Art & Exhibitions

What Is the Role of a Museum in One of Polarized America’s Most Purple States? Oklahoma Contemporary Offers a Case Study

The opening may be delayed, but Oklahoma Contemporary reflects big changes and ambitions in the Oklahoma City.

The opening may be delayed, but Oklahoma Contemporary reflects big changes and ambitions in the Oklahoma City.

Menachem Wecker

Clad in a turtleneck and chic blazer, architect Rand Elliott—a dead ringer for the magician Penn Jillette, at least from certain angles—leaned back onto a couple of the 16,800 aluminum “fins” that comprise Oklahoma Contemporary’s facade. It was a gloomy day, but he explained that his design of the new museum reflects the city’s rapidly changing light. At different times, the sky’s color can turn the building’s “skin” pink, navy blue, or yellow.

“We planned that, hoped that would happen, and chose the proper finish to do this,” he said.

Elliott avoided mirrored surfaces on the building because they would diffuse light and sparkle. But metaphorically, the art center is poised to offer the city a self-portrait. The most important color the building reflects may be purple—not of a stunning Oklahoma sunset, but the city’s stereotype-eschewing nature in this election year.

Architect Rand Elliott at Oklahoma Contemporary. Photo: Menachem Wecker.

“The city is politically very purple,” said Oklahoma City Mayor David Holt. “People around the country seem to have accepted that Texas can be red, Austin can be very blue, and that those two things can happen simultaneously. I guess maybe they haven’t quite wrapped their mind around the idea that Oklahoma City could be very purple.”

Outsiders may be aware that every Oklahoma district went for Donald Trump in 2016, and the last time a Democrat carried the state in a presidential election was 1964, when President Lyndon B. Johnson was elected. Yet the city’s winds blew in a different direction two years ago when Democrats flipped Oklahoma’s 5th congressional district, and fifth-generation Oklahoman Kendra Horn became its first elected Democrat in 44 years.

As museums work to appeal to constituents, regardless of political affiliation, in an increasingly polarized political moment, the Oklahoma Contemporary offers a case study in retaining institutional convictions while remaining welcoming and approachable.

Oklahoma City hasn’t registered on many people’s radars the way Holt—the Republican mayor and former board president of Oklahoma Shakespeare in the Park—would like. The city that birthed the Flaming Lips used to be the blue-collar step-sibling to more sophisticated Tulsa, but has since outpaced its northern neighbor’s arts offerings.

“Our first challenge is that they don’t think of us at all, and then if you force them to think of us, they may have silly images of the Wild West, the musical, college football, or something,” Holt said.

That’s why the stakes are high for Oklahoma Contemporary, a 53,916-square-foot, custom-built space that sits on 4.5 acres and includes a dance studio, classrooms, studios for ceramic and fiber artists, and 8,000 square feet of gallery space. Its construction was one of the aims of a $30 million capital campaign, with Oklahoma City native Ed Ruscha as honorary chair, which has brought in $26 million to date from more than 200 donors. Among the largest donors are the Chickasaw Nation, museum founder and president Christian Keesee, and bank owner George Records and his wife Nancy.

Rendering of Oklahoma Contemporary Facade. Courtesy of Oklahoma Contemporary.

Keesee founded the museum in 1989 as the City Arts Center in State Fair Park, a comparatively isolated location without much foot traffic, while the new downtown location has a dedicated stop on the new city streetcar. As before, the museum will operate without a collection, but it expects its increased programming, classes, exhibitions, and performances in its much larger space to draw 100,000 visitors per year.

In an unfortunate turn of events, however, the museum was forced to delay its grand opening festivities last weekend after a visiting Utah Jazz player, in town to play the Oklahoma City basketball team the Thunder, tested positive for coronavirus.

Before the museum closed its doors, Artnet News had a chance to visit. Oklahoma Contemporary, whose facade echoes Reykjavík’s iconic Hallgrímskirkja, is the city’s biggest financial commitment to its cultural character to date. “This is really a statement of where we are—that we feel as a community that we could sustain a contemporary art center featuring exhibits that are not literal Western paintings,” Holt said.

Camille Utterback, Entangled (2015). Photo by JKA Photography.

The inaugural exhibition, “Bright Golden Haze” (whose opening is now delayed), immediately reveals a different kind of work than the Frederic Remington sculptures or William R. Leigh paintings that one might associated with the Wild West. The show, whose title derives from the opening words of the musical Oklahoma, explores the way artists use light—from Olafur Eliasson’s Black Glass Eclipse, a rotating disc that bathes the room in yellow-orange, to work by Light and Space pioneers Robert Irwin and James Turrell.

Meanwhile, Tavares Strachan’s neon, which spells out the phrase “I Belong Here,” gestures toward a kind of hospitality that may surprise those who expect Oklahoma to conform to a monolithic conservative flavor. And it’s not the only such symbol. A large sign in the lobby reads: “We honor the Indigenous people who inhabited these lands before the United States was established,” adding that 39 distinct tribal nations reside in Oklahoma. Another large text, this one in a “learning gallery,” states that “this is an inclusive space, open to people of every background, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation gender/gender expression, language, immigration status, ability, age, and faith/worldview … You are welcome here.”

Teresita Fernández, Golden (Odyssey) (2014). Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul.

According to Oklahoma Contemporary’s artistic director Jeremiah Matthew Davis, the museum tries to get ahead of potential controversies by contacting local communities ahead of potentially sensitive exhibitions. (For example, curators spoke with city police and the local chamber of commerce before a graffiti show, which they knew some might see as vandalism.)

“We’ll see once we have this brighter spotlight on us, there may be some various perspectives on any number of things that we’re doing,” he said, noting that a current photography show, “Shadow on the Glare,” provides labels in Spanish and Vietnamese, the city’s two most-spoken languages other than English.

In the Oklahoma office of his family foundations and his banking, oil, and gas businesses, museum founder Christian Keesee agrees with the mayor about out-of-towners’ assumptions. As someone who divides his time between Oklahoma, Colorado, and New York, where he sits on the Frick Collection’s board and is a trustee emeritus at the American Ballet Theatre, Keesee is aware of how his native city strikes different people.

“Our only political agenda is art for everyone. Period,” said Keesee, a member of the Kirkpatrick family (on his mother’s side), which played a central role in the city’s development and growth, and whose philanthropic efforts span the arts, education, the environment, and humane treatment of animals. “I hope that people would feel comfortable coming to Oklahoma for any reason, just as I hope Oklahomans would feel comfortable going to California or New York,” he said. “I know they do.”

Part of that mission will be carried out by the museum’s new leadership. Sitting in his office at Oklahoma Contemporary, with a clear view of the state capitol and a deep-blue balance ball chair in front of his computer, Eddie Walker, the museum’s executive director, talked about the his decision to join the museum last April after 30 years at the Oklahoma City Philharmonic Orchestra, where he had been executive director since 1999.

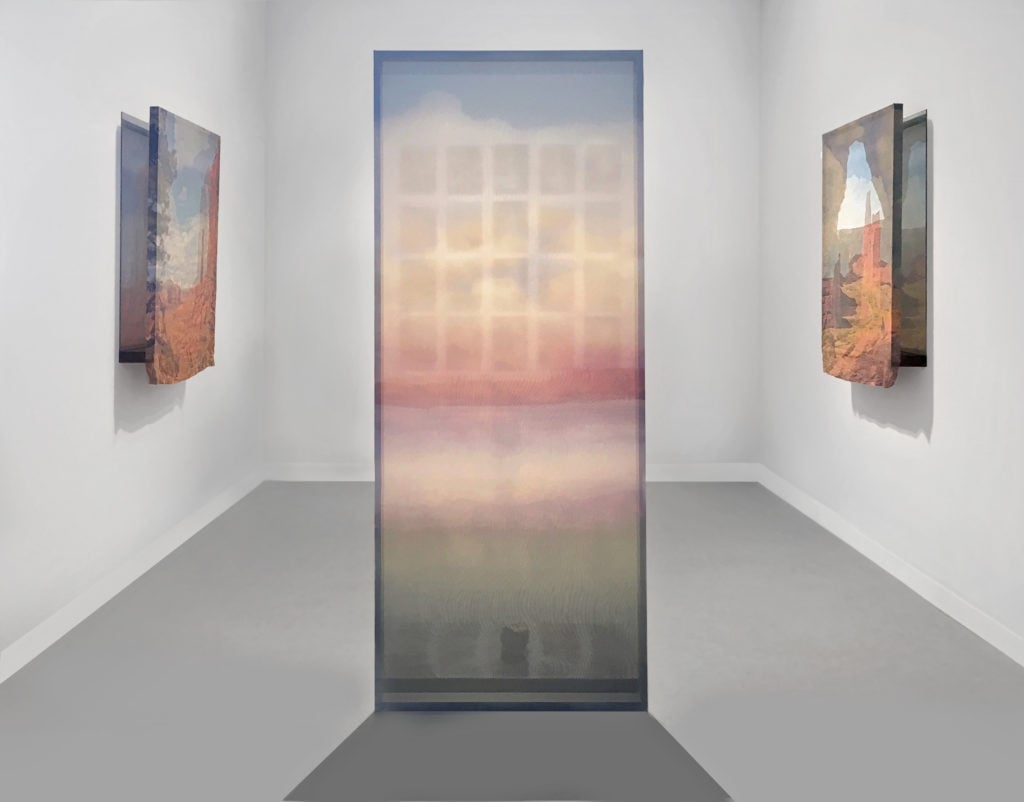

Installation view of Doty Glasco’s work in “Bright Golden Haze.” Courtesy JR Doty.

When Walker saw the building renderings two years ago, he thought it was going to be a fun job for somebody to run the institution. “Who knew Chris Keesee was going to call me and talk about the position?” he said. “I was sweating. I said, ‘Well, I’d be lying if I wasn’t interested.’”

“I don’t think we even understand what we will or can become,” he said. “I really believe that as we figure out what the building can do—because it’s so flexible—I think we’re going to have two or three years of just fun exploration, dreaming, and visioning. We’ve already had patrons and visitors make suggestions, and some of them are darn good.”

The museum—whose new location is north of the city’s Automobile Alley and the memorial commemorating the victims of the 1995 bombing—sees its mission as twofold. In addition to offering itself up as a welcoming place in a divided city, it is also working to boost arts education in a region where it has been decimated. “Arts education within public and private and in homeschooling has been basically eliminated over the last 15 or 20 years,” Walker said. “We know that we’re going to have busloads of kids coming from Tulsa and from the outside of Oklahoma City to see what we’re doing and to take part.”

Oklahoma Contemporary’s shows will have regional appeal, he thinks. “My hope is that what we do, and the currency we print in the form of arts exhibitions, are going to be appealing to people in Dallas, Tulsa, Kansas City, and Little Rock and that they’re going to come in the same way that Oklahomans will go to those places to see exhibitions that are of interest to them.”

A decade from now, Keesee will evaluate Oklahoma Contemporary’s effectiveness by the people who have participated in its programs. “Hopefully the little pebble that goes into the water will create ripple effects that educate and enlighten people,” he said. “If we can just give a lot of people a little bit of exposure, that’s going to have a terrific impact on our community and our state and hopefully the region.”

Rendering of Oklahoma Contemporary Facade. Courtesy of Oklahoma Contemporary.

Museum visitors will find a few surprises in the building itself if they keep their eyes peeled. For one thing, they will notice three diagonal beams holding up a corner of the overhang, while a fourth doesn’t touch the roof—a gap in reaching appendages reminiscent of the space between Michelangelo’s Adamic and divine fingers. “This is my tall grass coming out to support the canopy, that there just happens to be one that decides, ‘I don’t want to play with anybody else,’” said Elliott, the architect. “I’ve had people come back and go, ‘Dude, you missed it.’”

In the lobby, Elliott points out a rectangular panel surrounding a digital screen behind the admissions desk. “It represents the classic, most beautiful proportion there is, created by Vitruvius in 45 BC,” he said. “This is the proportion of 1:1,618, which is the golden section or the golden ratio. We felt like it is really important to take technology, which is 21st century, to something that is ancient that is germane today.”

It’s hard to imagine a better metaphor of reaching to the ancient past to frame the contemporary to explain a museum that may well be Oklahoma City’s most effective ambassador to the country, and indeed to the world. Put differently, the museum may well be singing to itself in coming years, “I’ve got a wonderful feeling,/Everything’s going my way.”