Archaeology & History

A Woman’s Name Uncovered in the Margins of a 1,200-Year-Old Medieval Manuscript Provides a Fresh Clue About Its Real Significance

The discovery is a rare example of the involvement of women in medieval book culture.

The discovery is a rare example of the involvement of women in medieval book culture.

Richard Whiddington

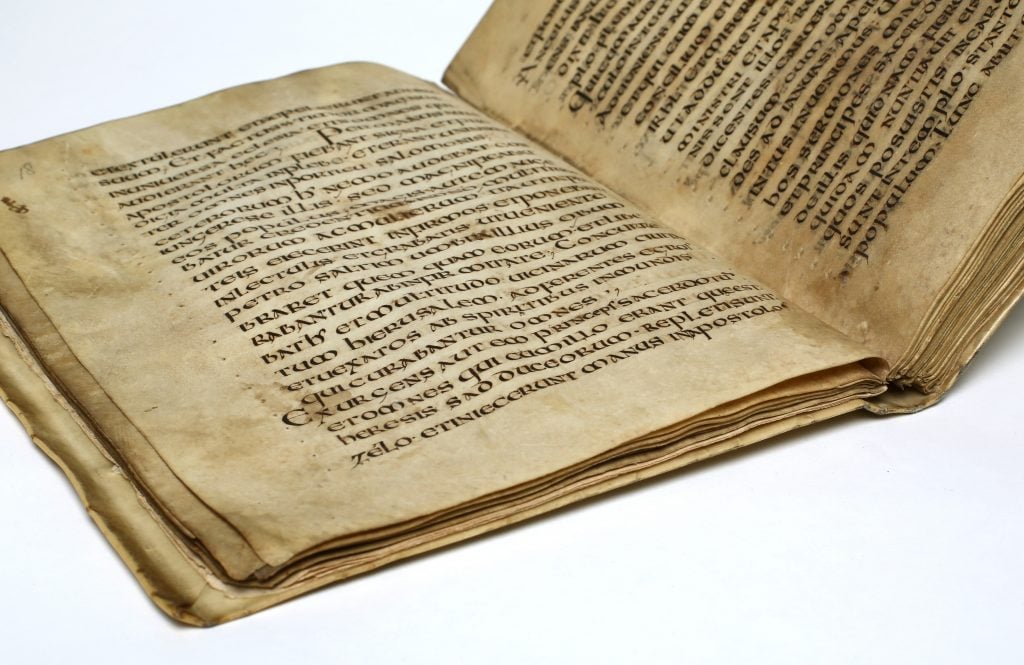

While studying a rare medieval manuscript in Oxford’s Weston Library, PhD student Jessica Hodgkinson noticed something unusual: a series of small, barely visible indentations at the bottom of page 18. Together, the marks spelled out the name Eadburg, the abbess of a female religious community in Kent during the 8th-century.

The inscriptions, which state-of-the-art 3D recording technology discovered a further 14 times in one form or another throughout the volume, is rare evidence of women in medieval England owning, using, or creating manuscripts. So began Hodgkinson’s detective work into a highly educated woman who lived 1,200 years ago.

“My thesis seeks to explore the active participation of women in book culture in early medieval Western Europe through analysis of the surviving manuscripts,” Hodgkinson told Artnet News, noting the scarcity of such works in early medieval England. “These manuscripts can tell us a lot about how noblewomen engaged in literate culture and networks of exchange.”

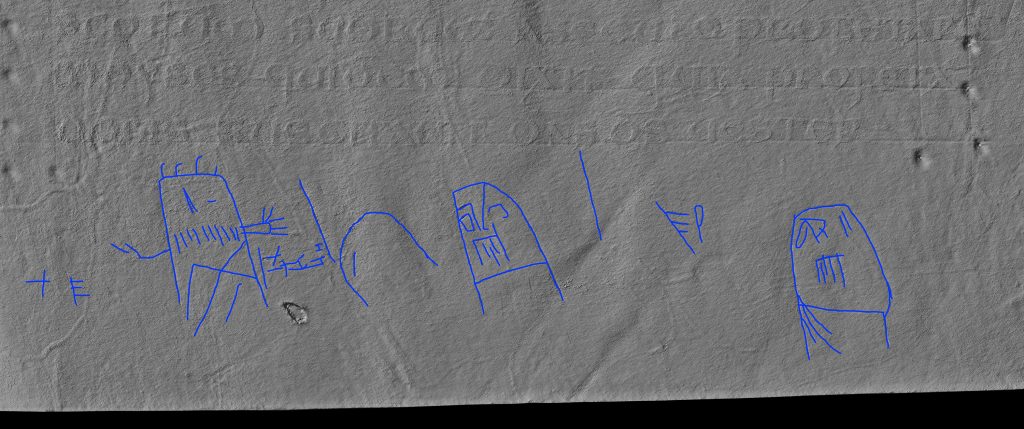

Image showing the digital annotation applied at the exact position where it was recorded. Photo: courtesy University of Leicester.

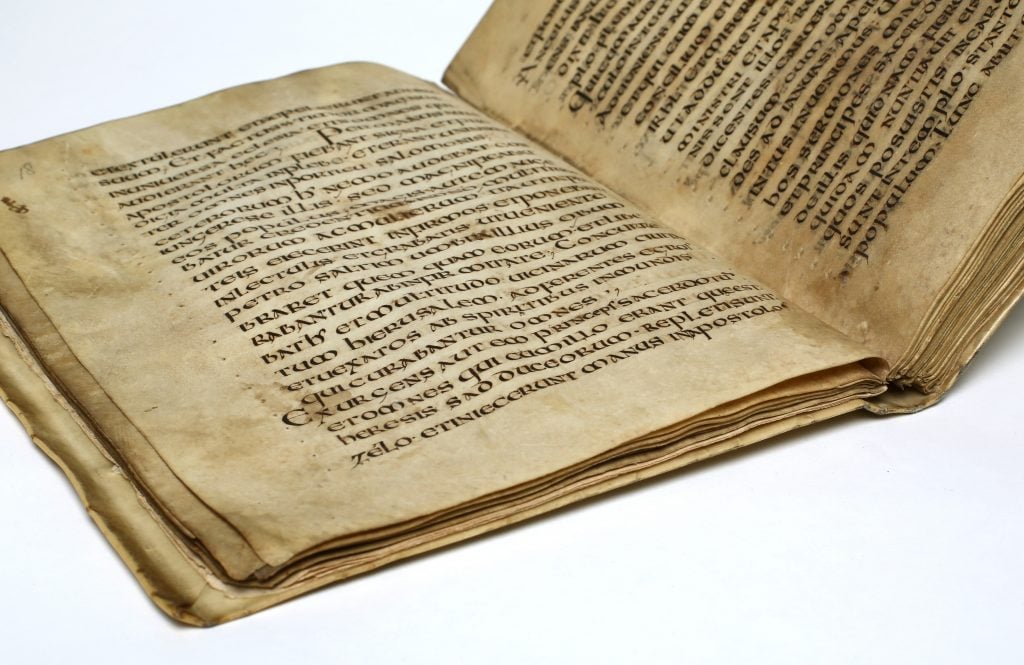

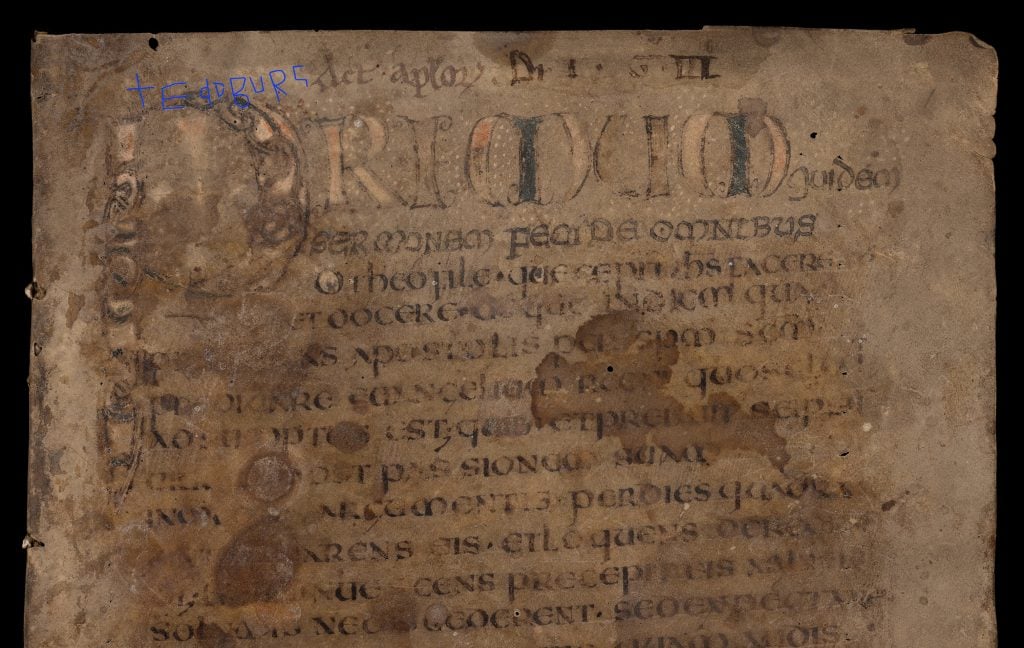

Academics have long speculated that the MS Selden Supra 30, a Latin version of the New Testament’s Acts of the Apostles, was used by women. A first clue was the addition of a prayer by a scribe different from the main text in which an anonymous woman makes a petition to God. Further evidence stemmed from palaeographer Elias Avery Lowe’s discovery in 1935 that the letters EADB had been incised at the bottom of page 47. Cutting-edge technology has turned the possible probable.

The technique, photometric stereo, converts 2D images into a 3D landscape and is capable of revealing markings one fifth the width of a human hair. It’s the first time such a method has been used to scan the annotations of a manuscript.

“The machine used to make the recording is called the Selene and it’s a prototype, the first of its kind,” John Barrett, senior photographer at the Bodleian Libraries, said. “I have spent the last 10 months making 3D recordings and this discovery has been exciting to behold for all involved.”

Annotated recording of the drypoint addition in the lower margin. Photo: courtesy University of Leicester

The practice of medieval readers marking books with their name isn’t uncommon. Usually, however, it was done in ink rather than with drypoint. The placement of the hidden writings throughout the volume, which is about the size of an A5 booklet, may be an attempt to state ownership or reverence for the work without detracting from the words of God. Just as alluring and mysterious are the series of sketches of human figures scattered throughout.

Hodgkinson’s next steps will be to further analyze the inscriptions and drypoint drawings in the contexts that they appear. “I hope that this work will shed further light on their meanings and significance, as well as perhaps providing clues about who added them to the manuscript and why.”

The research project was funded by the Helen Hamlyn Trust.