Art World

Oakland Developers Don’t Want to Pay for Public Art

They say they're being forced to convey "government messages."

They say they're being forced to convey "government messages."

Sarah Cascone

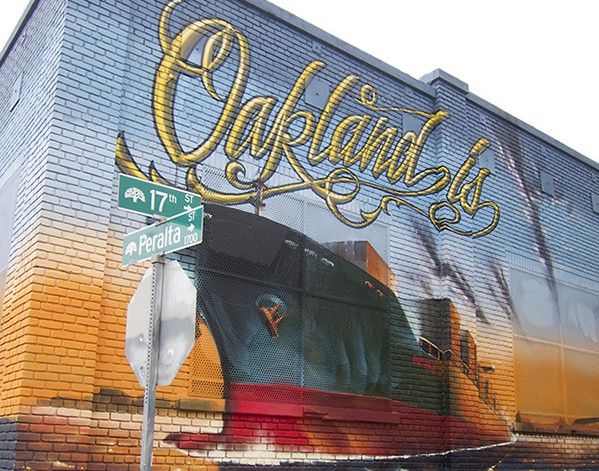

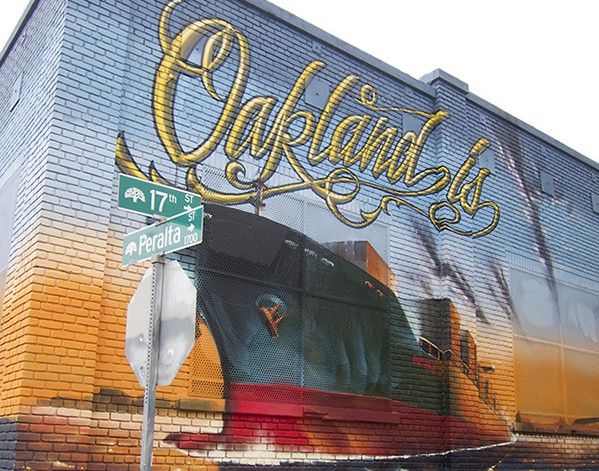

One of the “Oakland Is” murals created by graffiti artists Norman “Vogue” Chuck and Mike “Bam” Tyau.

Photo: Oaktown Art.

Bay Area developers are fighting a new law that requires one percent of the budget for non-residential construction projects and 0.5 percent for new residential buildings to be allotted for public art.

The Building Industry Association is suing the city of Oakland, claiming that the new municipal code constitutes an unconstitutional imposition of forced speech. Basically, they don’t want to have to shoulder the expense of the public art that they think should be paid for with taxpayer dollars.

Courthouse News reports that the complaint argues the ordinance “violates the association’s members’ right not to engage in speech.”

Developers do have the option of contributing to the city’s Public Art Project Account in lieu of commissioning a project of their own.

Oakland has had a similar stipulation on the books applying to city capital improvement projects since 1989, but the new law expands art requirements to private development as well. It is based on similar legislation from the neighboring city of Emeryville.

Mike Christian, The Bike Bridge (2012), created with the help of 12 girls from Oakland high schools for the city’s Uptown ArtPark.

Photo: Mike Christian.

Photo:

Other cities that have similar laws on the books include Los Angeles, where geographic restrictions on the placement of public artworks has led to millions of dollars in unused art funds. In New York, only city-funded construction has to put money toward public art, and local residents now have even more input into the art selection process.

The Oakland ordinance states that the new development regulations “will encourage and require works of art in new development in Oakland, which is important for the vitality of the artist community as well as the quality of life for all Oakland residents.”

The Building Industry Association doesn’t see it that way. “The First Amendment forbids the government from forcing property owners to fund and convey government messages, including through art, as a condition of granting a permit,” reads the complaint.

Protests over public art projects are nothing new, but they tend to spring up over other issues, like its ugliness and high cost (Long Island City’s Pepto-Bismol pink “Gumby” Sculpture) or the fact that an out-of-state artist was being commissioned (Sacramento commissioned New York-based Jeff Koons to create his abstract sculpture Coloring Book for its new Sacramento Kings’ arena).

A controversial obelisk by local artist Ellen Kim erected by the Temescal Business Improvement District in Oakland for $10,000–20,000.

Photo: Karen Hester.

Reportedly, Oakland developers’ real problem is the increase in development costs that the new law would bring with it. While a similar law is tolerated in San Francisco, where building costs are about the same, real estate development is allegedly far less lucrative in the East Bay.

“Commissioning more public art might be a laudable goal, but the responsibility to fund it should rest with city government and taxpayers as a whole, not with builders and the home buyers and renters who will have to pay more,” Tony Francois, an attorney at the Pacific Legal Foundation, which is representing the Building Industry Association, told California Real Estate Rama.

“Already, there are thousands of homebuilding projects that have been approved in Oakland, but not acted upon, because high construction costs make them unaffordable,” he added.

In Oakland, Greg McConnell, president of the local Jobs and Housing Coalition, told the Contra Costa Times, “the revenue isn’t sufficient” to justify the same art spending as across the Bay. (Presumably, it isn’t worth fighting such laws in tiny Emeryville, which has only 1.2 square miles of land compared to Oakland’s 55.8).

The city council passed the law on December 9 of this past year, and the legislation took effect on February 8. It affects residential buildings with more than 20 units and commercial projects costing more than $300,000.

“These developers are acting like this is highway robbery,” Eric Arnold, a spokesman for the Community Rejuvenation Project, told the Times. “It’s not asking too much of those who are building in Oakland . . . to support art that will keep Oakland cool.”

“Public art is how cities become art cities. You don’t become a world-class city without world-class art,” he added.