Art World

This Aerial Photographer Captured Images of the Mass Burials on Hart Island. Then, the New York Police Department Confiscated His Drone

The photographer says undercover cops were called to the scene after just 15 minutes.

The photographer says undercover cops were called to the scene after just 15 minutes.

Sarah Cascone

The New York Police Department detained photographer George Steinmetz last week and seized the $1,500 drone he had been using to document Hart Island, where the city has been burying unclaimed bodies of New Yorkers who died of COVID-19.

In New York City, it is illegal to launch or land aircraft, including drones, outside of designated airfields, but Steinmetz claims he took off from a sleepy parking lot on City Island in the Bronx and only flew half a mile over the water to Hart Island, avoiding LaGuardia’s airspace.

A representative of the NYPD told Artnet News that “drones are illegal to fly in New York City except for authorized areas. The areas approved for flying drones are very limited and set by the [Federal Aviation Authority].”

But Steinmetz believes the police’s concern “was not about public safety,” he told Artnet News. “It is clear to me that the the city was using this law as a pretext to stop people from photographing what was going on on Hart Island.”

Inmates from Rikers Island jail have been digging graves on Hart Island, the city’s potter’s field to bury the bodies of New Yorkers whose families could not be reached to claim them. As the death toll overwhelmed city morgues, many victims of the coronavirus have been sent to Hart Island for internment.

“It’s a mass grave,” said Steinmetz. “I think it’s very embarrassing for the De Blasio administration that they’re treating the city’s poor like toxic waste.”

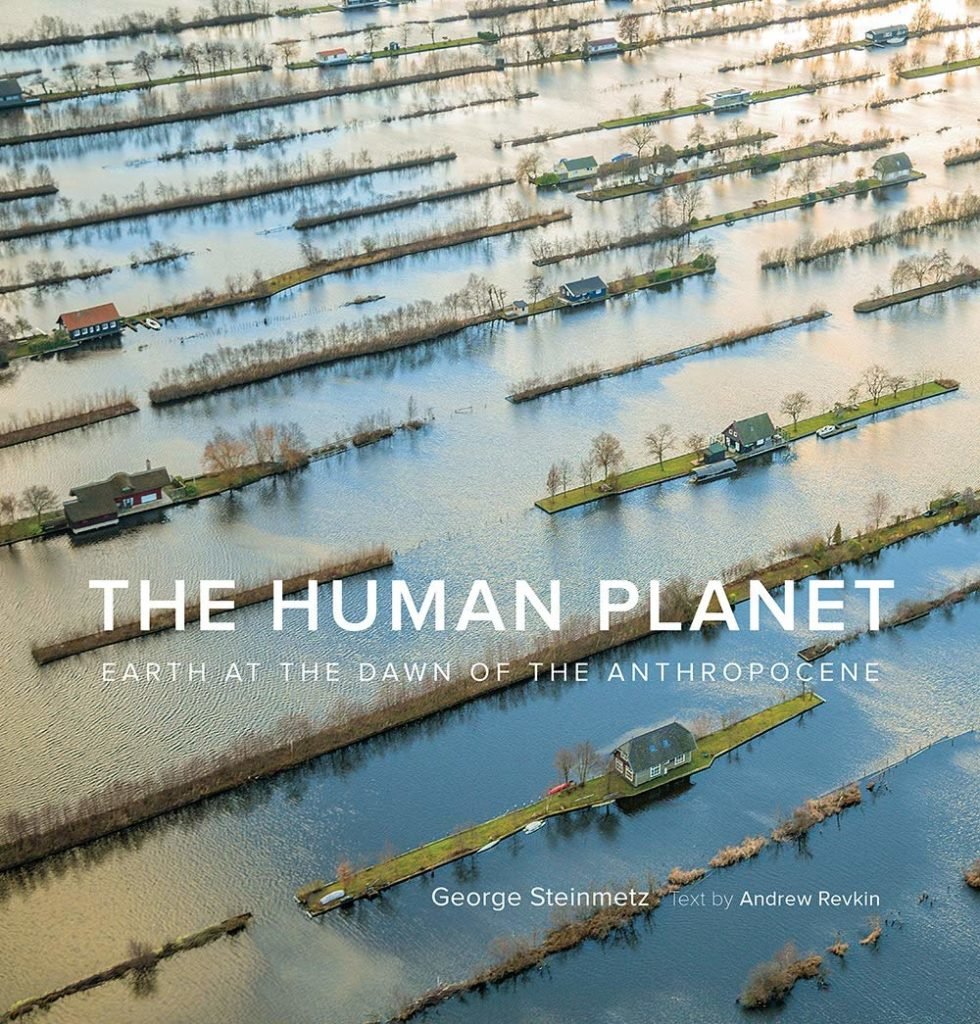

An accomplished aerial photographer whose work often appears in National Geographic, Steinmetz previously photographed New York City from helicopters and rooftops for his 2015 book New York Air: The View From Above. With the publication of his latest book, The Human Planet: Earth at the Dawn of the Anthropocene, which came out earlier this month, he was inspired to take to the skies once again with an eye toward documenting the streets of New York during the unprecedented shutdown triggered by the coronavirus pandemic.

The Human Planet: Earth at the Dawn of the Anthropocene by George Steinmetz. Published by Harry N. Abrams.

“I thought, wouldn’t it be interesting to look at the city in lock down, the city in paralysis from the air?” Steinmetz said. The results—slightly delayed because his regular helicopter pilot contracted coronavirus—offer a remarkable contrast to earlier photographs of bumper-to-bumper traffic and crowds in public spaces like Bryant Park.

“The avenues are empty, the bridges and tunnels are empty. It looks like a futuristic movie, like Planet of Apes or something,” said Steinmetz. “It’s like a dead city.”

Although he’s a licensed drone operator, Steinmetz had never used one in the city before—“Manhattan is not a good environment for a drone,” he said. But since his helicopter ride was in the afternoon, to show the great contrast with normal rush hour traffic, he reasoned that a quick drone outing at dawn, when internments take place on Hart Island, seemed harmless enough given that the island has more in common with a quiet New England fishing town than bustling Manhattan.

But about 15 minutes later, undercover police officers descended and confiscated his drone (though he removed the memory card first).

Later that afternoon, Steinmetz approached again via helicopter, but air traffic control refused to give permission to approach Hart Island below 1,000 feet—even though he says he had seen a channel 11 news chopper hovering at about 300 feet that morning prior to his drone flight. “It seemed like word was out they didn’t want press,” Steinmetz said. “It was very odd.”

Jason Kersten, a spokesperson for the Department of Correction, which oversees the Hart Island and its operations, cited “a longstanding policy of not permitting photography of an active burial site from Hart Island,” telling Gothamist “it is disrespectful.”

Steinmetz received a summons to appear in court in 90 days from the incident.