sanctuary, the first studio he has ever owned, a cast iron sign asserts boldly: “COLORED ONLY, No Whites Allowed.” The sign is a playful gesture—and a purchase, not Hlobo’s creation. “I always have to find ways of asserting that which is in conflict with me,” the artist told me.

Nicholas Hlobo in his studio, Lorentzville, Johannesburg, South Africa. Photo by Ilan Godfrey.

Hlobo rocketed to art world fame after his monumental rubber and ribbon sculpture-come-curiosity Limpundulu Zonke Ziyandilandela / The Encyclopedic Palace captivated art enthusiasts walking through the Arsenale at the Venice Biennale in 2011. Since then, he has participated in several key exhibitions and biennials across the globe. However, esoteric truths live within his works, which can sometimes give the impression of an artist conversing with himself about his country’s past and present. While his creations travel far and wide, he adamantly keeps close to his culture by working with titles written in the Xhosa language.

These artistic gestures are not intended as acts of exclusion nor restitution—just like the sign on his studio, which is a jibe in his local context. The words of the late South African-born but exiled writer, Lewis Nkosi, could explain Hlobo’s temperament: “for a Black man to live in South Africa in the second half of the 20th century and at the same time preserve his sanity, he requires an enormous sense of humour and a surrealistic kind of wit.”

Hlobo’s surreal synagogue-turned-studio in Lorentzville, a former Jewish working-class neighborhood that is now multi-ethnic, supports his artist view: “What I do is also a form of religion,” he said. The space is occupied with artifacts with either devout or artistic sensibilities: ranging from a menorah, to skulls and bones. Religious gnomes line the walls but everything has its place, whether it is piles of coiled copper wire, maps of forgotten territories on designated walls or mannequins hiding in stairwells.

Searching the space, I encountered an archive work by the artist, a black rubber oddity lying curled in the basement; when unfurled, it was a large human body-sized shape marked with Hlobo’s signature stitching. Items that were once part of long-dismantled sets, and intermingling new and old objects abound—all the part and puzzle of African existence that Hlobo unfolds into the gallery’s white cube.

Nicholas Hlobo’s studio, Lorentzville, Johannesburg, South Africa. Photo by Ilan Godfrey.

When I asked what led him to become an artist, he looked back to life before art, when he worked in construction. “We were discouraged from being active in politics,” the artist said, referencing the many other Black boys who were made to become men through deprivation and structural violence, living in a segregation era that saw millions of Black folk forcibly resettled by way of white instruction into Black “homelands.”

Speaking of the men that sacrificed their lives for the freedom fight or lost as political prisoners either incarcerated or exiled, he said: “Many from where I am from started disappearing into the struggle—the struggle to deconstruct the Apartheid regime.”

In South Africa, civil liberties, such as education and employment, among other economic opportunities, were restricted from Black people by state decree until the apartheid ended in 1992, by law. The repressive regime’s ways continue crippling generations of communities, in Africa’s most industrialized economy. Talking through the inequality, poverty, social strife, spatial segregation, and rage that persists, Hlobo’s words about how Black communities in South Africa today are faring, referenced crime, lawlessness and those without any choice but to search for help in the street from those who have been spared.

And the artist is determined to build space for where there is need. His work and presence create a system for emerging artists’ aspirations to thrive. Some of these artists work alongside him in the studio. Hlobo asserted that although his country’s standing is “very dire,” he has not left, nor will he entertain ideas to do so.

Nicholas Hlobo in his studio, Lorentzville, Johannesburg, South Africa. Photo by Ilan Godfrey.

We met a matter of days before the opening of “Elizeni Ienkanyiso,” an exhibition of new paintings at London’s Lehmann Maupin gallery (on view through April 23). It’s his first solo outing in the city since his exhibition at Tate Modern in 2008. I saw elements of his signature style of meticulous ribbon work still alive in the artist’s sketches, annotations, and writings.

His thoughts and plans were splattered across studio walls, and the new works I witnessed in progress evinced an evolutionary act of paintwork, with acrylics splattered-brushed-poured in unique, temptingly tactile tracks that symbolize a changing moment in the artist’s process. These voluminous and alluring creations bled colors together, forming kaleidoscopic blues or carnivalesque reds and blacks, and fuse fibers and textures such as leather—a material he has been working with since a seminal visit to a sex museum in Amsterdam many years ago—alongside ribbon.

Reflecting on these canvas paintings Hlobo advances a theory on beauty that has been informed by both his experience and attraction to liminal spaces that exist between what some only see as black or white. “The world in which we exist is beautiful yet so un-beautiful. These concepts of contradiction touch me,” he said. Critical of what he views as a “sanitized” popular understanding of beauty, what Hlobo seeks to do is tell the story of aesthetics “beyond what is idealized or seen on the face,” and carve open space for beauty that envelopes the immaterial, too.

“I go to the struggle to find that which informs that beauty. And that can be very ugly,” he said. “That is where my images come from.” Though his sexuality is out in the open, the artist’s layered speech speaks the story of men whose practice is the art of the unsaid—an expected outcome of communities of men made to love behind closed doors.

“Nicholas Hlobo: Elizeni Ienkanyiso” is on view at Lehmann Maupin London through April 23.