Art & Exhibitions

Can the FRONT Triennial Redefine the Meaning of Cleveland? Yes, But Not in the Way You Think

Tim Schneider

At the opening press conference for Cleveland’s inaugural FRONT International triennial, Michelle Grabner, the renowned artist and curator who spent much of the past two years shaping the new event, sounded a note of caution: “If you haven’t seen the entire exhibition, you haven’t seen the exhibition.” Even falling short of that challenge, though, any honest attempt will do more than just introduce viewers to an array of present-conscious and forward-looking artworks. It will also expose myriad nuances of a city and a region too long misunderstood.

Seeing the entire exhibition is no mean feat. Officially titled the FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art, the show presents 111 artists across 26 different sites, including about a dozen cultural institutions and galleries, two historic churches, one Frank Lloyd Wright house, and even a decommissioned steamship. (Some of the locations and artists are owed to Grabner’s former co-curator Jens Hoffman, who departed FRONT in November 2017 in advance of separate sexual harassment allegations.)

Within Cleveland proper, FRONT-activated sites stretch from Hingetown on the West Side to Glenville in East Cleveland. And despite the exhibition’s titular focus on Cleveland, various artist projects are also hosted in Akron (about 40 miles south) and Oberlin (about 35 miles southwest). That means you’ll need a car to experience everything, but, if it’s any consolation, it’s still vastly more convenient than the extra international flight that was required to take in all of documenta 14.

Besides, the drive time will give you a much-needed opportunity for some heavy thinking.

Ironically, one of the last works I saw on a whirlwind two-day press tour of the exhibition provides the best entry point for my thoughts on FRONT. Commissioned by the triennial for the Ellen Johnson Gallery of Oberlin’s Allen Memorial Art Museum, Barbara Bloom’s The Rendering (H x W x D =) encapsulates both the predicament long faced by FRONT’s home city and the way the ambitious, multi-venue exhibition hopes to help solve it.

The Rendering comprises two main elements. The first is a salon-style hanging of 20 works Bloom selected from the Allen’s collection. The catch is that she outfits each individual piece with a custom box hiding everything except its images of architecture. These are revealed only by precisely cut rectilinear openings. According to Allen curator Andrea Gyorody, it is Bloom’s way of “narrowing in on the details that she wants you to pay attention to, and effacing everything else”—a technique she has used before, as well as a direct comment on the architect Robert Venturi, whose aggressive design for the Johnson gallery has effectively man-spread itself onto every artwork installed there since 1970.

Occupying the gallery’s floor are a number of sculptures by Bloom that “reverse-render” in three dimensions various two-dimensional structures depicted in a handful of prints and drawings also culled from the museum’s holdings. Expanded into our physical space, they reveal qualities we might not have noticed if we’d simply glanced at the page we were given. In this way, Bloom counterbalances her “framing wall” by mining her subjects’ unnoticed virtues and complications, then re-presenting them to us in fuller form than ever.

Barbara Bloom, The Rendering (H x W x D =), 2018. Installation view at the Allen Memorial Art Museum. Commissioned by FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art. Photography © Field Studio.

A similar push-pull dynamic animates FRONT and the region that birthed it—at least for someone like me who grew up in Northeast Ohio, or someone like FRONT Executive Director Fred Bidwell, who initiated the triennial in the city he adopted years ago.

“To just categorize Cleveland as ‘Rust Belt’ or ‘reviving Rust Belt’—those are simplistic stories that are really so incomplete and so stereotypical,” Bidwell said. “It really doesn’t represent the town.”

For a taste of what Bidwell means, consider this: The largest employer in Northeast Ohio has for years been the Cleveland Clinic, one of the most respected medical centers in the world. A June 2018 report by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics identified education and health services as Cleveland’s largest industry. Manufacturing ranked fifth by workforce size, with less than half as many jobs. Clevelanders today are much more likely to work in a hospital, school, or research facility than on an assembly line.

Marlon de Azambuja, Brutalismo-Cleveland, 2018. Installation view at the Cleveland Museum of Art. June 3, 2018–December 30, 2018. Commissioned by FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art. Photo © The Cleveland Museum of Art.

Yet for people who call the Cleveland area home, simplistic stories have defined the way the rest of the world looks at us for decades. Despite the presence of a world-renowned encyclopedic museum, one of the best orchestras on the planet, a top-flight medical establishment, and multiple universities, almost every time that I’ve told non-art people where I’m from since leaving the region in 2001, the best outcome has been that they reference either LeBron James or the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

More likely, however, people who hear the word “Cleveland” tend to associate it with a wilted bouquet of outdated misfortunes, ranging from gut-wrenching professional-sports blunders to various civic embarrassments that I won’t further shame the city by resurrecting here. (And since LeBron just left Cleveland again, this time to play in Los Angeles, snide outsiders have regained another tired plan of attack.)

This is why those of us with roots in the region tend to share an underdog pride. Fittingly, when I saw the first showing of LA Heavy, the artist Casey Jane Ellison’s FRONT-commissioned stand-up performance, the emcee who introduced her was wearing a local classic: a t-shirt reading, “Cleveland Against the World.” (If you live in Cleveland, you know that it has a t-shirt for everything, particularly its battle cries.)

Casey Jane Ellison, Untitled, 2018. Poster for LA Heavy. Commissioned by FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art. Image courtesy of FRONT.

This is what FRONT has to contend with. “There’s certainly a more positive story out there about Cleveland that I think people understand,” says Bidwell. “But currently it’s a bit too focused on rock and roll, sports, the food scene. FRONT is really here to polish that image, to include this narrative that Cleveland is a cultural and intellectual hub, as well. I think we really need that reputation in order to be a world-class city.”

As Bidwell’s comments imply, Cleveland has always been vastly more complicated than the straightforward narratives used to define it in the greater public imagination, even politically. Although Ohio played a key role in flipping the two most contentious national elections of my lifetime to Republican candidates with kindergarten-level attention spans, neither Cuyahoga County, which Cleveland anchors, nor Summit County, which Akron anchors, has gone red in more than two presidential races since 1960. (Hillary Clinton received 66 percent and 52 percent of the vote, respectively, in the two counties in 2016.) Completing the FRONT troika, Oberlin is so woke that it’s practically sci-fi.

And the triennial shows that the city and region have played more admirable political roles going much further back into history, too.

For Night Coming Tenderly, Black (2017), a site-specific installation at St. John’s Episcopal Church, the acclaimed photo-based artist Dawoud Bey decided to engage Cleveland’s significance in the Underground Railroad.

Code named “Station Hope” at the time, the church functioned as the last stop on the line before many fugitive slaves’ journeyed across Lake Erie to Canada and freedom. It is also one of the last stations still standing today. The photos Bey made and installed there primarily depict the landscape between Hudson, Ohio, and Cleveland. They are shot from the imagined perspective of escaped slaves traveling that high-stakes path—which, by necessity, was never precisely known—and printed in deep, velvety blacks.

Bey says this choice was influenced partly by Langston Hughes’s “Dream Variations,” a poem that reminded him that “the blackness of night can be… a tender space, which led me to think about the tender embrace of night that these fugitive black bodies were moving through.” Nighttime as a shield and protector, not a menace, shepherding brave souls through Northeast Ohio to liberation: it is powerful poetry.

But there’s also a far less flattering side to the city’s history of race relations. It took until 1976 for a judge to order Cleveland’s public school system to end the de facto segregation it had been quietly practicing for decades (and, specifically, for more than 20 years after the Supreme Court struck down school segregation in its transformative Brown V. Board of Education decision). More recently, much of the city’s national news presence owed to the slaying of unarmed African American 12-year-old Tamir Rice, who was shot by a (white) policeman while playing with a toy gun in a park on Cleveland’s West Side in 2014.

Installation view of Cyprien Gaillard, Night Life, 2015. Photography by Tim Schneider.

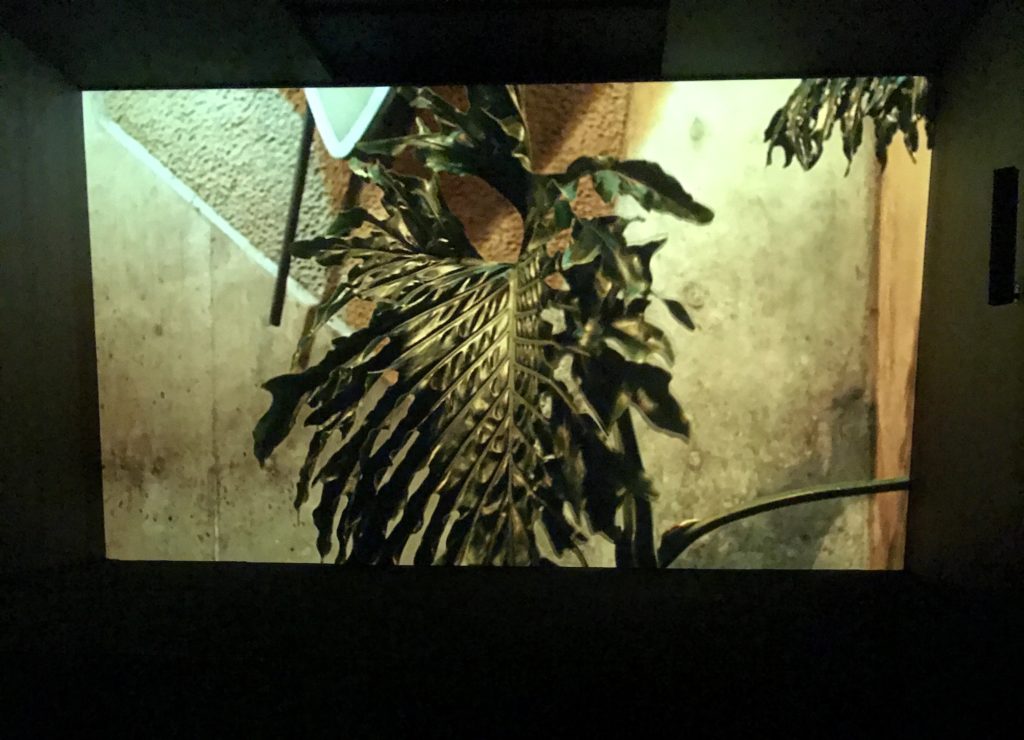

Cleveland’s racial struggles find resonant outlets at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and SPACES Gallery. In the museum’s top floor, Cyprien Gaillard’s mesmerizing 3D video Night Life (2015) connects Cleveland, Los Angeles, and Berlin through various overlooked yet loosely connecting historical threads. The piece begins with a slowly revolving view of the Cleveland Museum of Art’s edition of The Thinker, partially mangled by a 1970 bomb from the Weather Underground, the rogue network notorious for trying to use explosives to pressure American society into hastening racial equality. Night Life then transitions through swaying vegetation in Los Angeles to the two-day Pyronale fireworks extravaganza at Berlin’s Olympiastadion—the arena where Cleveland-raised Jesse Owens blew up Hitler’s “master race” pipe dream by winning four gold medals in the 1936 Olympics.

MOCA’s second floor features An Evening With Queen White (2017), a mixed-media installation by Martine Syms that interrogates the construction of black identity in the US. The two main walls in the museum’s Lewis Gallery primarily display what read as unaffected snapshots of African American men, women, and children living their everyday lives, interspersed with decorum instructions in white block text, such as “Say ‘Los Angeles,’ not ‘LA’” and “Avoid metaphor and analogy. Be clear.” A four-channel video piece captures actor Fay Victor portraying a character inspired by various matriarchal figures in Syms’s family and the Motown Records etiquette coach Maxine Powell, doling out pointed guidance on expected behavior in white spaces.

Martine Syms, installation view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art. July 14-September 30, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist and Bridget Donahue, New York. Photography by Field Studio.

A few miles away from MOCA, SPACES Gallery hosts Michael Rakowitz’s collaborative project A Color Removed, which invites Cleveland residents to help the artist take on the impossible task of collecting every orange object in the city. The project’s genesis is the orange “safety” tip missing from Tamir Rice’s toy gun—an absence that, according to police reports, spurred the offending officer to open fire on the pre-teen seconds after arriving on the scene.

Michael Rakowitz, A Color Removed, 2018. Photo by Tim Schneider.

With help from FRONT and the city, Rakowitz scattered dozens of collection bins across the city this spring, and SPACES now contains a room-wide assemblage of orange items culled from those containers. During an impromptu press preview, the artist said that he “wanted the installation to look like it wasn’t finished, because it never will be.” However, it does include an artwork by Tamir’s mother, Samaria, with whom Rakowitz worked closely throughout the project, and with whom he will hold a series of dinners at SPACES during FRONT’s run—each based on Tamir’s favorite foods and held at a date-shaped table that the artist will donate to the Tamir Rice Foundation after the triennial closes. (Rakowitz discovered during his research that “Tamir” means “date” in Arabic.)

Nor was Samaria Rice’s the only significant local contribution at SPACES. Leading to Rakowitz’s installation is a visceral group exhibition by Cleveland-based artists Amber Ford, Amanda King (in collaboration with youth photography group Shooting Without Bullets), M. Carmen Lane, and R.A. Washington. Their works all invoke various aspects of structural discrimination and its antidote in community action.

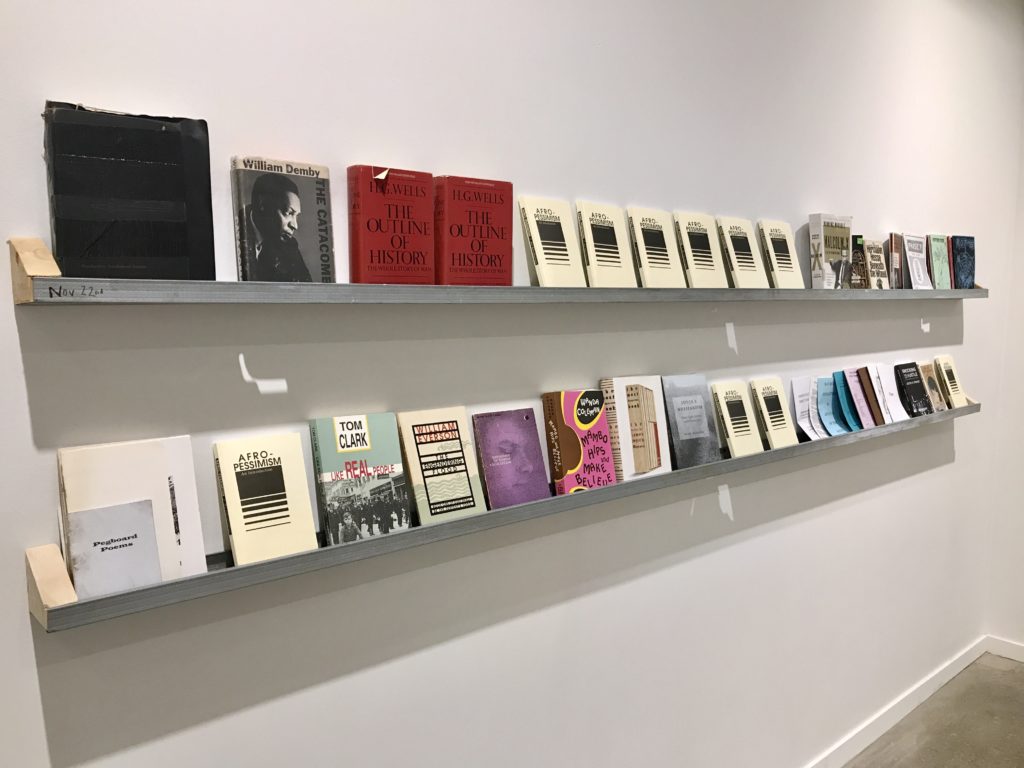

R.A. Washington, Grief Reads (detail), 2018, showing what the artist read between the night of Tamir Rice’s murder and the day of the responsible officer’s verdict. Photography by Tim Schneider.

After experiencing them in the context of FRONT, the themes surfaced by these works at MOCA and SPACES translate as both intimately connected to Cleveland and applicable to much of the US. Andria Hickey, senior curator at MOCA (and now soon to be senior director and curator at Pace Gallery), acknowledged at the museum’s preview event that “anytime you do a site-specific work, it reveals things about a place.” Yet these revelations have helped her understand Cleveland as “a microcosm of the whole country”—a portrayal that speaks to the double meaning of FRONT’s subtitle, “An American City.”

This duality is appropriate. As a landmark city in a state whose motto is “The Heart of It All,” Cleveland is both singular and universal. It offers enough resources, opportunities, and contradictions to tell almost any story—about economics, politics, race, culture, or anything else you’d like. And in the 21st century media environment, weaving a complex tale of any kind, about any place or any thing, feels at once increasingly daunting and increasingly necessary.

“I’m not naïve enough to think that an art exhibition is going to completely change the brand of Cleveland,” says Bidwell. But he does hope that FRONT establishes “a different story about the revitalization of Cleveland”—one that teases out its intricacies and pluralities. One that, in some sense, follows Barbara Bloom’s lead by reverse-rendering a flat image of the city into a rich, fully formed environment worth exploring again and again.

Bidwell is right. A single triennial can’t achieve this on its own. But the inaugural FRONT gives Cleveland what it has deserved for so long: another chance to be seen for what it truly is. What more could “An American City” ask for?