Law & Politics

Orlando Museum’s Ex-Director Who Was Ousted Over Fake Basquiats Fires Back

In a fiery countersuit, Aaron De Groft insists the forged paintings seized by the FBI are the real deal.

In a fiery countersuit, Aaron De Groft insists the forged paintings seized by the FBI are the real deal.

Sarah Cascone

Ousted Orlando Museum of Art (OMA) director Aaron De Groft has countersued the institution, alleging he was made into a scapegoat after the FBI infamously seized 25 Jean-Michel Basquiat paintings it believed to be forgeries from a high-profile exhibition. De Groft’s Basquiat countersuit still maintains that the works are the real deal.

“I am ready to talk and going to war to get my good name back, my professional standing, and personal and professional exoneration,” De Groft wrote in an email to me, sharing his counterclaim.

In a subsequent phone call, De Groft was steadfast in his belief in the paintings’ authenticity, and denied the museum’s allegations that he had any ulterior financial motives in bringing the suspect works to Orlando.

That De Groft still has faith that these are Basquiats is surprising. A Los Angeles auctioneer named Michael Barzman has confessed to forging the paintings rather than buying them at an auction of an abandoned storage locker.

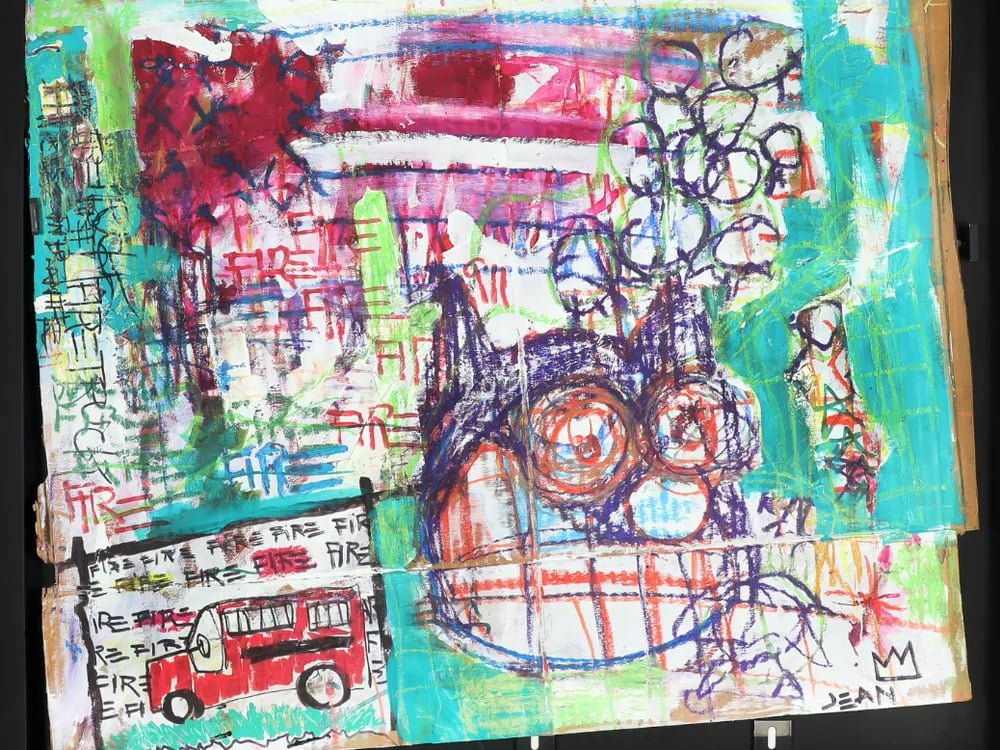

A fake Jean-Michel Basquiat the FBI seized from the Orlando Museum of Art. Michael Barzman has confessed to creating the forgeries, and will pay a $500 fine and serve three years probation for making false statements to the FBI about the forgeries. Photo courtesy of the United States Attorney’s Office Central District of California.

The original owner of said storage locker was the late Hollywood screenwriter Thad Mumford, who purportedly met Basquiat while the artist was in Los Angeles in 1982 for a Gagosian show. But Mumford signed an FBI affidavit stating that “at no time in the 1980s or at any other time did I meet with Jean-Michel Basquiat, and at no time did I acquire or purchase any paintings by him.”

Nevertheless, De Groft’s countersuit—he is representing himself pro se—insists that he “was given no opportunity to present all the favorable evidence demonstrating [the paintings’] authenticity. That proof is ironclad.”

Both Barzman and Mumford were lying, according to De Groft. He believes that Mumford really knew Basquiat and purchased his works, but denied it to the FBI because he had illegally failed to disclose his valuable painting collection when he declared bankruptcy in 2008.

Barzman pleaded guilty not to fraud and forgery, but to lying to the FBI about the works’ origins. He was sentenced to just three years probation and a $500 fine. De Groft believes Barzman did purchase Mumford’s storage locker, and that it did contain 25 Basquiat paintings.

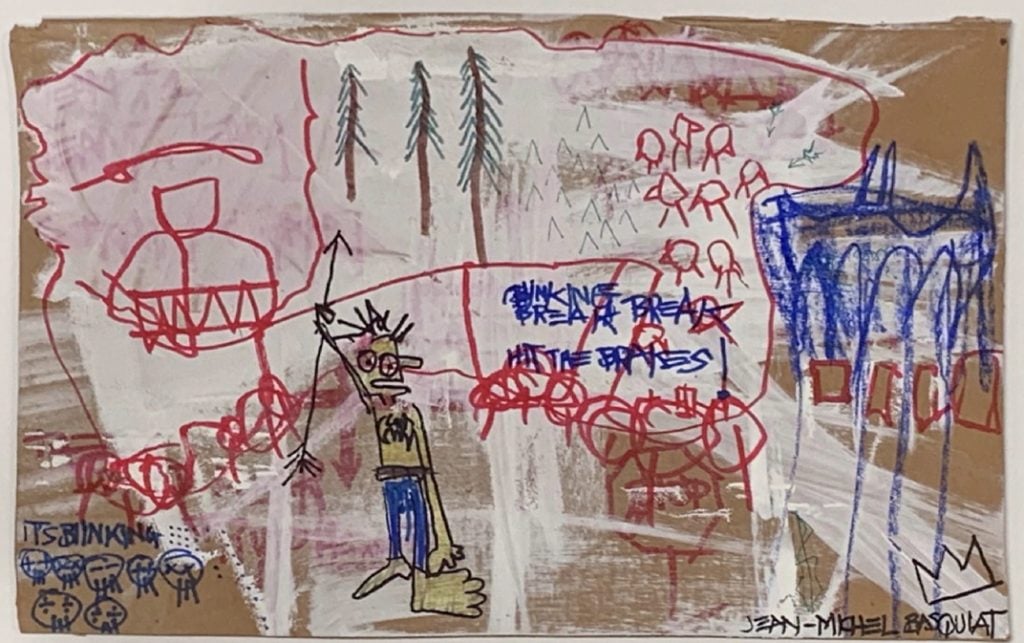

Snapshot of an alleged Basquiat image featured on the Orlando Museum of Art’s website on June 19, 2022. Procured via the Wayback Machine.

According to De Groft, Barzman and his alleged forgery accomplice, J.F. did make nine additional fakes, but they sold those to Jonas Leborg, an art dealer in Oslo, Norway, not to William Force, Leo Mangansell, and Pierce O’Donnell, the three owners involved in the Basquiat show.

The Oslo paintings “are absolutely pitiful,” De Groft insisted. His theory is that the FBI pressured Barzman into claiming to have forged all the storage locker paintings as part of a generous plea deal.

Ahead of Barzman’s sentencing, O’Donnell, who is a lawyer, filed a victim impact statement attempting to prove that the auctioneer had falsely claimed authorship of the paintings in a “blatant attempt to destroy the 25 Basquiats.” He found it preposterous that anyone believed the confession.

“Barzman was a storage locker scrounger and J.F was a nightclub bouncer who reportedly sells Christmas trees for a living. Neither has any known education, training, or experience as an artist—much less one of the talent who could paint convincing Basquiat forgeries in five to 30 minutes as Barzman claims,” the statement said.

A fake Jean-Michel Basquiat the FBI seized from the Orlando Museum of Art. Michael Barzman has confessed to creating the forgeries, and will pay a $500 fine and serve three years probation for making false statements to the FBI about the forgeries. Photo courtesy of the United States Attorney’s Office Central District of California.

There was a time when the ill-fated Basquiat exhibition, “Heroes and Monsters,” seemed poised to take the OMA to the next level. De Groft organized the show shortly after taking up the director post in early 2021, promising the board that the trove of previously unseen early works by the famed street artist would be a surefire blockbuster.

“I was tasked to invigorate the museum in advance of its 100th anniversary,” he said. “That’s what I did.”

“[De Groft] did his job professionally and in good faith, created a spectacular exhibition that garnered rave reviews, set attendance records, made a substantial profit, and is not deserving of the obloquy heaped upon him,” his countersuit claimed.

But shortly after “Heroes and Monsters” opened in early 2022, the New York Times published an article questioning their authenticity. The FBI, it turned out, had already been investigating the case, but De Groft had still gone ahead and opened the show. In June, it all came crashing down, with authorities dramatically stripping paintings from the galleries’ walls during visitor hours.

“They stormed the museum with helicopters and all kinds of stuff,” De Groft recalled.

The fallout was immediate.

Installation view of the “Heroes & Monsters: Jean-Michel Basquiat, The Thaddeus Mumford, Jr. Venice Collection” at the Orlando Museum of Art, 2022. Photo courtesy of the OMA.

“The value of our paintings was totally destroyed. No one would purchase them, and no museum or art gallery would exhibit them,” O’Donnell wrote in his victim impact statement. “They might as well have been consumed by a fire. It is no exaggeration that if the art world had a Hall of Shame, our paintings would be permanently enshrined there.”

Following the raid, the museum fired De Groft. This August, it followed up with a lawsuit against the former director and three owners of the so-called Basquiat works, seeking to hold them accountable for “knowingly misrepresented the works’ authenticity and provenance.”

Further, it accused De Groft of having a financial interest in the works, and of trying to help the owners sell the collection for a substantial commission.

“Nothing could be further from the truth,” De Groft countered in his filing with Florida Circuit Court, citing his 35-year museum career and three art history degrees as evidence of his trustworthiness. “Until [the museum] illegally terminated him and orchestrated a concert campaign to destroy him, defendant had a stellar reputation among his peers.”

The OMA’s complaint accused the paintings’ owners of “promising De Groft a significant cut of the proceeds of the anticipated multimillion-dollar sale. De Groft quickly jettisoned his professional, ethical, and fiduciary duties to OMA and agreed to exhibit the paintings before ever seeing them in person.”

“This wild allegation is the product of OMA’s desperation to point the finger at others and to deflect public and media attention away from it,” the countersuit stated. “OMA has absolutely no evidence to support its outrageous allegations.”

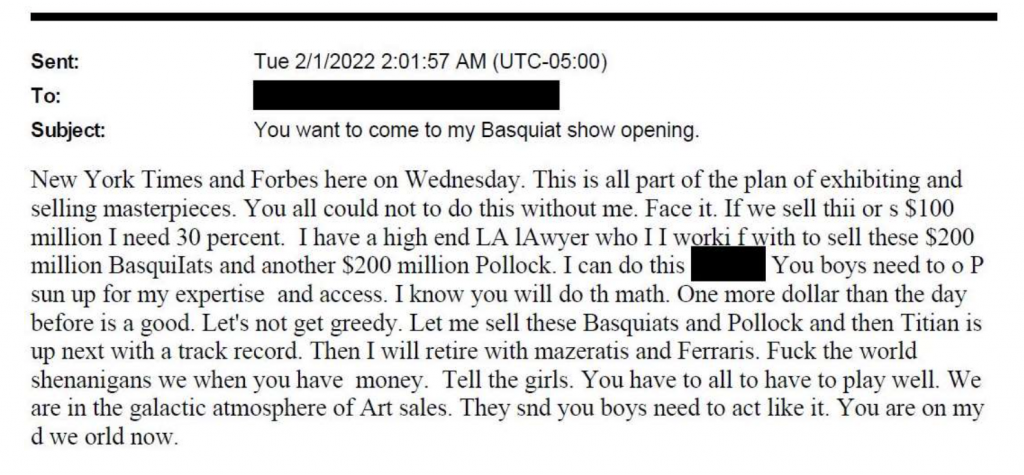

But the OMA complaint appears to present compelling evidence that De Groft believed he stood to benefit financially if the exhibition helped secure a buyer for the collection. “I have a high end LA lAwyer who I I worki f with to sell these $200 million BasquiIats,” the director wrote in an email riddled with typos. “Then I will retire with mazeratis and Ferraris.”

When asked about this and other emails, De Groft told me: “I don’t recall writing that.” He added that “I don’t know who wrote them because [Akerman, the OMA’s law firm] had access to my private email” after a 2021 FBI subpoena.

An email from former Orlando Museum of Art director Aaron De Groft including the museum’s complaint against him.

De Groff’s new filing also maintains that the OMA and its board was more than happy to present the so-called Basquiat paintings, even after doubts began to arise as to their authenticity.

OMA’s initial complaint accused De Groft of failing to inform its board of the FBI investigation. But the countersuit contends that when the FBI issued a subpoena regarding the works, he immediately went to then-OMA board of trustees chair Cynthia Brumback. It was allegedly at her instruction the board was kept in what the initial complaint described as “completely in the dark about such an extraordinary, unprecedented, and dangerous situation.”

Instead, Brumback hired a law firm, Akerman, who “conducted their own due diligence about the 25 paintings” and “found nothing warranting canceling the exhibition,” according to the countersuit. It also noted that “the FBI told [De Groft] there was no reason to pull the plug on the exhibition. These two statements fortified Defendant’s belief that the 25 paintings were authentic Basquiats.”

“Everybody says ‘oh, you should have known what was up.’ But we had no idea,” De Grof insisted. “The FBI told me and the board chair directly that we were not under investigation, nor was the museum. They would not tell us what they were looking for.”

His countersuit calls for Akerman to recuse itself from the lawsuit due to its earlier involvement in the investigation. Under Florida ethics laws, lawyers cannot represent a part in a case if they are also witnesses to the issue at hand. (The firm had not responded to inquiries as of press time.)

Installation view of the “Heroes & Monsters: Jean-Michel Basquiat, The Thaddeus Mumford, Jr. Venice Collection” at the Orlando Museum of Art, 2022. Photo courtesy of the OMA.

By the time the OMA show opened, there was also material evidence that the works weren’t what they claimed to be. One of the cardboard boxes had FedEx labeling in a typeface that experts claim wouldn’t be introduced until 1994.

And there was an obscured address on the back of another painting for Barzman’s L.A. apartment. At the time the piece was said to have been created, Barzman would have been just four years old, and living across the country.

De Groft offered an explanation for both issues. He disagrees that the FedEx box, which features purple text reading “align top of FedEx shipping label here,” is printed in Universe 67 Condensed Bold, the supposedly anachronistic font, citing “two forensics reports of people that studied typography.”

And he claims that the storage locker company affixed the label with Barzman’s address on it to the painting after the auction to mail it to him, after having nearly thrown out the bundle of cardboard works.

“[De Groft’s] conclusion that the 25 Basquiats are authentic will be proven at trial, thereby dealing a much-deserved, fatal blow to OMA’s lawsuit and exposing plaintiff to tens of millions of dollars for its outrageous treatment of [De Groft] and deliberately trashing his excellent reputation,” the countersuit concluded. “Acts have consequences, and intentionally malicious acts are punished harshly. An Orlando jury will teach OMA a lesson that it will never forget.”

More Trending Stories:

Conservators Find a ‘Monstrous Figure’ Hidden in an 18th-Century Joshua Reynolds Painting

A First-Class Dinner Menu Salvaged From the Titanic Makes Waves at Auction

The Louvre Seeks Donations to Stop an American Museum From Acquiring a French Masterpiece

Meet the Woman Behind ‘Weird Medieval Guys,’ the Internet Hit Mining Odd Art From the Middle Ages

A Golden Rothko Shines at Christie’s as Passion for Abstract Expressionism Endures

Agnes Martin Is the Quiet Star of the New York Sales. Here’s Why $18.7 Million Is Still a Bargain

Mega Collector Joseph Lau Shoots Down Rumors That His Wife Lost Him Billions in Bad Investments