The contrast in the painting could hardly be starker.

The pauper, hat in hand, is begging for alms as a stylishly dressed woman visits a grave with an entourage of eight. Beside her, four people, perhaps the Evangelists, intercede for the dead while two robed figures seem to eye the shoe-less beggar disapprovingly.

The 17th-century work, Dirck van Delen’s Interior of a Church, on view at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Florida, is a microcosm of the museum’s complex position—and it echoes some of the assumptions outsiders may make about the institution, which is adjacent to the nation’s third-richest zip code, with an average income of $1.25 million.

On February 9, following a $110 million capital campaign, the museum reopened with a redesign by Foster + Partners, which brings 12,000 square feet of new galleries and a 37,200-square-foot sculpture garden.

The new facade of the Norton Museum of Art, designed by Foster + Partners. Image courtesy of Foster + Partners (2018).

In a sense, the redesign may be judged by its new entrance. Before the expansion, the museum’s front door faced east, a nod to Palm Beach’s seasonal residents. Among those residents is President Donald Trump, whose Mar-a-Lago resort is less than three miles south. He is one of a rarefied group: 40 people with Palm Beach ties appear on the Forbes billionaire list.

But with the new, west-facing front entrance—which looks toward the Dixie Highway, and which is marked by an 80-year-old, 65-foot-tall banyan tree and Claes Oldenburg’s Typewriter Eraser, Scale X—the Norton hopes to present itself as an institution that caters to more than just tony art lovers.

“The west is where we are looking,” said Tim Wride, the Norton’s photography curator. “You have lots of audiences. You just have to make sure they’re welcome.”

An 80-year-old, 65-foot-tall banyan tree at the museum’s new entrance.

New Visitors, New Artworks, New Architecture

The reopening comes as Hope Alswang, the Norton’s executive director and CEO of nine years, retires and is replaced by Elliot Bostwick Davis, who ran of the art of the Americas department at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston for 18 years.

Davis will have big shoes to fill. Alswang was a “pretty fearless director,” said Wride, who curated “The Summer of ’68: Photographing the Black Panthers” in 2015. “That wasn’t what you would expect here,” he said, noting that he came to the Norton from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “I can do more things here than I could do there.”

Outside the museum, along the city’s beachfront, at least a dozen entrances to the water are blocked with signs stating “private” or “no trespassing.” But at the Norton, standing in front of a Soundsuit by NIck Cave, Alswang proudly noted her achievements in democratizing the museum. The collection, she says, grew by 25 percent during her tenure, with works by women accounting for about half of the new additions. A “large number” of the works are by artists of color, she said, adding that the Norton has welcomed more children and minority visitors of late.

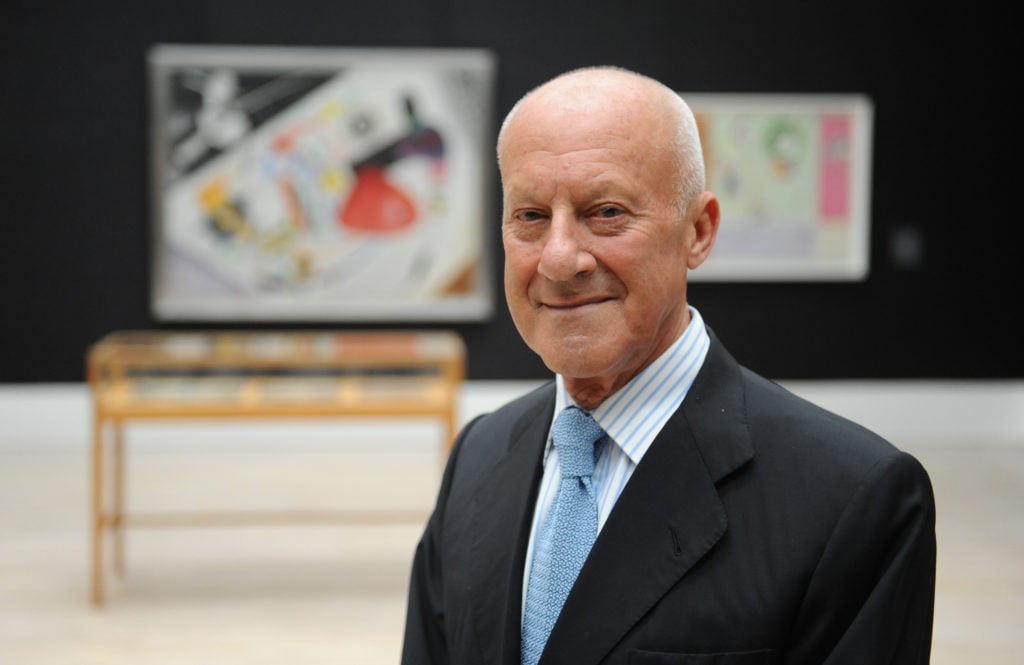

Gilbert Maurer in front of Alfred Maurer’s Still Life with Breton Pottery (ca. 1910), a promised gift of Gilbert Maurer to the museum. Photo: Menachem Wecker.

So changes seem to be afoot in Palm Beach—and change is exactly the focus of Gilbert Maurer’s vision for the Norton. The museum trustee (and former chief operating officer at Hearst) brokered the connection between the Norton Museum and Foster, having worked with the British architect on the Hearst Tower in New York.

“Every institution and nation has a creation myth,” Alswang said. “I was sitting with Gil in his office. He said, ‘If you could have any architect do your masterplan, who would it be?’ And I said, ‘Norman Foster,’ because I was being a smarty-pants. He said to me, ‘Fine. I’m going to call him.’ I had no idea that the Foster + Partners has an office in Hearst tower. Literally, minutes later, [project architect] Michael Wurzel arrived, and the planning started.”

In an interview with Maurer at the museum—part of which took place in front of a 1910 painting by his second cousin, which the trustee has promised to the museum—Maurer noted that Florida, the nation’s third-largest state, is growing by 1,000 people a day. By 2040, half of the US population will live in eight states, with Florida still in the top three most populous states, Maurer predicted.

“It needs everything,” he said. “It needs roads. It needs schools. And traditionally, of course, the older states like New York, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania have [had] 200 years to build their cultural institutions. Here, we are [forced] to develop cultural institutions on a private level almost overnight.”

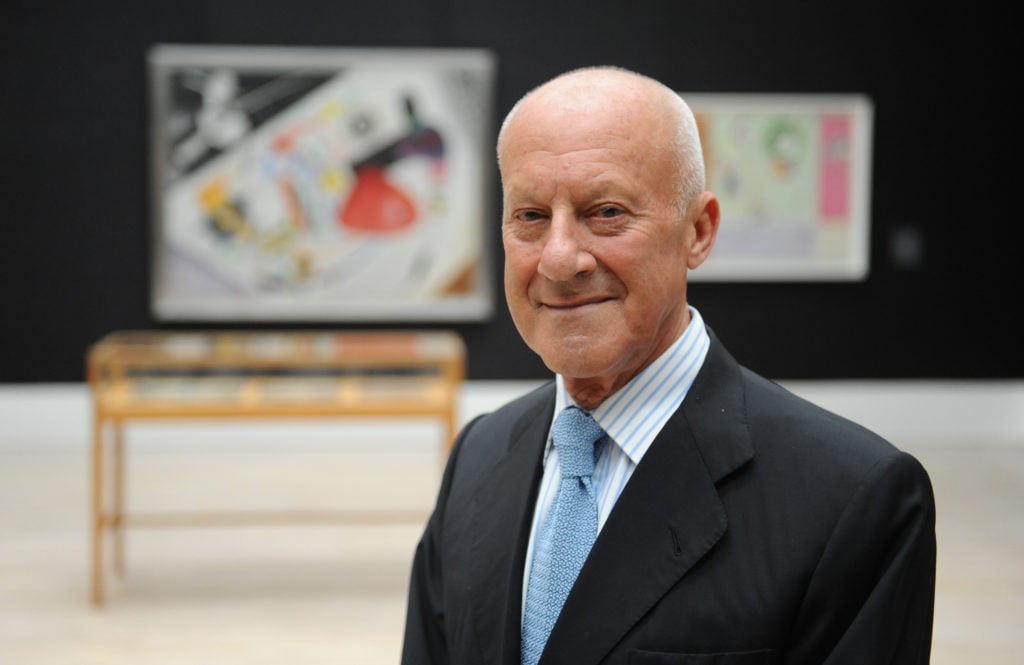

Sir Norman Foster in Munich, Germany. Photo by Andreas Gebert/picture alliance / Getty Images.

The visions of many Floridians are too small, he says. As the state transforms its tourist-based economy to one focused on people who live and work in the state, residents should understand that it’s not necessary to leave Florida to see art.

But there is still a lot of educational work to be done.

“South Florida doesn’t know what good architecture looks like yet,” he said, adding that he hopes Foster’s building will change that.

A Look at the New Space

The changes to the museum are significant, said sculptor Joel Shapiro, whose works are installed in the new sculpture garden, opposite housing for artists-in-residence.

“At first you’re shocked,” he said upon learning that the museum would reinstall his work for the expansion. “It just means you’re going to have to work again, or think again, so you have to re-position it.”

He was delighted, however, about the decision to redesign the old facade, which he felt was problematic. His sculptures were previously installed in two niches at the front of the building, which, as he remembered, had previously held potted palm trees.

“This is an infinitely better plan than they had before,” he said. “It looked like they just stuck on something. It was weird. It was very postmodern.”

Interior view of the Norton Museum’s new galleries. Photo: Menachem Wecker.

The new interior, which can strike one as odd at times, is nevertheless conducive to exhibiting art. The floorplan feels monastic, with cloisters surrounding a garth, which even has a fountain, evoking medieval monasteries.

Side “chapel” galleries allow for the kind of contemplative experience that comes from entering and exiting a space through the same door, rather than branching off. Many of the galleries, at least on the ground floor, are dramatically lit. And from the start, it’s clear that the Norton hangs works lower to the ground than do most museums.

“We think this is a comfortable way for people to view” the work, Alswang said, noting that it’s conducive to young visitors and those in wheelchairs. Foster added that hanging works low creates a “nice intimacy.”

A Wide-Ranging Collection

With the expansion, the museum can present more of its broad holdings.

On the ground floor, there are examples from the Norton’s extensive collection of more than 4,500 photographs, plus paintings by artists including Paul Cézanne, Jackson Pollock, and Hans Hofmann, among others.

Interior Cloister area at the Norton Museum. Photo: Menachem Wecker.

In the Chinese galleries, a 10th century B.C. jade rabbit pendant (“arguably the finest early jade rabbit in existence,” per a label) is among the most tantalizing objects.

And upstairs, sterling examples of medieval and northern Renaissance demand the kind of patience rarely afforded to the contemporary art presented below.

“I don’t want it to be dry, but it does need explaining,” said Robert Evren, the museum’s consulting curator on Old Masters. “Because people are not conversant with the Bible and classical mythology, it can be much harder for them to grasp the meaning of a picture than it was for the educated viewer several hundred years ago. The farther away we get, the more difficult it is to recover the meaning of works.”

In the museum’s new garden—the first Foster has ever designed—there is space to contemplate it all.

“I think it’s a place within a place,” Foster said in an interview. “For me, it would be just significantly better when you don’t see another building. You don’t see a neighbor. You don’t see a road. It’s just nature has taken over.”

View of the “oasis,” Norman Foster’s garden at the Norton Museum. Photo: Menachem Wecker.

With additional space available for future expansion, more changes may be in store for the museum down the road, pending future fundraising.

In the meantime, the new design accommodates, at once, the ladies who come to to the museum to play card games (tables fit four players) and those looking to visit only the bookshop or restaurant without paying for admission.

“It was very clear that there was great potential for a very real transformation,” said Wurzel, the project architect. “There were only a few visitors a day for the galleries. The everyday person wouldn’t go into an art museum.” The new layout, he thinks, will draw more visitors.

For his part, Maurer is already reveling in the new space. “I feel more important when I walk through the door of the place,” he said. “You feel good.”