Art World

How Did a Billion-Dollar Trove of Russian Avant-Garde Art End Up in Uzbekistan?

Discover the best collection of avant-garde art that you’ve never heard of.

Discover the best collection of avant-garde art that you’ve never heard of.

Henri Neuendorf

Most people have probably never heard of Nukus in western Uzbekistan. Yet, tucked away in this corner of the world resides the world’s second largest collection of Russian avant-garde art, Al Jazeera reports.

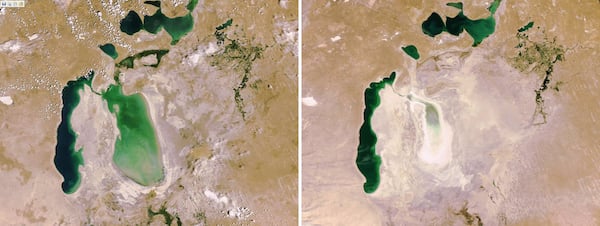

The area is perhaps best known for its environmental disasters, being a former nuclear test site and the site of the desiccation of the Aral Sea.

The Aral Sea desiccated after the Soviet Union redirected water to central Asia for cotton production.

Photo: HO/AFP/Getty Images via Al Jazeera

So how did this priceless collection end up there? It got there thanks to Russian artist Igor Savitsky, who came to the region in 1950 on an archaeological expedition from Moscow and decided to settle there.

An educated and cultured man, Savitsky became director of the Nukus Museum in 1966 and made it his mission to find forbidden Russian avant-garde works that have been lost.

It was a difficult task. Artists who did not conform to the communist-approved ideals of socialist realism were purged—facing imprisonment and even death. Many fled Russia and settled on the fringes of the Soviet Union.

Savitsky traveled to Uzbek and Russian cities where family members of banned artists kept paintings stashed away in basements and attics. Because the risk of being caught with forbidden art was so great, in some cases masterpieces were nearly discarded.

Savitsky saved works by Russian masters such as Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky, and Marc Chagall. Without his intervention, they would have almost certainly been lost, irreparably damaged, or even destroyed.

“He brought back full railroad wagons,” Valentina Sycheva, the museum’s chief curator, told Al Jazeera.

The museum’s storage facility is overflowing with first-class examples of Russian avant-garde art

Photo: Timur Karpov via Al Jazeera

At the time, most of the artists ranged from the obscure to the completely unknown. “These days, he is an authority figure, but at the time they saw him as a weirdo, an absolute nutcase,” museum director Marinika Babanazarova admitted.

Following Savitsky’s death in 1983, Babanazarova—a former English literature major—took charge of the museum. Although she admits she was terrified of “the feeling of responsibility that fell on me,” she resolved to preserve the collection and promote the museum internationally.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, one of the first foreign visitors in the 1990s was Al Gore, then a US senator, and a resulting New York Times article put the institution on the map.

Today, the museum is thriving, expanding into two new buildings and attracting visitors from around the world.