Art World

How Star Painter Nicole Eisenman Leveraged a New Solo Show to Pay It Forward, Putting the Spotlight on Her Naughty Friend Keith Boadwee Instead

"This show is about our friendship more than anything else," Eisenman says.

"This show is about our friendship more than anything else," Eisenman says.

Osman Can Yerebakan

In 2000, after seven years without seeing each other, Nicole Eisenman and Keith Boadwee ran into each other in Tompkins Square Park in New York City. A lot had happened since they first met in 1992, when Eisenman was opening her debut solo show at Shoshana Wayne Gallery in Santa Monica. Back then, the two emerging artists immediately clicked, but it was that encounter in the East Village, in a new millennium, that set in motion their intimate, decades-long friendship.

Sitting on a bench, Boadwee opened up about struggles in his career and personal life, and Eisenman listened. Their relationship since then has both matured—they’ve become each other’s cross-country queer confidants—and remained the same: Boadwee initiates a daily text from the West Coast and Eisenman, who is admittedly not the most responsive, usually writes back. Art they’re working on or new songs they’re listening to are common subjects, but these days, their back-and-forth is about the final touches on their new two-person exhibition at the FLAG Art Foundation, which opens December 12.

“I want this to be about Keith,” Eisenman says from her Brooklyn studio during our three-way FaceTime conversation.

Both artists started out three decades ago and both have always shared an interest in bodily functions as a way to illustrate the failures of heteronormative puritanism. But they went on to very separate career paths.

On the West Coast, Boadwee studied with Paul McCarthy and Chris Burden at UCLA and enjoyed a rapid rise to success in the ‘90s before his work fell into obscurity. Meanwhile, on the East Coast, Eisenman, a RISD graduate, showed at the Whitney Biennial in 1995 and went on to international acclaim that never let up. She has since received a MacArthur “Genius” grant, appeared in two more Whitney Biennials and a Venice Biennale, and is a regular fixture on the auction market, where her work can fetch upwards of $600,000.

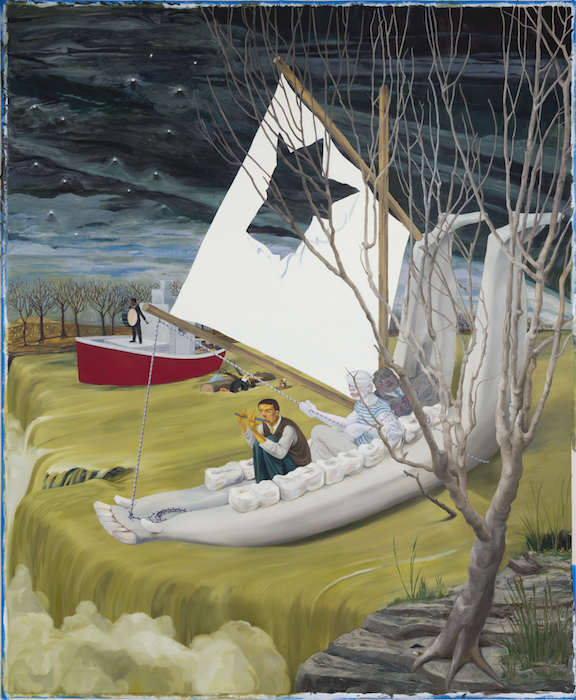

Nicole Eisenman, Heading Down River on the USS J-Bone of an Ass, (2017). Courtesy the Ovitz Family Collection, Los Angeles.

“I believe in Keith’s lifelong project,” Eisenman says about her friend’s commitment to subverting consumerist ideals with in-your-face sexuality and human fluids. Boadwee filters familiar emblems of pop culture and mainstream art history—from Smurfs to Abstract Expressionism—through a subversive directness, comparable to his mentor McCarthy and the Viennese Actionists of the 1960s.

“I never understood the art world’s criteria for who to reward or avoid, but in Keith’s case, it doesn’t make sense,” Eisenman says.

That’s why she is stepping in to make a correction. Last year, the painter won the inaugural Suzanne Deal Booth / FLAG Art Foundation Prize, which came with a $200,000 award and a traveling show, first at the Contemporary Austin and later at FLAG. After opening the show’s first leg, the sculpture-heavy “Sturm und Drang,” in Texas in February, Eisenman realized she could give Boadwee the show he never had.

“This show is about our friendship more than anything else,” Eisenman says.

Today, the 59-year-old artist is probably best known for his performative enema paintings from the ‘90s. The images of Boadwee or his occasional collaborator, artist AA Bronson, squirting paint from their anuses onto canvas still pack a punch as a riff on the Jackson Pollock-style machismo salient in so much American art.

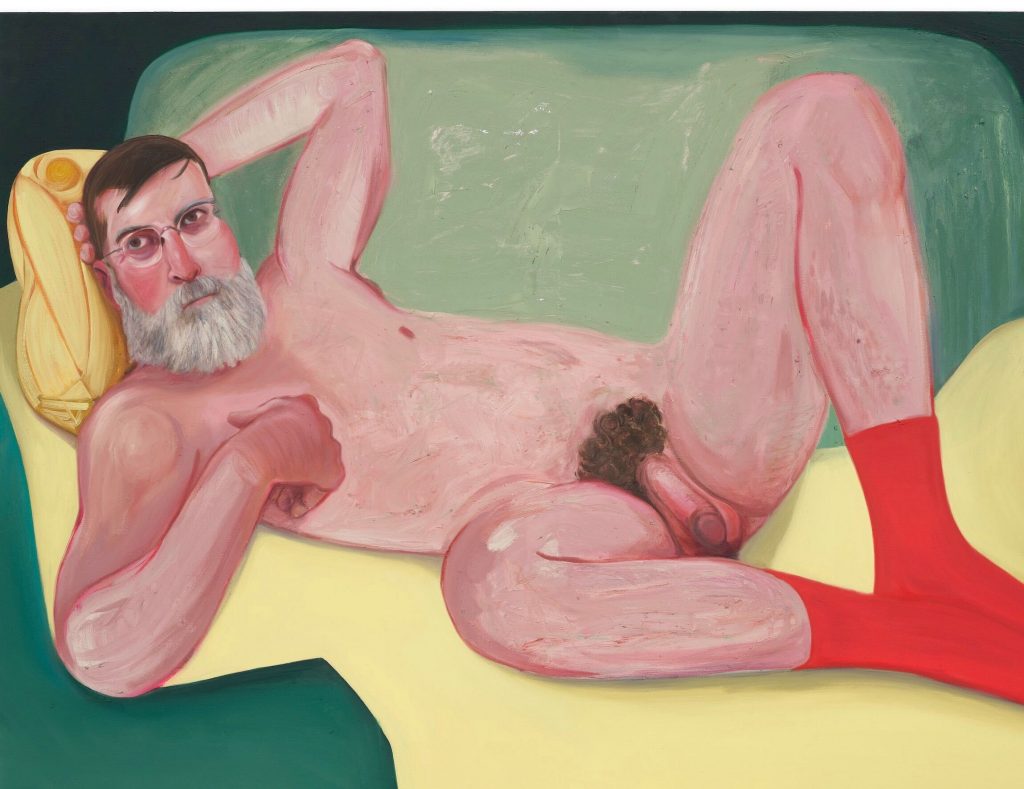

Nicole Eisenman, Keith (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

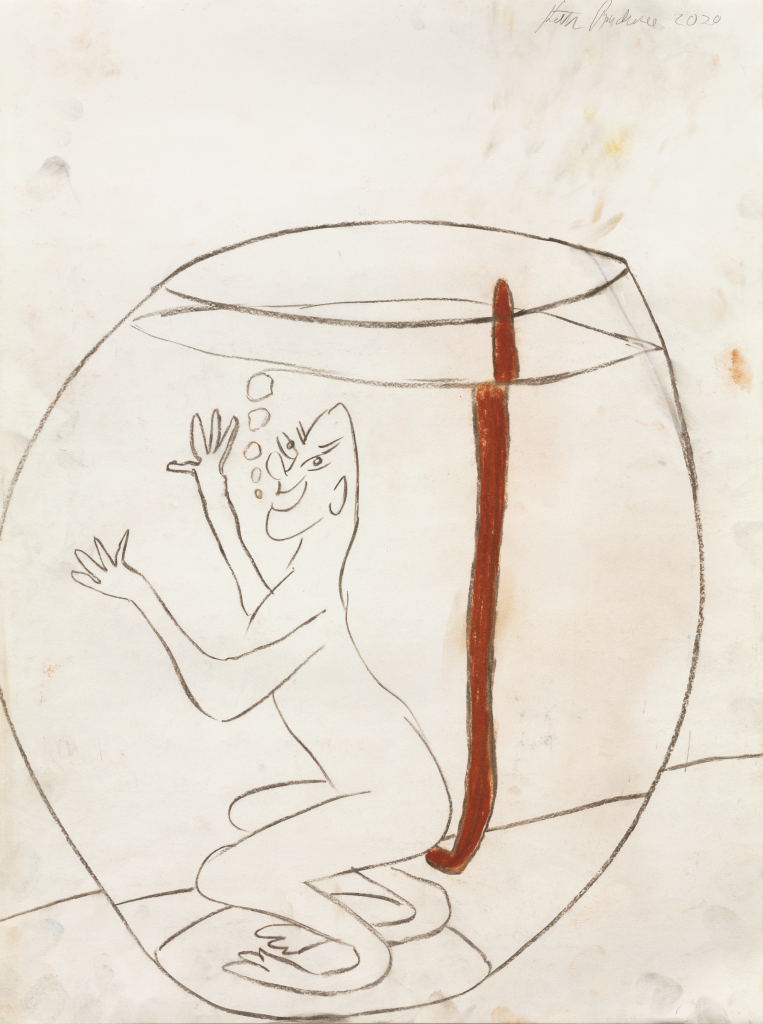

Currently based outside of Oakland, Boadwee continues to paint and draw humorous scatological scenarios in which feces stand in for human flaws and reason is tested by farce.

“Since switching back to drawing from photography 12 years ago, I’ve been in a hyper-production mode,” he says. But he’s worried about not finding his critical and commercial footing in the industry. “As the work piles up, I existentially ask myself, ‘What am I going to do with all of this art?’”

Eisenman identifies a certain sterile sensibility in the art world that she thinks kept Boadwee’s unabashed imagery off of museum and gallery walls. Her initial suggestion to FLAG was to give both floors of the show to her friend, but the award’s rules demand the winner’s participation. They found a solution in each taking one floor and weaving together two shows, one of which includes Eisenman’s new painting of a nude Boadwee, titled Keith (2020).

Donning nothing but a pair of red socks, the artist reclines in a pose familiar to art history, but unusual in his gay-bear-daddy body. The painting greets visitors to the joint show about queer liberation, which has been a shared commitment in the duo’s friendship.

Keith Boadwee, various drawings, (2016-19). Courtesy of the artist and The Pit, LA.

“We come from a generation in which, after all that struggle, the reward was the most heteronormative ideal: marriage,” says Eisenman. Boadwee, whose work deals precisely with the normalization and commodification of queerness, agrees.

The artist explains his fascination with feces (which he has depicted as cookies on a baking tray, a smear over a liberty bell, and as a patient on a therapist’s chair) as an homage to Warhol’s non-hierarchical read on Coca-Cola as a unifier of social class—something everyone drinks. “We all have a butthole and shit in the same way regardless of wealth, gender, or anything else,” Boadwee says.

Eisenman considers her friend’s sexual directness to be distinct from hers. “Keith’s work has always been performative and open about the process,” she says. “For me, it’s about the fantasy of bodily functions.”

Eisenman’s oldest work in the show, Charlie the Tuna (1993), shows the StarKist mascot poking a woman’s buttocks with his fin; her most recent, Just do it (Sarah Nicole) (2020), is a depiction of a nude woman in red hues calmly clipping her nails. The body still prevails, but the element of mystery is more evident in the later work.

Keith Boadwee, various drawings, (2016-19). Courtesy of the artist and The Pit, LA.

“I’ve cycled through my psychosexual, violent, and humorous phases, but I’ve made a decision to move away from those,” Eisenman says.

She remembers getting harsh reviews in the ‘90s, particularly from white male critics, for making “juvenile” paintings. “My work was much funnier back then, but at some point, I just didn’t want to be fun anymore.”

The story behind the show’s connective tissue encapsulates why the two artists are not only friends, but also each others’ support systems. When Eisenman needed pictures of a sphincter for the flower paintings in her Hauser & Wirth show in Somerset, Boadwee flew to New York to spread for her.

“After I took photos of Keith’s butthole, he was sitting there in nothing but socks, and he needed to be painted,” she says about the moment she accidentally discovered her friend was the muse for her next show, too.

“She’s telling it wrong!” Boadwee jumps in. “I had only my pants off when she started talking about needing inspiration for paintings in the new show. I pulled the rest of my clothes off and said, ‘Here’s a fucking inspiration.’”

“Nicole Eisenman and Kieth Boadwee” is open at The FLAG Foundation from December 12, 2020 to March 13, 2021.