The year is 1977. Jimmy Carter is president, the first Star Wars movie has just been released, and New York’s art world is experiencing unprecedented change.

It was this year that four very determined women founded four major art institutions—the Drawing Center, the New Museum, the Public Art Fund, and Studio in a School—in New York City. Each organization, which celebrates its 40th anniversary this year, was born out its founders’ frustration with the status quo and their desire to fill a void left by the traditional art establishment. All four institutions continue to thrive today.

To piece together an oral history of these influential organizations’ early years, artnet News interviewed more than 10 figures from all four institutions and delved into the New Museum Digital Archive and its own oral history. The result is a snapshot of a moment in time when the art world was smaller, more experimental, and fully convinced of its ability to create lasting change.

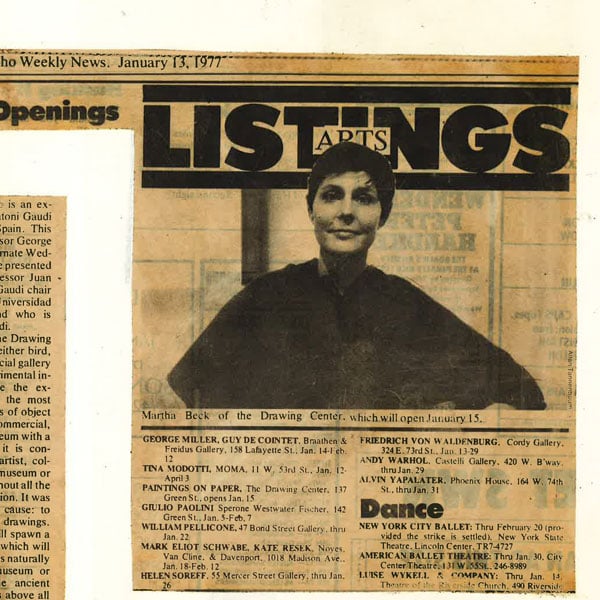

A January 1977 newspaper clipping announcing Martha Beck’s plans to open the Drawing Center. Courtesy of the Drawing Center.

In the Beginning

The Drawing Center

Martha Beck (1938–2014) had been the assistant curator of drawings at the Museum of Modern Art, but felt that the institution wasn’t taking drawing seriously as an art form in its own right. She applied for grants to open a museum dedicated to the medium, and the Drawing Center was born.

Brett Littman, Drawing Center executive director, 2007–present: Every time Martha pitched a show at the Museum of Modern Art, they said, “Great, we’ll put it in a closet on the second floor.” Drawing was secondary to painting and sculpture.

Dita Amory, Drawing Center board member, 1988–present: Martha wanted to give emerging artists an opportunity to show their drawings. There were no such opportunities in commercial galleries at the time.

The 1994 Kara Walker exhibition at the Drawing Center. Courtesy of the Drawing Center.

Frances Beatty Adler, Drawing Center board member, 1994–present: The Drawing Center really wanted to plant the flag for drawing as an independent and critically important medium. Drawing is the connective tissue between old and new and all different forms of art because everyone draws. Cave men drew, architects draw, kids draw, people doodle… it’s very accessible and palpable. We’ve shown Gaudi and Sol LeWitt. We’re the first institution that showed Kara Walker and William Kentridge.

Martha sensed the importance of drawing, and that artists wanted their drawings to be considered with the same attention as the other works that they made.

The first New Museum exhibition “Memory: at C Space” (1977), installation view. Inset: Marcia Tucker, the institution’s founding director (c. 1973–75). Photos courtesy of the New Museum.

The New Museum

Marcia Tucker (1940–2006) took the radical step of founding the New Museum, a non-collecting institution dedicated to living artists, after getting fired from the Whitney Museum of American Art, where she was curator of painting and sculpture. The critics had savaged her Richard Tuttle show, and the museum showed her the door. Within the year, she had set up shop with a new institution at the New School on 14th Street, in a space donated by trustee Vera List.

Allan Schwartzman, New Museum curator, 1977–80: Starting a museum was not commonly done, but somehow it seemed so natural and organic. The original mission was to provide a museum context for the work of truly contemporary artists who had not yet been embraced by the system.

In the 1960s and early ’70s, New York’s curators were deep in the trenches of art as it was being conceived. Marcia wanted that link, but was looking to provide an environment that had the professionalism and standards of care and insurance of an institution—an environment that looked and felt like a museum and produced catalogues and generated scholarship.

New Museum staff Marcia Tucker (back row upper left) clockwise; A.C. Bryson, Allan Schwartzman, Susan Logan, and Michiko Miyamoto. Photo courtesy of Warren Silverman/the New Museum.

Ellen Holtzman, New Museum managing director, 1988–92: That was always a question: “Why are you a museum and not just a space?”

That’s one of the things that Marcia held dear: the idea that it was a museum. Not that it be old and stuffy and everything in storage, but that it be a real, solid institution that’s going to be around for a really long time. It was going to be around for 100 years like the Met has been, and make that kind of contribution to the cultural scene, but programmatically doing what was new and exciting.

Schwartzman: Vera List was a great supporter. We started January 1, 1977, and by the summer she had secured us a space at the New School. I’m not saying money fell from the sky, but it was a compelling concept and there were enough collectors and others who funded culture to help pay the way.

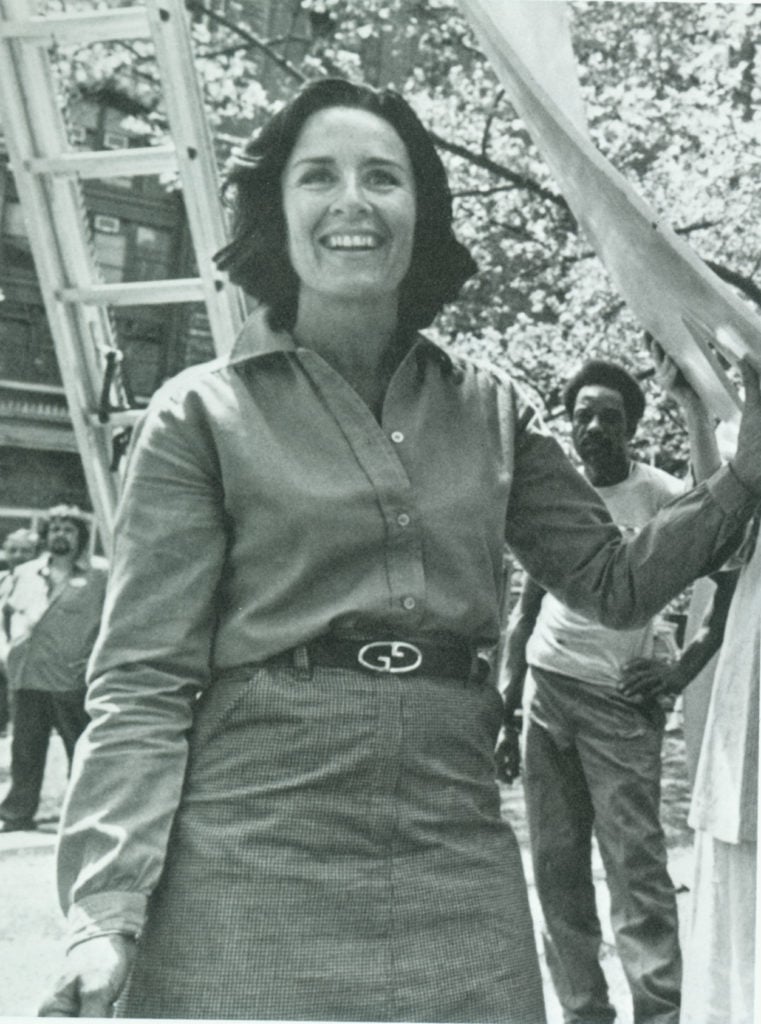

Doris C. Freedmand with Ed Koch at the opening of the first Public Art Fund exhibition, Ronald Blader’s Karma Sutra at what is now Doris C. Freedman Plaza in Central Park. Photo courtesy of Chuck de Laney/the Public Art Fund.

The Public Art Fund

In founding the Public Art Fund, Doris C. Freedman (1928–1981) saw an opportunity to bring public art to New Yorkers in a more sustained way. Ten years earlier, through the Department of Parks, Recreation, and Cultural Affairs, she had organized the city’s first large-scale outdoor public art exhibition, featuring work by artists including Louise Nevelson, Claes Oldenburg, and Tony Rosenthal. (The latter’s beloved Astor Place Cube became a permanent installation.) As president of both City Walls and the Public Arts Council, Freedman merged the two organizations to form the Public Art Fund, kicking off a new era of public art in New York.

Susan K. Freedman, Public Art Fund president, 1986–present, and daughter of founder Doris C. Freeman: My mother was a social worker by training. There has always been three sides to her vision for the organization. There’s this notion of giving artists an opportunity to show their work, there’s this notion of bringing art to audiences who would not normally be exposed to it in their everyday life, and there’s this notion of enhancing the quality of life in the city with artwork and how that changes your relationship to the city. She really believed in bringing museum-quality art to the public, and taking art out of the confines of the museums and galleries and into the street.

In 1977, my mother brought together two pioneering public art organizations. City Walls was created during the fiscal crisis, when sides of buildings were suddenly exposed when real estate slowed down. So what do you do? You bring in artists to make glorious murals on the sides of buildings that had become eyesores. The Public Arts Council [an offshoot of the Municipal Art Society] had been doing exhibitions with artists throughout the five boroughs. It made sense to unite them under one umbrella.

Artist Valerie Hammond, who still teaches with Studio in a School today, at PS 16 in Brooklyn (1985). Photo courtesy of Studio in a School.

Studio in a Schoolf

For Agnes Gund (1938–), Studio in a School was a necessary response to the city’s decision, prompted by the financial crisis, to cut school arts education budgets. Insistent on the value of an arts education, Gund set out to bring artists directly to schools, where they could engage with students, teaching them their craft.

Agnes Gund, Studio in a School founder: It was a 1976 article in the New York Times saying that they had decided to take all the schools, especially in the lower school, and stop all kinds of arts and gym and music and theater and dance programs. I just couldn’t believe that they wouldn’t still have an arts and music program at least available. Our whole idea was to have artists who were the teachers.

Tom Cahill, Studio in a School president, 1979–present: It was totally innovative, what Aggie had in mind. She created a program that had a new role for the artist. It would be a collaborative approach, creating professional working relationships, partnering with school administrators. She really, really believed that artists had something to say about art learning. She knew that artists also could really benefit from encounters with schools and working closely with communities.

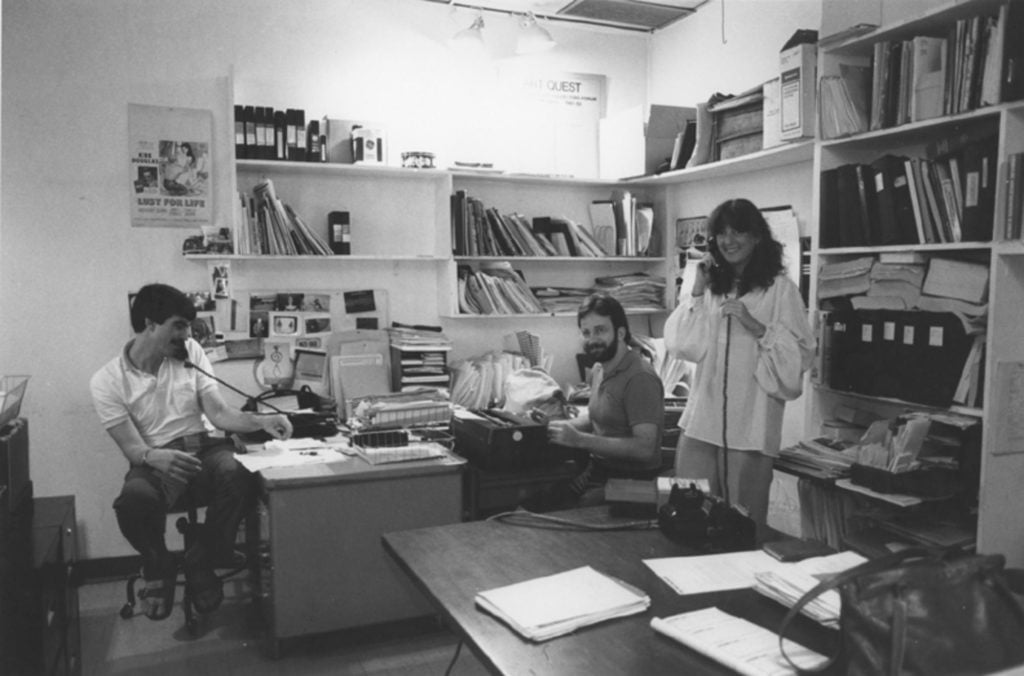

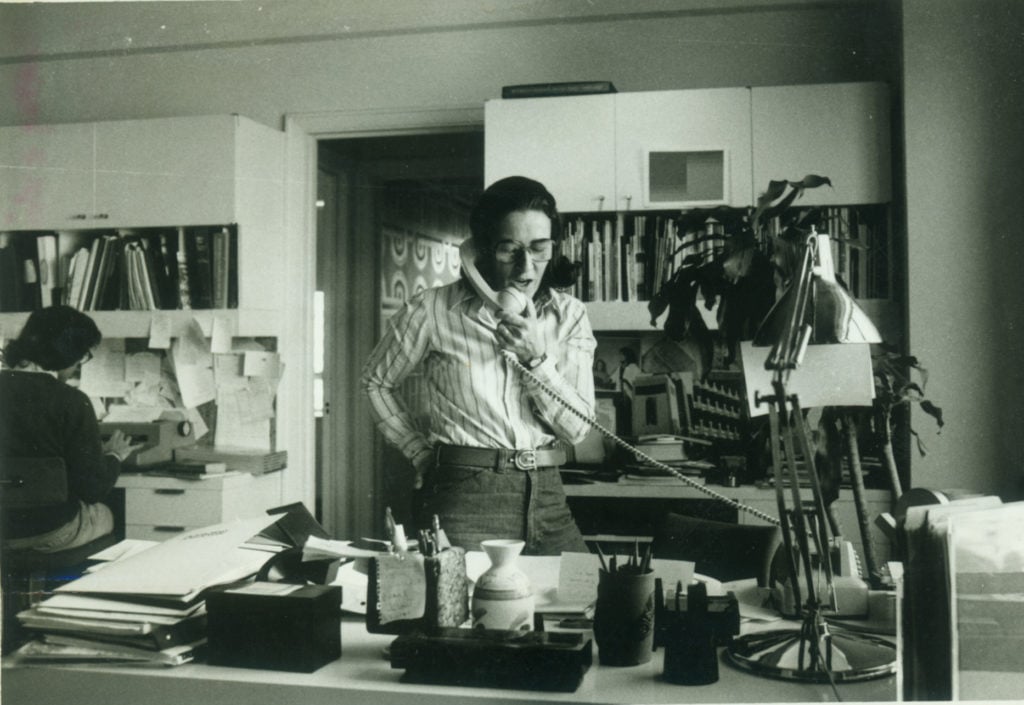

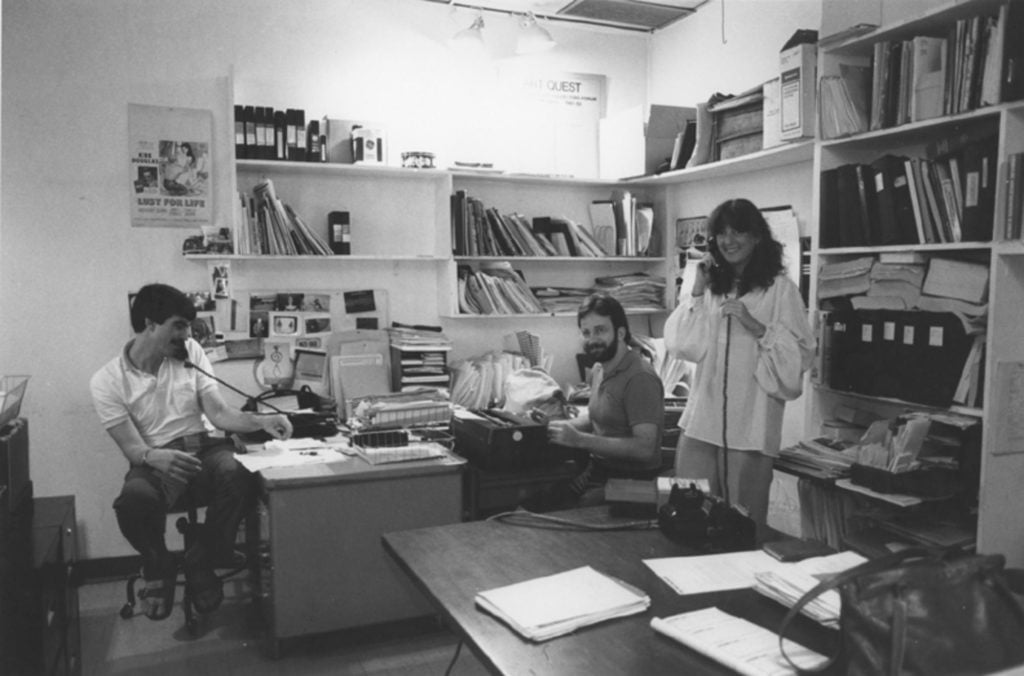

Johnson, Susan Logan, and Allan Schwartzman review slides at the New Museum (1978). Photo courtesy of the New Museum.

Why Were They All Founded in 1977?

Susan K. Freedman, Public Art Fund president: These organizations are all closely related to artists, and they’re all a reaction to the ’60s and what artists were feeling and thinking. The major museums were established, the buildings were built, so it was time for the alternative voices and spaces and moments.

Brett Littman, Drawing Center director: I think that there were some very visionary people at the New York State Council of the Arts who were very involved in a lot of the founding of these organizations. NYSCA had more money, the borough presidents at the time had more discretionary funds. The real estate market was fairly depressed, so you could find a cheap space in Brooklyn or Queens, or Chinatown or Soho. It was a much more viable time to start a nonprofit.

Allan Schwartzman, New Museum curator: The alternative space became the sanctuary through which artists could explore new ideas. They came into existence because there was a lot of empty space in Manhattan.

Dita Amory, Drawing Center board member: Soho was not what it is today. Rents were low. Buildings were primarily zoned for commercial use. And artists lived in the neighborhood.

Freedman: Everything is harder today. Some of the collectors who funded alternative spaces have chosen now to fund their own spaces. At this very moment in time, some are re-calibrating their priorities and are choosing to fund the ACLU, Planned Parenthood, which I totally agree with. There’s a lot of need out there. There also used to be a lot of corporate money in the arts, and now it’s all about marketing. There’s a lot of competition for not as many dollars.

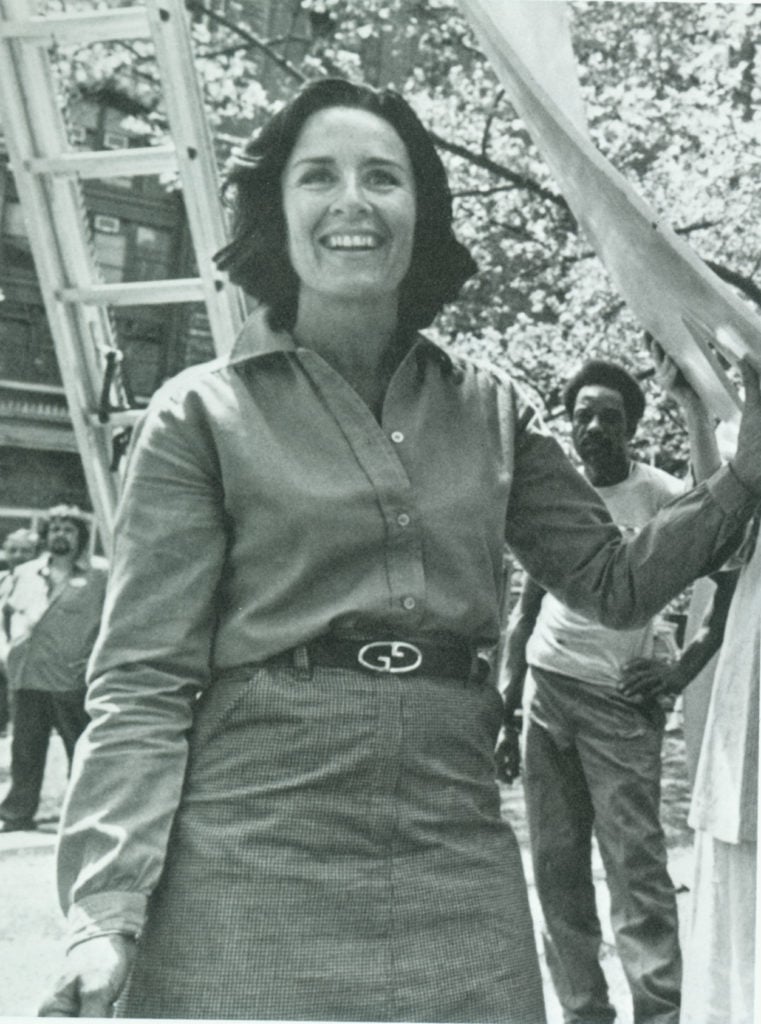

Doris C. Freedman. Photo courtesy of the Public Art Fund.

A Time for Women

Brett Littman, Drawing Center director: There were many women who were working in the art world who were quite visionary. You go down the list and every institution that just turned 40 had a female director. It was coming out of a burgeoning feminism. With the political and social climate, the time was right for women to take control, found their own institutions and set their own agendas. They had the wherewithal and the vision and the energy to do it.

Claire Gilman, Drawing Center, chief curator, 2010–present: There was a need for women to found their institutions, because maybe they weren’t going to get the top position at a larger institution.

Allan Schwartzman, New Museum curator: Is it because women are nurturers? Is it because they are less committed to the status quo and more open to challenging it? Is it because many of these women were empowered by the women’s movement? These were first generation feminists.

Anges Gund, Studio in a School founder: I think women have more of a feeling of the arts being important, not only their children’s education, but to their own education.

Jenny Dixon and Susan K. Freedman. Courtesy of the Public Art Fund.

Susan K. Freedman, Public Art Fund president: I think women get it. It makes perfect sense that my mother the social worker would then start the Public Art Fund! Aggie is the most giving person you will ever meet and she’s the most equitable person. Aggie was president of MoMA, so it’s not to say that these women were not comfortable, fluid, conversant in both worlds, but something resonated deeply them in this other world. There was this other [audience] out there that wasn’t being addressed.

Jenny Dixon, Public Art Fund, acting director and director, 1977–88: You have to realize that opportunities and jobs for women: there weren’t a lot of them. The arts, education, and nursing were always traditional places. And for ladies of a certain financial background, the arts were a place where they could excel. Each of them had some of their own resources. I think it was women of a certain ilk who really were engaged with art.

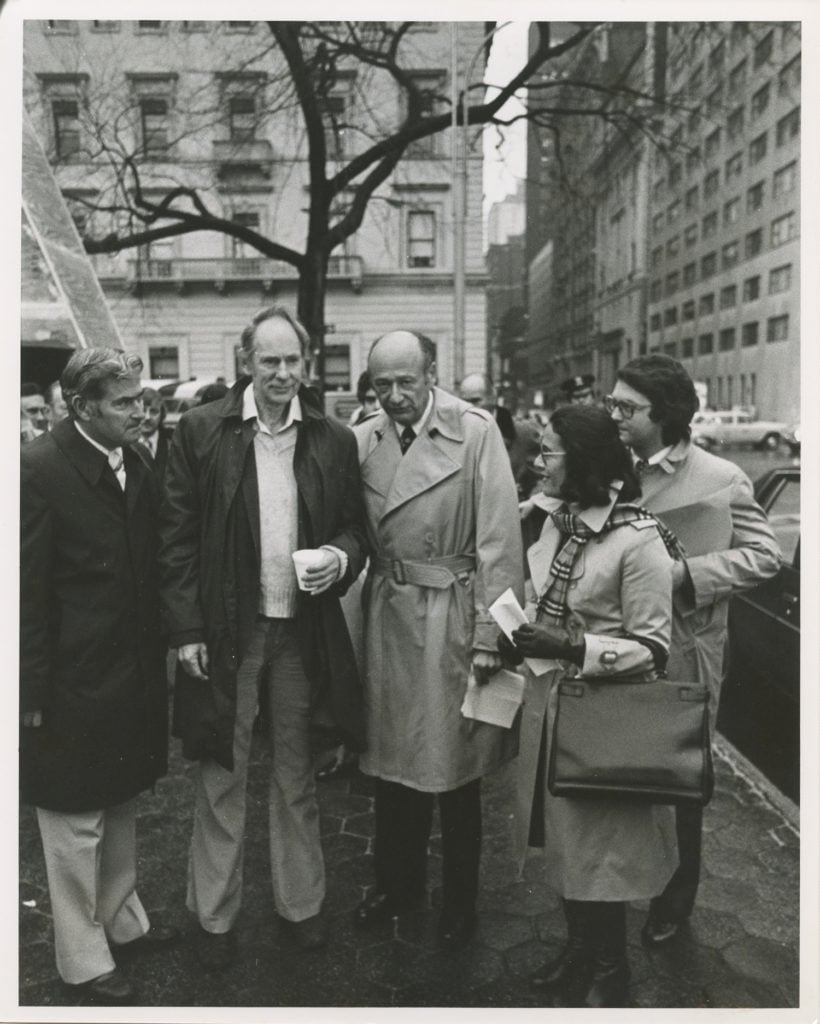

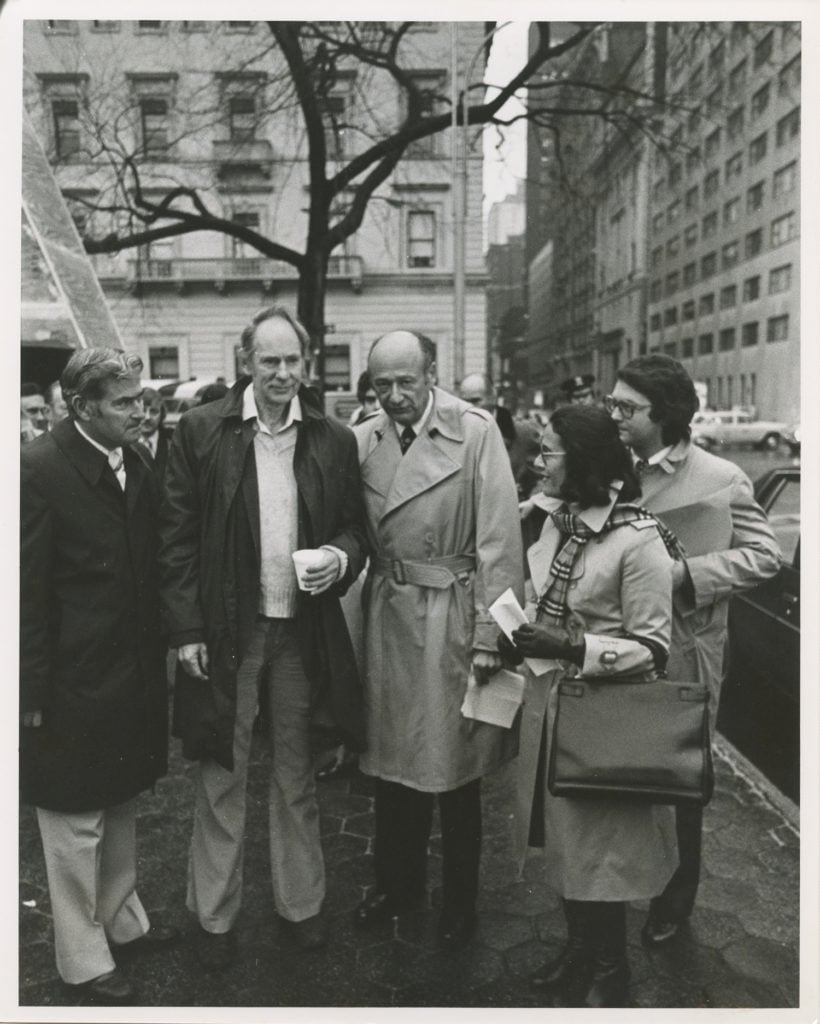

Marcia Tucker, John Jacobs, and Ned Rifkin at the New Museum (c. 1981). Photo courtesy of the New Museum.

Early Days at the New Museum

Allan Schwartzman, New Museum curator: I was in college studying art history. I decided to take a year off to explore whether it was a vocation or an avocation. I began working as a volunteer and then as a staff member at the Whitney. I was an assistant to a number of curators, including Marcia. After a few months, she was fired and decided she would create her own museum so she couldn’t lose her job again. She asked if I would leave with her. I was 19 years old. I was the first staff member.

I had the most extraordinary opportunity. I didn’t know anything about contemporary art when I started my job. I learned as we went along. Most people who got curator jobs had completed their thesis. I just kind of walked in. I was at the right place at the right time.

Lynn Gumpert, New Museum curator and senior curator, 1980–88: When I first arrived in New York in ’77, I spoke with a woman who, I think, at the time was working for Pace Gallery. And she mentioned to me, “Oh, you know, Marcia Tucker has just started this museum, but she’s only working with volunteers.” It was exciting, but I needed a paying job!

Schwartzman: Marcia was a very charismatic person. As her previous assistant told me, she could get somebody to spend a day standing in a corner tying their body into a form of a pretzel, convinced they were doing it for the good of the cause. She had several collector patrons who were benefactors of the Whitney who provided the early grants.

Gumpert: We always talked a lot about politics and diversity. Marcia was very, very concerned with this notion early on, far ahead of most people, which was pretty remarkable. And we just wanted to have a forum where more and different kinds of people could exhibit their work, so we were always open to looking at that issue. Everybody on the staff bought into that idea and felt that it made sense.

Rusell Ferguson, New Museum librarian and special projects editor, 1986–91: Marcia was very sincerely committed to the idea that everyone had a say. We would have staff meetings with every single member of staff, and everyone was able to weigh in and say what they thought about everything. And Marcia genuinely wanted to hear that. But, on the other hand, it was her museum. She had opened it, she’d put her whole life into it, and completely understandably, I don’t think she was going to do anything that she didn’t actually want the museum to be doing. So there was a slight sense that we all had to agree, in theory, that it was totally democratic. But I think everyone also knew that Marcia was the director of the museum. There were a few idealistic people who really expected it to be a kind of worker’s commune, which it was not.

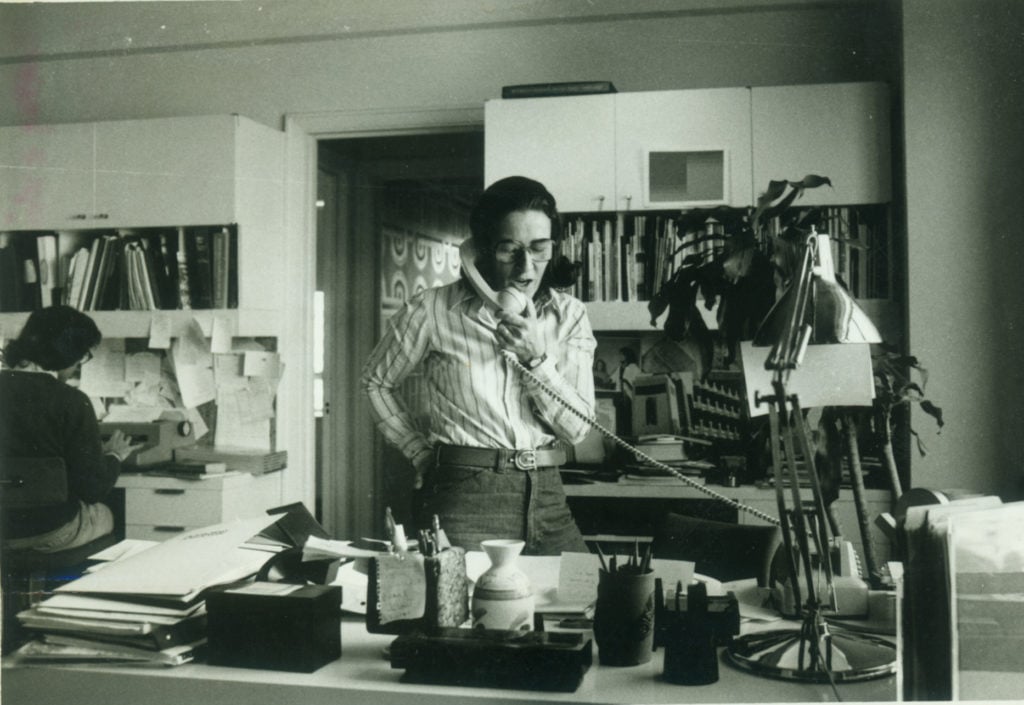

Doris C. Freedman in her office. Courtesy of the Public Art Fund.

A Dramatic Start for the Public Art Fund

Jenny Dixon, Public Art Fund, acting director and director: I was living down in the South Street Seaport, and I had studied art. I had broken up with my boyfriend and my friends from college wanted nothing to with me.

I became Doris Freedman’s assistant. It was before Public Art Fund. “Doris Freedman’s office”—that’s how we answered the phone.

Doris was an extraordinary, marvelous woman. There was never a sense that you couldn’t do anything. She went into the hospital and she told me she had a premonition that she wasn’t going to come out. [Doris Freedman died in November 1981, after being in a coma since August 1979.] She handed me the mantle. I was there at its inception, taking her ideas and moving them forward.

I’ve watched history be changed, but the fact is she wasn’t there. But Doris would be so proud to see what has become of the organization she envisioned.

Agnes Denes, Wheatfield–A Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill (1982), New York, commissioned by Public Art Fund. Photo courtesy of John McGrail.

Susan K. Freedman, Public Art Fund president: In retrospect, the Public Art Fund was an inherently confusing name, because it implied that there was a fund that existed and it made it very complicated to raise money!

Dixon: One of the things we were really lucky about, we had free rent and free utilities in a building Doris’s family owned on Central Park West. Overhead wasn’t as much of a problem. She was very clever and resourceful in finding opportunities where the private sector would pay for things. We would work with different galleries and they would loan us work, often very much in their own interest.

Freedman: It was about enhancing the quality of life in the city. It’s one thing to be the art capital of the world because we have these extraordinary institutions. It’s another to have a museum in the street, to experience four man-made waterfalls by Olafur Eliasson, to have The Gates in Central Park by Christo, to have these extraordinary and unexpected public events. We created a city of 8 million art critics.

Students working at PS 112 in Manhattan with Cathy Ramey, who has worked with Studio in a School for over 20 years. Photo courtesy of Studio in a School ©Mindy Best.

Finding Footing at Studio in a School

Tom Cahill, Studio in a School president: Studio was initially funded with just with the support of Aggie’s private foundation. It was a challenge getting other organizations to join in. I think we sent out 40 proposals and I don’t think we got one yes.

Agnes Gund, Studio in a School founder: After two years, we said, “We have to get a director.” We had a number of people interested in the job and after much deliberation we decided to ask Tom. That was the best thing we ever did for the program, because he has been amazing.

Cahill: The artists were really impressed with what the kids could do the classroom, and the teachers were happy that the kids were learning. You could see kids’ voices, you could see their creative work, and you began to realize art was so connected to learning.

Gund: We gave the schools the opportunity to pick an artist. From three sites, we moved to six, and then it kind of multiplied. We were really able to learn from the school administrators, the artists, the students, about what made the program a success. We began to be recognized by people as serious teachers of art, not just hand turkeys at Thanksgiving.

The inaugural exhibition at the Drawing Center, “Paintings on Paper,” featuring

James Bishop, Ralph Humphrey, Robert Mangold, Dorothea Rockburne, Robert Ryman, and Douglas Sanderson. Courtesy of the Drawing Center.

Standing Out at the Drawing Center

Frances Beatty Adler, Drawing Center board member: The challenge for a serious small institution is always getting support. I remember when we had a benefit and we were honoring Richard Serra, who is a notorious curmudgeon. He actually came, and he started saying, “The art world can be a smarmy, terrible place, but the Drawing Center”—and then everyone held their breath—“but the Drawing Center represents the very best of the art world.”

Brett Littman, executive director: I came to the Drawing Center in 1982 when I was in high school. I remember hiking up to the fifth floor. I feel like I’m the grandson of the alternative space movement. Every organization I’ve worked at was started in 1976 or 1977! [Littman previously worked at Brooklyn’s UrbanGlass, founded in 1977; and Queen’s MoMA PS1 and Brooklyn’s Dieu Donné, both founded in 1976.]

Beatty Adler: We’ve shown drawings from tattoos and by the Plains Indians. The program has always surprised people. What we do seems to be kind of original, in many instances, and very forward thinking.

We also had this viewing program where an artist would bring his work and a curator would come and give him advice. People from the MoMA would come look at the things that we had chosen from the contemporary artists who had never exhibited in New York.

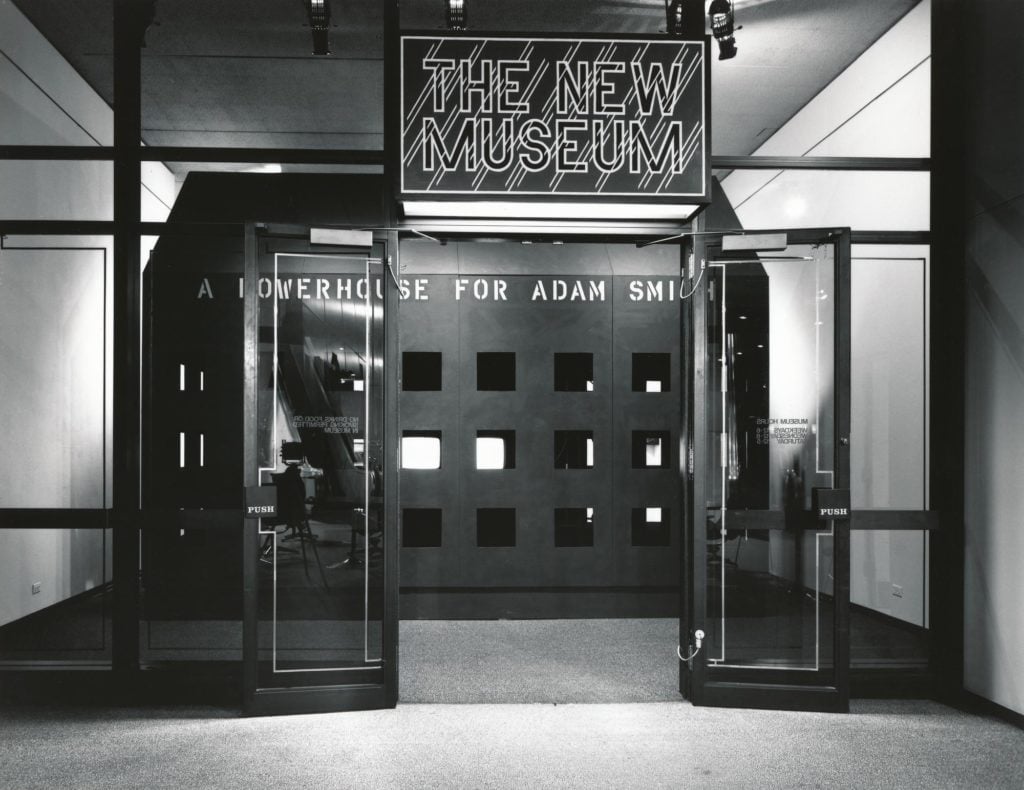

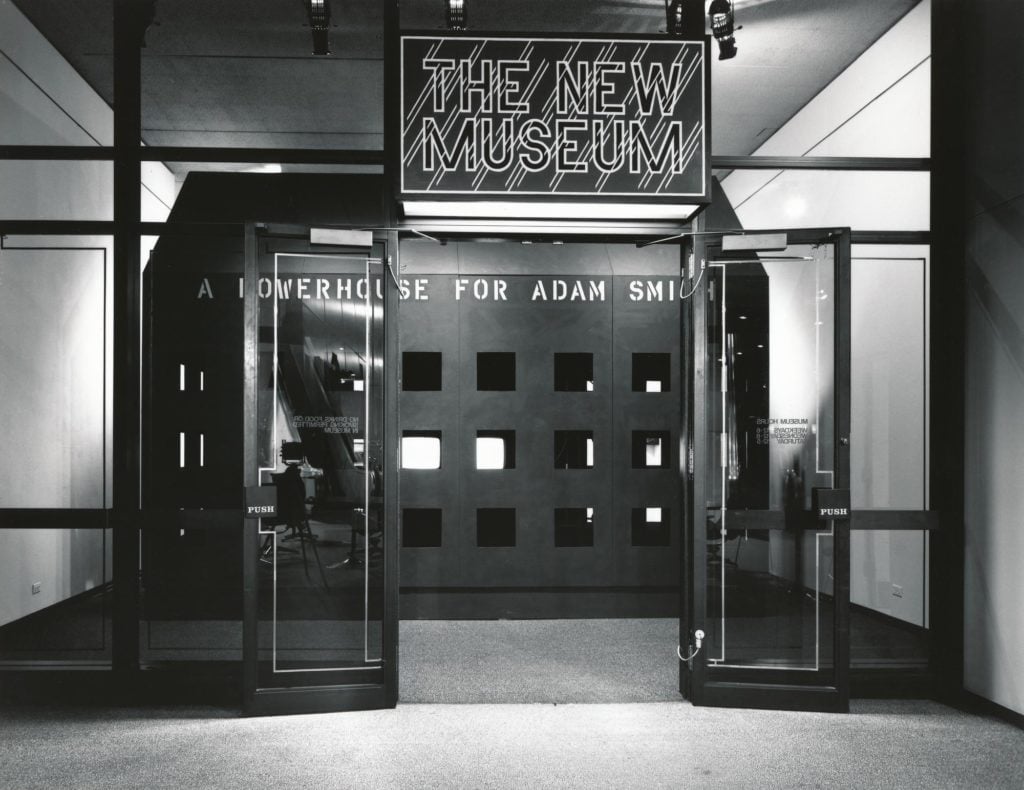

New Museum entrance during “Investigations: Probe, Structure, Analysis,” Lauren Ewing, A Powerhouse for Adam Smith (1980), installation view. Photo courtesy of David Lubarsky/the New Museum.

A Time for Experimentation—and Struggle

Ellen Holtzman, New Museum managing director: There was this dichotomy between being an institutionalized force, a presence, a cultural institution in New York, and still being nimble, flexible, and all of those things. And they were successful, but it was always a struggle. There was never enough space, and there was never enough money.

I left because of financial reasons. We were budgeting and things were tight. I don’t remember the numbers, but we were cutting positions. I was responsible for having to cut certain positions. And—it was just difficult and I wrote my position out of the budget.

Susan Freedman, Public Art Fund president: For [Eliasson’s] New York City Waterfalls, I think we had to go to 50 total agencies at the city, state, and federal levels. There was environmental protection and layers upon layers of bureaucracy. It’s easier to say no, but Mayor Bloomberg believed in them. There was person in City Hall who was advocating and behind you 100 percent, who knew what these project meant for the soul of the city, and for economics—I don’t think the arts are the same priority for de Blasio, but he’s been very supportive of the Ai Weiwei [project].

“Erika Rothenberg: Have You Attacked America Today?” (1989). Photo courtesy of the New Museum.

Holtzman: There was the show, “Have You Attacked America Today?” [It was] a small window show, in 1989, by Erika Rothenberg. And we were in that moment of controversy—not for the sake of controversy, but because there were things to say that some aspects of the world didn’t want to hear.…

During the Rothenberg piece, the window was smashed with a garbage can three times, I believe. That kind of vandalism was new—new to me, and I think it was new to Marcia.

Rusell Ferguson, New Museum librarian and special projects editor: I remember coming back to my office, and my desk wasn’t there, and discovering that Adrian Piper had taken it to install the piece where the desk is turned up against the wall—Cornered [1990], I think it was called. I didn’t have a desk and didn’t figure out a way to get that back.

Jane Dickson, an artist working for the Spectacolor Light Board in Times Square, made the Public Art Fund’s “Messages to the Public” series possible. Nan Goldin took this photo of Dickson in Times Square. Photo courtesy of Jane Dickson.

Making History

Jenny Dixon, Public Art Fund, acting director and director: One of the early successes was “Messages to the Public.” The artist Jane Dickson was working for the Spectacolor electronic billboard, and convinced the owner to turn over the board to an artist for a week at the end of every month for a minute every hour.

Jane Dickson, Spectacolor employee who created the Public Art Fund’s “Messages to the Public”: I said, “I will make this happen if I can pick the artists for the first year. I want to give this opportunity to my young friends, not to famous old guys.”

We sat at these huge computers behind the sign. It was before floppy discs had been invented, let alone hard drives. Animation takes a lot of memory! There were no user programs yet, and there were no digital typefaces. I spent a lot of my time trying to approximate a lot of typefaces digitally.

Keith Haring, Untitled(1982), one of the first works for “Messages for the Public.” Photo courtesy of the Public Art Fund.

I thought, “What artists do I know whose art will translate well into this crude graphic media?” We did Keith Haring, David Hammons, and Jenny Holzer, who was doing paper cups at the time… I also had proposed Nancy Spero and Barbara Kruger and they both made pro-choice works. It turned out my boss was an ardent Catholic, and he vetoed it. Then he insisted on a right to life piece. I said, “Let’s do the 10 artists we want and this really crappy fetus piece!” Starting in January 1982, we had one artist a month.

Alfredo Jaar, Public Art Fund, “Messages to the Public” artist, 1987: I never knew why I got invited or who suggested my name. I wouldn’t dare approach anyone! I was completely unknown, and they approached me.

The potential of a larger audience was enormous. We had calculated that more than a million people could see the work. I was interested in expanding the audience beyond the art scene, which is very insular.

Alfredo Jaar, A Logo for America (1987), Times Square. Photo: courtesy Alfredo Jaar.

I made A Logo for America because I had been shocked to discover that people were saying “America” referring to the US and not the entire continent. They were erasing North America and South America. That use of the word American is absolutely wrong—those of us born in Latin America are absolutely Americans. It was really upsetting to realize the geopolitical reality of the domination of the United States of the rest of the continent.

Dickson: I treated the artists like clients, like Coca Cola’s art director. I would show them a few ads so they could see what the sign was capable of.

Jaar: [Doing the piece] was absolutely fantastic. It gave me a different kind of platform. I would say that the art world didn’t respond at all, but it’s my most reproduced work today. It had this life of its own. It’s in school books for children. In 2014, it was shown again in Times Square on 65 screens.

Dickson: I quit in the beginning of 1983. They wanted to promote me to be the art director [of Spectacolor]. I thought, “I am going to make money and I’m not going to make art.” I chose painting because I like getting my hands dirty. [But] I am extremely proud of that project. It was much more groundbreaking than we had any idea at the time.

Parking lot at 235 Bowery, now home to the New Museum (c. 2004). Courtesy of the New Museum.

Lasting Legacies

Claire Gilman, Drawing Center, chief curator: We have grown and evolved in certain ways, but also stood our ground. Every institution is constantly expanding. We have not gone that route. We have stood by that kind of intimacy, small-scale Drawing Center since the beginning.

Brett Littman, executive director: The Drawing Center is in early middle age, so it’s a good moment to reevaluate what its core values are. But drawing isn’t in any danger of extinction. It’s never been plagued by that question the way that painting has.

Susan Freedman, Public Art Fund president: Over the last 40 years, we’ve become known as the organization to do the impossible or unimaginable—to flood a disused portion of subway track on Canal Street and put gondolas in it. It is really exciting to see people turn a corner and look up and go, “Wow, what is that?” But we have a sacred responsibility. People aren’t choosing to see these artworks, so you have to be really careful, sensitive, and respectful. There’s a public trust that you have to live up to.

Students working at Studio in a School. Photo courtesy of Studio in a School ©Mindy Best.

Agnes Gund, Studio in a School founder: We’re have over 200 operations and we’ve moved beyond schools. Some are homeless shelters; some are daycare centers. We do portfolio classes on Saturdays for high school students applying to college. Our kids make it into schools like Pratt, SVA, or Cooper Hewitt, and we offer some partial scholarships. And we started the Studio Institute, which is in Philadelphia, Boston, and Cleveland with internships for high school and college students.

Littman: There hasn’t been a time since then [1977] that there have been so many nonprofits founded that have lasted as long as they have. Whatever it was in the air, the zeitgeist, I hope we get that back at some point, because it was powerful.

Interviews have been condensed and edited.