Art World

With Ingenuity and Strange Beauty, Northern California Artists Rebuild From the Ashes a Year After the Devastating Wildfires

Artists whose homes and studios were destroyed used ashes and rubble to create new work.

Artists whose homes and studios were destroyed used ashes and rubble to create new work.

Sarah Cascone

One year ago, artist Norma I. Quintana’s Napa home burned to the ground, taking with it nearly all of her personal possessions, including her art collection and all of her cameras. Armed only with her iPhone X, Quintana continued working, sifting through the ashes and documenting the charred remains of her home.

“I would dig literally for my memories,” Quintana told artnet News. Working through her own grief forced her to open new doors artistically—she had to shoot digitally, and in color, for the first time. But as she continued to work, “my world as a fine art photographer has opened to the digital world.” She ultimately made 100 photographs from the wreckage.

Those haunting images, beautiful in their destruction, are now the subject of a solo show, “Forage From Fire,” at San Francisco Camera Work (October 4–20, 2018). Quintana lost her home to the Atlas fire on October 8, the day that the fires first began. She and her family fled in the middle of the night as the flames bore down upon them, and were lucky to escape with their lives.

Norma I. Quintana, Typewriter (2017). Photo courtesy of the artist and San Francisco Camera Work.

In some areas of California wine country, the flames were not fully contained until October 27. More than 210,000 acres burned in 250 separate fires, taking the lives of 44 people and causing $14.5 billion in damages. It was the greatest loss of human life due to wildfire since 1918.

Among the many people to reach out to Quintana in the aftermath of the fire was Heather Snider, executive director of SF Camerawork. The gallery is letting the artist keep 100 percent of the proceeds of print sales from the show.

Norma I. Quintana, Forage From Fire #21 (2017). Photo courtesy of the artist and the Sonoma County Valley Museum of Art.

The artist’s exhibition—the photos are also currently on view in two other area group shows—is just one of the many ways in which the Northern California community is commemorating the devastating October 2017 fires, and showing how the region and its artists have banded together to rebuild.

In the process, they also serve as a powerful testament to an artist’s drive to create. Many of those who lost almost everything used the few materials they had left to make new work.

A firefighter combating the Northern California wildfires. Photo courtesy of the Bureau of Land Management.

At least 80 artists in the North Bay lost their homes to fire last October, and 62 lost their studios, according to a study by Northern California Grantmakers. The median estimated financial loss among respondents was $77,500.

One year after losing his home and two art studios in Napa, which collectively held nearly every work he had ever made, Clifford Rainey still hasn’t come to terms with the loss, or even completed an inventory of his work to determine what survives in museums or private collections. “It just stabs you,” he told artnet News.

Although he has benefited from $14,395 raised on a Go Fund Me page, he has not come close to regaining what was lost, and is currently in a class action lawsuit to recover the cost of his equipment and artwork.

Rainey is not alone. Many artists have run into obstacles seeking reimbursement from insurance companies for their lost art. “Due to the complicated insurance process,” notes the California Grantmakers study, “combined with stressful deadlines during an already traumatic time, it was often difficult to take advantage of these potential financial resources in the short window of time offered.”

And like Rainey, many have struggled to return to work in the aftermath. “With the loss of equipment, space, and existing projects that cannot be replaced, many artists share in focus groups that they are struggling to reaffirm their identities as an artist,” notes the study, quoting one participant who shared that “my studio is gone. It vanished. And I don’t know who I am.”

One of Jeff Frost’s photos for California on Fire. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The situation doubtless would have been much worse were it not for the many resources available for artists, ranging from the Federal Individual Disaster Assistance Program and the Federal Disaster Unemployment Assistance benefits through the Employment Development Department to more arts-specific programs such as CERF+ and the Joan Mitchell Foundation’s Emergency Grant Program.

Creative Sonoma also stepped up to the plate, awarding a total of $164,625 in recovery fund grants to 15 individual artists, arts organizations, and creative businesses that experienced economic loss, and 115 that suffered physical loss. (The organization expects to exhaust its available funds by the time applications close at the month’s end.)

“These funds were unrestricted—it was important to ensure that the creative community be able to spend them on whatever their most pressing needs were,” Creative Sonoma director Kristen Madsen told artnet News.

Tawnya Lively, Alicia’s Flatware in the Ashes (2017). Photo courtesy of the artist.

For artists who lost their studios, “it has not been financially feasible to replace lost equipment and materials,” wrote Northern California Grantmakers. “Many artists are turning to the materials they have available.”

Often, that includes the fire-ravaged remains of their life’s possessions and the few objects that withstood the inferno.

Karen Lynn Ingalls, for example, began adding ashes to her acrylic paintings after the fire, while Tawnya Liveley launched the Firestorm Mosaic Project. She takes broken shards of porcelain and charred silverware recovered from burned houses and transforms them into mosaics that she hopes can become new heirlooms, bringing beauty into a difficult chapter in a family history.

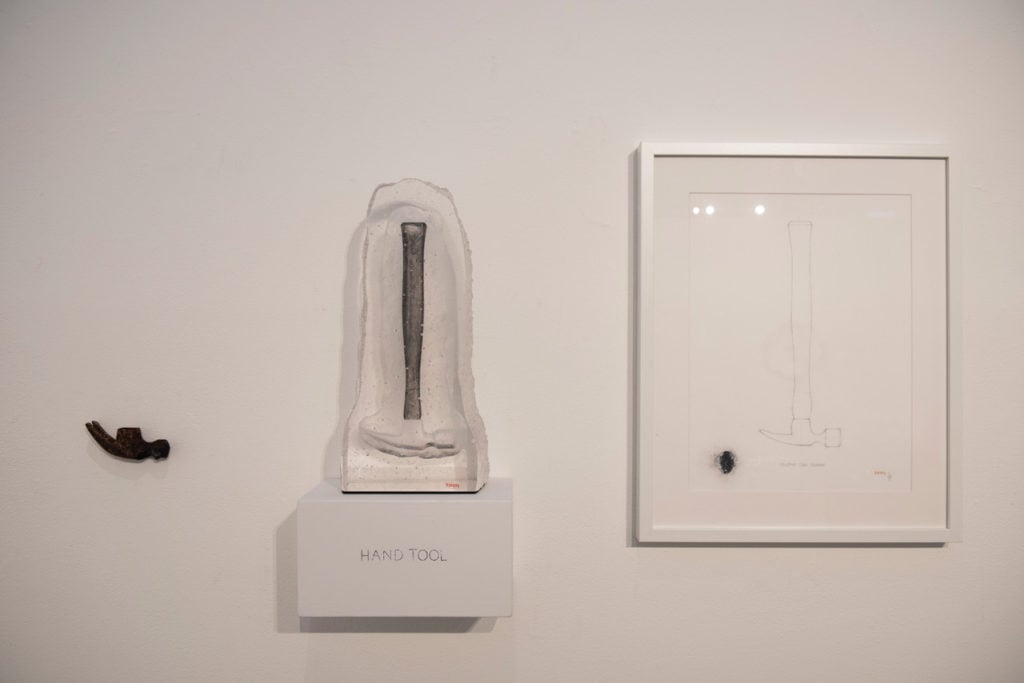

Clifford Rainey, Benicia Hammer, from the “Hand Tools” series. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Clifford Rainey, meanwhile, began collecting burned charcoal from around his property and using it to make expressionistic drawings. “It took a few months to realize they were pretty terrible, but at least it got me moving,” Rainey said.

More recently, he’s begun a series called “Hand Tools,” based on the burned remains of implements he’s recovered from the rubble. He’s cast the imprint of these objects into molten glass, recreating the outline of the destroyed portions in pencil drawings and rubbing some of the ashes in the mold.

“They’ve like a ghost image,” said Rainey, who will debut the works at SOFA Chicago in November. “A little memory of the things that don’t exist anymore.”

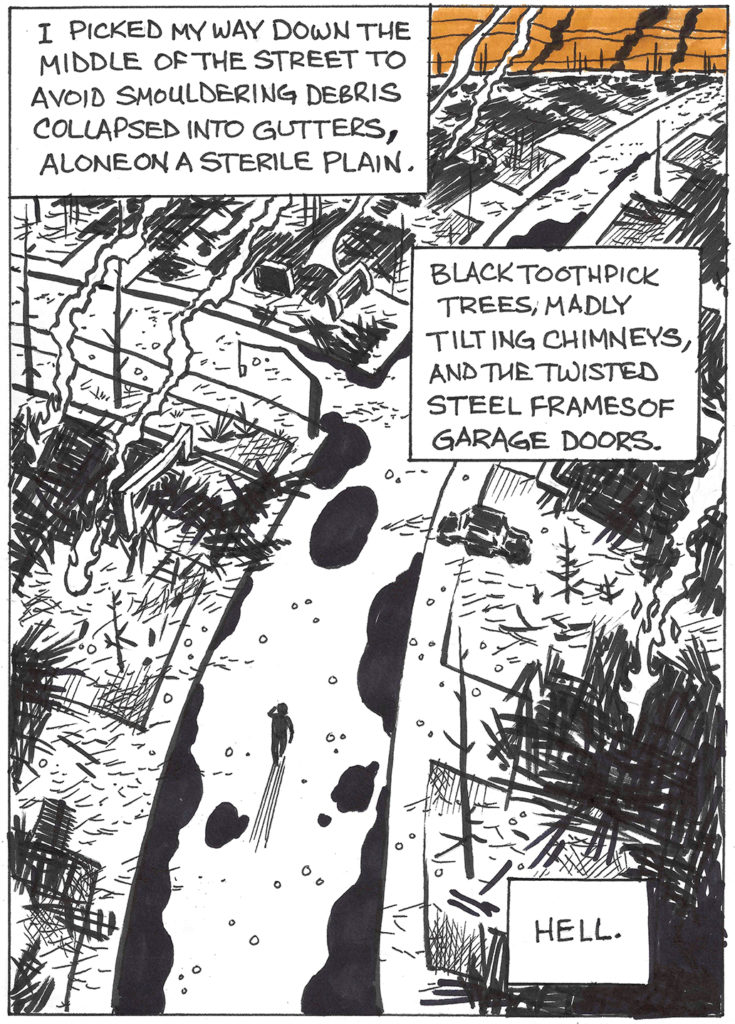

Other artists have simply channeled their grief into new work. After the graphic novelist Brian Fies‘s Santa Rosa home burned to the ground, taking with it everything he owned, he drafted an 18-page graphic novel describing his flight ahead of the fire, his return to his ruined house, and the immediate aftermath. The story went viral, reaching over three million people.

Brian Fies, A Fire Story, page 10. Courtesy of Brian Fies.

The pages from the original comic are currently scattered across Northern California in six group shows responding to the fire at venues including the Sonoma Valley Museum of Art and First Street Napa Gallery. In March, Abrams ComicArts will release an expanded version of A Fire Story, now featuring the stories of Fies’s neighbors and others in the community, as well as the artist’s environmental insights about the fires.

“I don’t know if any single artist can encompass the enormity of a disaster like ours, but I think several artists coming at it from many different angles can convey a very good sense of the event,” said Fies. “Words, drawing, photographs, paintings, sculptures, textiles, found objects, and artifacts—each provides a little window that I think gets close to a complete picture.”

Tawnya Lively, Alicia’s Flatware (2017). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Many institutions’ staff members and patrons were among those who lost their homes, and many art organizations came close to ruin themselves. Located within the evacuation zone, some institutions and landmarks were forced to close for weeks following the widespread blazes.

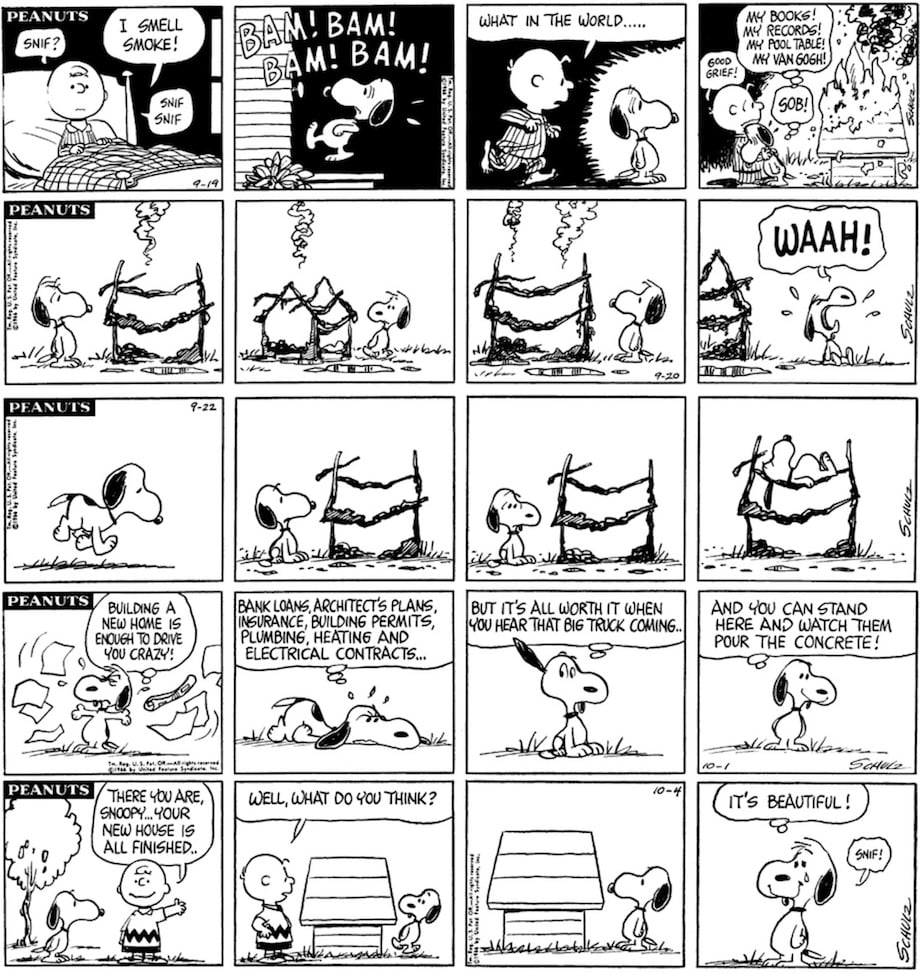

The home of the late “Peanuts” creator Charles M. Schulz—where his wife, Jean Schulz still lived—sustained some of the worst damage. It burned down, and with it, some of Schulz’s original artwork. (A similar misfortune befell the artist back in 1966, when his art studio burned to the ground. To commemorate it, Schulz channeled his loss into his comic strip, dedicating two weeks to a story line in which Snoopy’s doghouse is burned to the ground.)

Charles Schulz drew this Peanuts comic strip in which Snoopy loses his dog house to fire after the artist’s home burned down in 1966. Courtesy of the artist.

But even for organizations that experienced no physical damage, there have been negative financial effects. Fire-related closings forced organizations to delay or cancel programming, which led to reduced opportunities for income—and fewer funds for future programming. And donors who could help buoy organizations during this difficult time may have exhausted their financial means giving to fire relief.

Northern California Grantmakers reports that the 38 arts organizations that responded to its survey reported a median financial loss of $15,000. “It will be a three-to-five year process for everyone,” wrote one responding organization. “We won’t have recovery soon.”

One of Jeff Frost’s photos for California on Fire. Photo courtesy of the artist.

For artists who document natural disasters, the Northern California fire has been a violent crescendo to a steadily rising danger. “I think it’s 15 of the 20 biggest and 15 of the 20 most destructive fires in California history that have happened since the year 2000,” said Jeff Frost, a filmmaker who has chased some 70 fires since coming across a wildfire by chance in 2014.

His forthcoming film, California on Fire, offers a harrowing look the the devastating effects of wildfire, which he sees as the real-time effect of climate change. He says that he wasn’t surprised by the recently published findings of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which indicate that the phenomenon’s deadly effects will soon become irreversible.

One of Jeff Frost’s photos for California on Fire. Photo courtesy of the artist.

In fact, the fires have been coming so fast and so furious that Frost and other artists like him have had to delay major projects because there are no longer enough breaks in between disasters.

For the past two years, Frost has been trying to finish the piece, only to answer the siren call of another fire, heading out in search of new footage. “I keep saying I’m not going to fire chase anymore,” Frost admitted. (The film will finally make its debut at the Napa Valley Opera House on December 9, as part of the programming for the exhibition “Art Responds,” an exhibition of work responding to the fires by 13 artists and filmmakers.)

Stuart Palley: The Atlas Fire burns in Napa and Solano Counties Monday evening October 10th, 2017. The fire was 3% contained and had burned 25,000 acres. Photo courtesy of Stuart Palley.

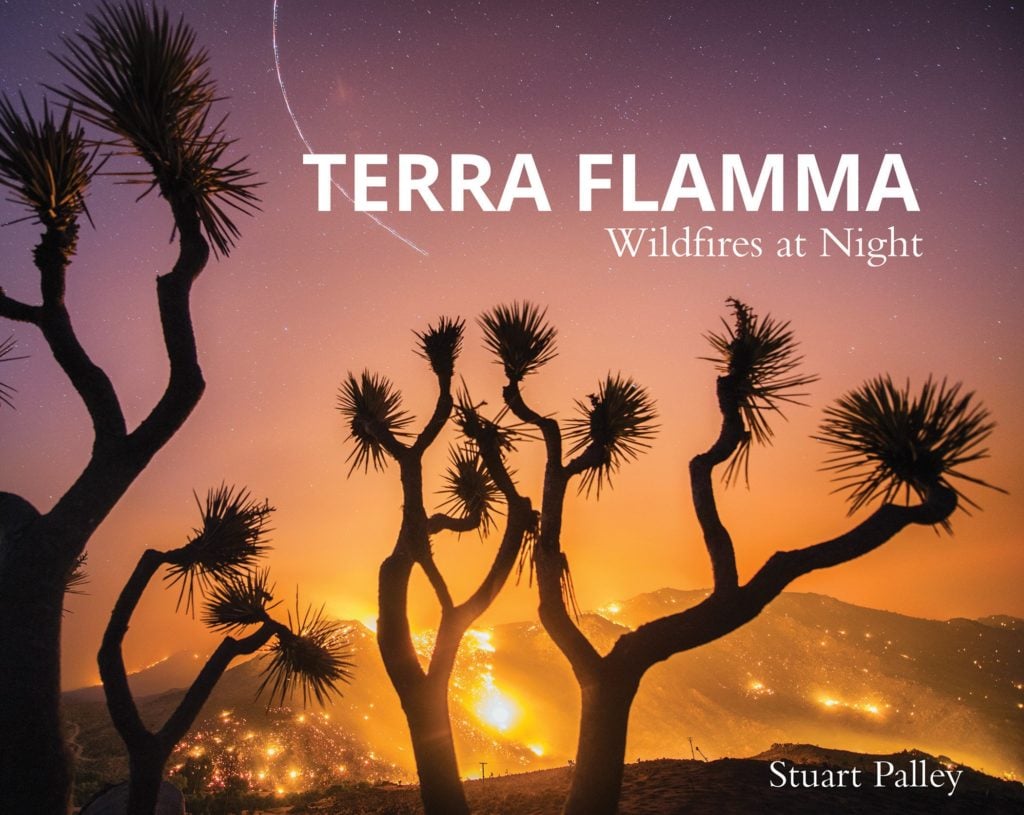

Similarly, publication of photographer Stuart Palley’s book, Terra Flamma: Wildfires at Night, was delayed until August in order to incorporate photos from the wine country fires and then Southern California’s Thomas Fire, which took place in December. (His first solo exhibition, of the same name, was on view at the Santora building in Santa Ana through October 2).

Palley has been photographing California wildfires since 2012, and has probably seen hundreds of homes burn to the ground. But after five days documenting last year’s fires, he described the the devastation wrought upon the area as “a tragedy unlike anything I’ve seen in my career” in an email to artnet News.

“On one hand, fire has natural beauty. It’s this powerful natural force that creates its own light source, so it’s very beautiful, especially being photographed,” Palley added. “But it also has the power to destroy. Fire can kill people and wreck their lives. That negative aspect of fire is never lost on me.”

Stuart Palley’s new book, Terra Flamma: Wildfires at Night.Photo courtesy of Schiffer Publishing, Ltd.

He hopes the book will raise awareness of how wildfires are becoming more deadly, fueled both by climate change and increasing human development in areas vulnerable to catching fire. “I want these photos to combine journalism and art to tell a story,” Palley said.

This past weekend, in an effort to avoid a repeat of last year’s inferno, the Pacific Gas and Electric Company preemptively turned off the power to some 70,000 customers in Northern California’s Sierra Foothills, and an additional 17,000 North Bay residents in Lake, Napa, and Sonoma Counties. According to the New York Times, high winds mean conditions are ripe for another deadly blaze.