Around 2:30 a.m. this past Saturday, a makeshift jazz quartet was just getting going on the shallow stage at the Mutual Musicians Foundation’s squat, two-story building on Highland Avenue in Kansas City, Missouri. The building itself isn’t much to look at: a concrete patio outside and a faint mustiness radiating from the aged wood paneling inside. Upstairs is a single room, lined with curling pictures of jazz legends and filled with mismatched tables and folding chairs.

It’s likely the only national historical landmark that has a liquor license good until 7 a.m., and it’s where, behind the saxophonist bleating out a Wayne Shorter riff, another saxophone, dripping in gold netting and cast in resin so it gives off a nacre glint, is suspended from the ceiling. The sax is half of Claim, artist Nari Ward’s effigial installation referencing Charlie Parker, Kansas City’s native son and jazz’s patron saint, who played in this same space and whose childhood home around the corner has been razed. All that officially ties the greatest innovator of bebop to the city now is the house’s lot registration number in tax records, which Ward has rendered on a lightbox and affixed to the fence outside the club.

Nari Ward’s Claim (2018) at Open Spaces Kansas City, 2018. Courtesy of Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York.

Claim, which concerns memory and its absence, is part of Open Spaces, Kansas City’s first crack at a contemporary art biennial. It is also a good example of the exhibition’s guiding principle, which is less concerned with the contemporary art world having overlooked Kansas City as a cultural capital and more concerned with its own potential to become one.

Origins of a Biennial

The germ of Open Spaces sprouted a few years ago as several disconnected ideas. The local philanthropists Scott Francis and Susan Gordon, wanting to bring the scale and prestige of the German public sculpture show Skulptur Projekte Munster to the Midwest, approached the curator Dan Cameron. The founder of Prospect New Orleans and former curator of biennials in Taipei, Istanbul, and Ecuador is something of a pied piper for the international art world, practiced at focusing its attention on places it had previously not given much thought. Meanwhile, around the same time the couple began talking to Cameron, Kansas City mayor Sly James contacted him about bringing fresh cultural programming to the city.

The resulting compromise between these two ambitions, which began this past weekend and runs for the next two months, is Open Spaces. The show splits the difference between a straight-ahead visual art biennial and a performing arts festival. (Imagine the German quinquennial documenta crossed with a landlocked Governors Ball, but with better barbecue.) This bifurcated personality means that stadium-size music acts like the Kansas City-born Janelle Monáe, who will perform in October, share the bill with internationally recognized artists like Nick Cave.

Of the 46 artists who contributed work around town, 10 are Kansas City residents. Another 10 hail from other parts of Missouri and Kansas. How these artists’ work, which is often invested in the cultural and political landscape of the region, brush up against those from the coasts or cities as far away as São Paulo and Berlin, is a compelling question that arises in any biennial. The results here feel especially keyed to a level of engagement that often tips into urgency.

Where the Local Meets International

An affecting video by artist Brian Hawkins, who is from Lawrence, Kansas, and Tonya Hartman, a local transplant originally from New York City, concerns the daily minutiae of a group of teenagers whose families have immigrated from places like Guatemala, Rwanda, and Mexico and are enrolled in an English-language class at Wichita East High School. Any expectation of political heavy-handedness or didacticism (it screens at the Jewish Vocational Services Center, which provides immigration and refugee services) never materializes. Instead, it casts a gentle focus on the students’ unique personalities and their individual responses—cautious, reticent, enthralled—as they make sense of their new Midwest environs.

Anila Quayyum Agha’s This is NOT a Refuge (2017-18). Photo by Steve Prachyl.

A mile away at the Kansas City Art Institute, Anila Quayyum Agha’s This is Not a Refuge strikes a similar chord. A stout shed made of perforated metal, it’s a beautiful structure that makes for a lousy shelter. Agha, who is based in Indianapolis and won both the public and jury votes at Michigan art competition ArtPrize in 2014, is adept at subtle confluences like these. Refuge, which assumes a distinctly, almost satirically American architectural vernacular but is spliced with Islamic inflected filigree, was fabricated in Kansas City in conjunction with the manufacturer Zahner, who has produced the metal cladding for every Frank Gehry building to date.

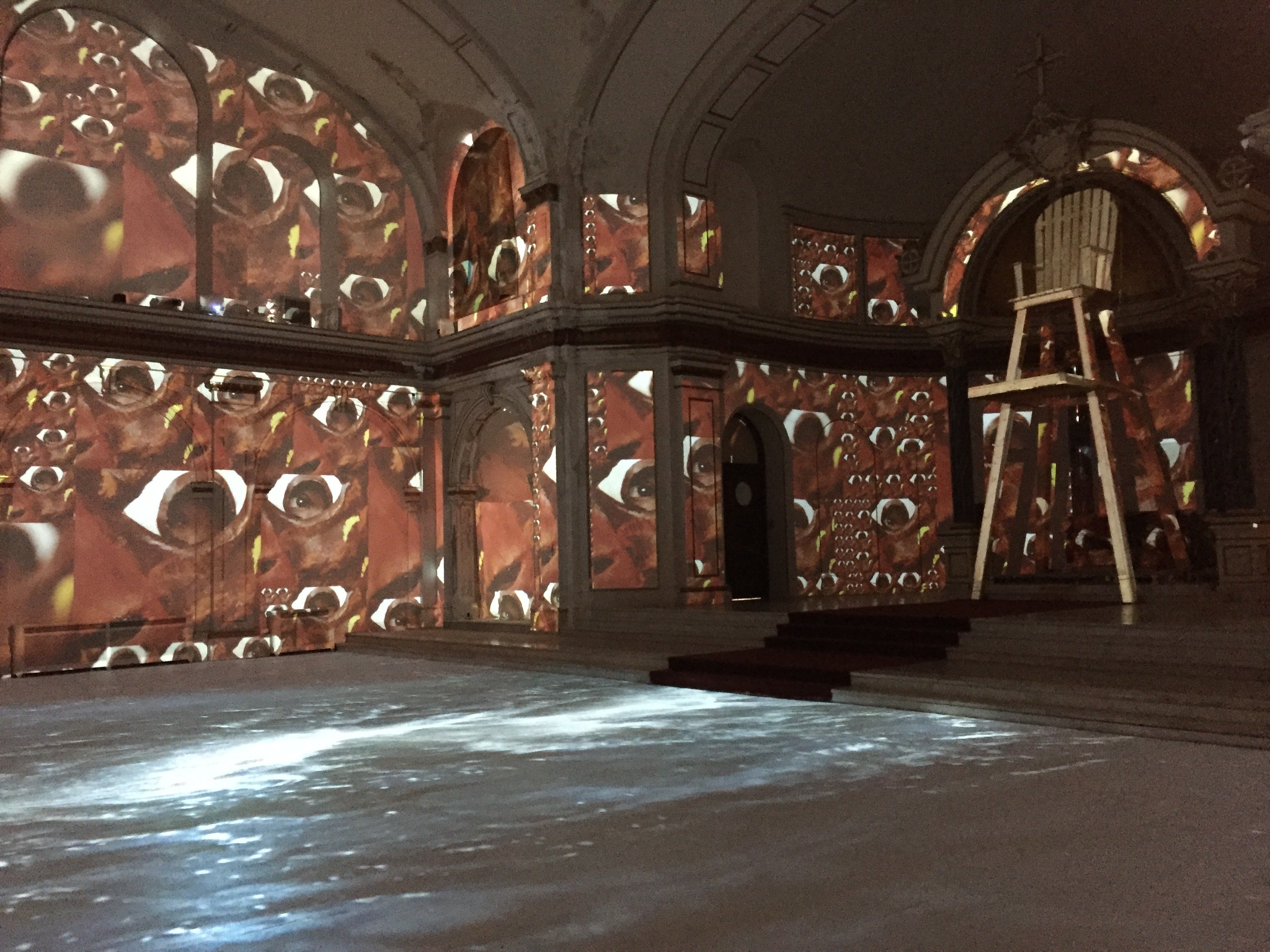

Nick Cave is most associated with Chicago, but was raised locally and studied at the Kansas City Art Institute. Hye Dyve, his contribution to Open Spaces, occupies a deconsecreated church in the Oak Park neighborhood, which he’s filled with a disturbing 14-channel video installation. A projection of dark, rushing water onto the floor threatens to wipe your feet out from under you as hundreds of menacing cartoon birds plop down from the rafters onto the walls before giving way to Cave’s eye peering out from one of his signature soundsuits. The space, devoid of pews, suggests an after-the-flood moment, civilization returned to nature. But the mood is claustrophobic rather than purifying, like being in the belly of a ship, possibly bound from Africa, possibly transporting hundreds of people condemned to slave labor.

Cave’s piece alludes to Kansas City’s long history of racial strife, one of the country’s most acute. The city’s schools weren’t integrated until 1973 and decades of redlining and blockbusting means its reverberations persist. Today, it’s one of the five most economically segregated cities in the country. Kansas City’s population of just under half a million spreads out across 319 square miles, which translates into, yes, a lot of open space. (The biennial’s name comes from British sculptor Antony Gormley, of all people, who, when asked his impressions of Kansas City while in town a few years back. was reportedly struck by “all this green, all these hills, all these trees.”)

Swope Park in Kansas City. Photo courtesy of Open Spaces Kansas City.

All that space means you don’t see very many people in any one place, least of all in Swope Park, which is more than twice the size of Central Park. So it’s not an accident that Swope Park, east of the historic racial dividing line of Troost Avenue, is Open Spaces’ fulcrum. The goal, hinted at in hushed tones over the course of a few pre-opening cocktail receptions, is to get people—namely, white people—to visit a side of town they ordinarily wouldn’t.

On the Art Hunt

Like other biennials of its size, Open Spaces’ diffuse approach makes it feel a bit like a scavenger hunt. Joyce J. Scott’s evocative sculpture of Harriet Tubman, placed in a corner of Union Station, is a coy nod to the comings and goings of overground travelers. It is about an hour’s bus ride to Alexandre Arrechea’s contribution to the show in Swope Park. Arrechea, a member of the ’90s Cuban art collective Los Carpinteros, has erected a surrealist monument to civic pride—a giant meat thermometer with piano keys replacing the temperature dial.

Nearby, Lee Quiñones, the New York-based progenitor of street art, worked in concert with the Kansas City graffiti community (yes, there is one) to produce Skin Deep, a public mural at the Kansas City Zoo. Abstract panels of cheetah coats and zebra stripes ring the exterior of the Zoo’s IMAX theater like a frieze, and are bookended by panels of black and white, a subliminal investigation into learned behavior and abstract racial constructs.

Alexandre Arrechea’s Meat and Music (2018) at Open Spaces. Photo: Kevin Moravec, courtesy of the artist.

Open Spaces’ multivalent civic-mindedness has a forebear (by a few weeks) in Front International, the first triennial in Cleveland, which debuted earlier this summer. In terms of an organized municipal effort to will itself into the cultural conversation, it also has more than a bit in common with what’s going in Dallas now, another city where the hearts and pockets of the city’s collectors, cultural institutions, and local leaders have aligned in a bid for a place on the national stage. But where Open Spaces diverges is in its gestalt effect; the work in Kansas City is less bothered by the flitting diversions of the market, and more occupied with what’s going on at home.

For someone not from Kansas City, Cameron makes a convincing booster. “We don’t want our young and ambitious artists to think they can only go to a city of three million or more,” he said. “When Jackson Pollock came to Kansas City to study painting with Thomas Hart Benton, there was a reason. Kansas City meant you would get a grounding in a very particular body of knowledge and tradition. And we know what Pollock went off to do, but he went off to do it. We wanted to make it possible for Kansas City artists to have access to the world, and for the world to have access to the best of Kansas City, and for it to be a natural symbiosis. For it to really just flow.”