Art History

Pablo Picasso’s ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’ Revolutionized Modern Art. Here Are 3 Things You Should Know About It

The challenging composition paved the way for Cubism—and courted controversy.

The challenging composition paved the way for Cubism—and courted controversy.

Katie White

Pablo Picasso, it is said, worked until the day he died at the age of 91 on April 8, 1973. This weekend marks the 50th year since the Spanish artist’s passing. Five decades on, we are still grappling with the life and legacy of Picasso, a man once called the “genius of the century.”

Born in Malaga, in 1881, the son of an artist, Picasso revolutionized Modern art and become perhaps the most influential painter of the 20th-century. His works, despite their modernity, were a cacophony of references: El Greco, Cézanne, Gaugin, Manet, Henri Rousseau, all got their due, as did the static faces of ancient Iberian sculpture, along with Oceanic and African tribal arts, which Picasso marveled over in the studios of his fellow artists and in the museums of Paris. He’s probably most famous for co-founding the Cubist movement along with Georges Braque—but his influence was wide-ranging, as he developed innovative approaches to sculpture, ceramics, and linocuts. He even made absinthe glasses.

The mystique and machismo of his personal life are inexorably linked to this unapologetic artistic legacy. From his oeuvre, his famed Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) may best encapsulate his incendiary approach to art making.

The painting, which scandalized the public when it debuted in 1916, depicts five nude women in a room. These women, as one contemporary critic put it, have been “hacked up,” their sharp geometric features piled precariously together. A still life of fruit is placed incongruously before them, at the fore of the canvas.

The women’s features change as you move from left to right: the left-most figure stands with solemnity, seemingly plucked out of the Egyptian ancient world; the next two women seem inspired by ancient Iberian statues, and the two right-most women are the most startling of them all. These women wear mask-like faces, their bodies rendered with a fury of lines and shapes, which seem to reference African tribal masks. Picasso denied the influence of African art in the work, it was a conspicuously false declaration as Picasso is known to have visited the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro (known later as the Musée de l’Homme) in the spring of 1907 and seen a display of African art.

In fact, he’d begun his first sketches for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in October 1906 the same day he’d seen a Congolese Teke sculpture in the studio of Henri Matisse. These sketches would be the first of hundreds that would lead to its final form the next year in 1907. The painting, which Picasso had named Le Bordel d’Avignon, would not be shown publicly for almost a decade, seen first in Salon d’Antin in July 1916, in an exhibition organized by the poet André Salmon.

At this exhibition, Salmon renamed the canvas, which he had been calling Le bordel philosophique, to the more demure Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. The new name did nothing to quell the controversy it sparked, and the painting set Picasso on a path toward Cubism. On this anniversary week, we’ve taken a closer look at the famed work and found three facts that might make you see it in a new way.

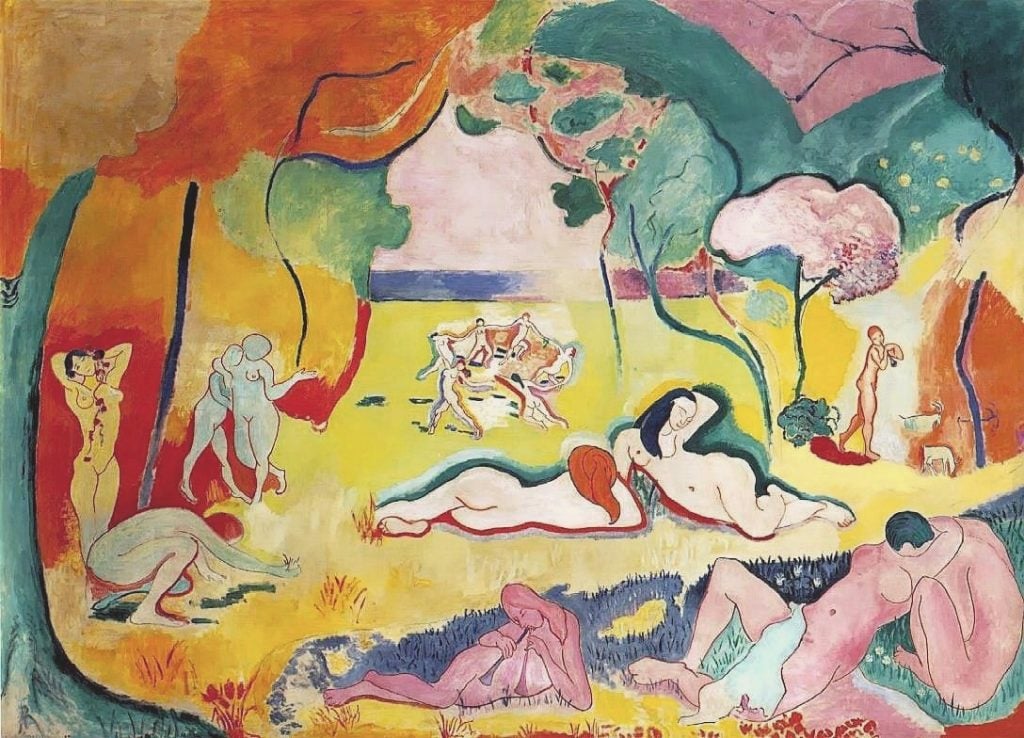

Henri Matisse, Joy of Life (Bonheur de Vivre) (1905–6). Collection of the Barnes Foundation.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon marked both a pivotal moment in the development of Modern art and a moment of schism between Picasso and his friend and artistic rival, Henri Matisse. Before the cataclysmic arrival of Les Demoiselles, Matisse had been the public figurehead of the burgeoning Modern art movement—and one who made the headlines, often against his own wishes. Matisse’s first brush with notoriety came in 1905 with the Salon d’Automne when he debuted his now acclaimed painting Woman with a Hat (1905) with its riotous and unreal colors. The exhibition would earn Matisse and his followers the name Les Fauves—a designation critically bestowed by art writer Louis Vauxcelles who described the Salon’s juxtaposition of these experimental works alongside classicizing sculpture as “Donatello chez les fauves” (Donatello among the wild beasts). This air of controversy clung to Matisse, heightening in 1906 and 1907 with the unveiling of his scandalous painting Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra) (1907) (when this painting was shown at the Armory Show of 1913 in New York City, it sparked public outrage).

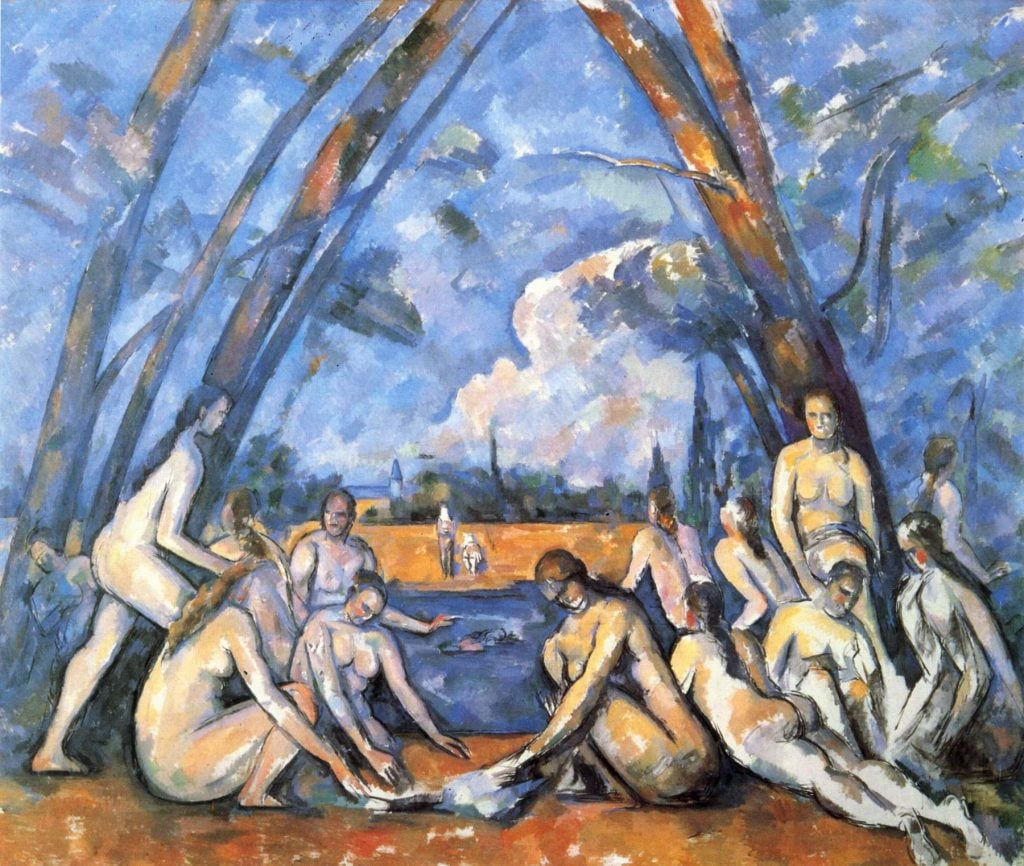

Meanwhile Picasso, who had passed popularly but uncontroversially through his Rose and Blue periods, was still seeking to define his vision—one that would catapult him to the fore of the Modern art movement. Les Demoiselles would do just that, with such startling force that Matisse seemed timid in comparison. Les Demoiselles, in fact, has sometimes been interpreted as Picasso’s retort to Matisse’s 1905 canvas Bonheur de Vivre, which, like Picasso’s canvas, took inspiration from Paul Cézanne’s The Large Bathers—a painting that only posthumously come to public attention through a show organized by dealer Ambroise Vollard. Struck by Cézanne’s nearly faceless women, Picasso took his canvas in a starkly more confrontational direction than Matisse’s pleasurable idyll.

Paul Cézanne, The Large Bathers (1898). Collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

“With the bizarre painting that appalled and electrified the cognoscenti, which understood the Les Demoiselles was at once a response to Matisse’s Le bonheur de vivre (1905–1906) and an assault upon the tradition from which it derived, Picasso effectively appropriated the role of avant-garde wild beast—a role that, as far as public opinion was concerned, he was never to relinquish,” art critic Hilton Kramer wrote in an essay, continuing, “…there was no question as to which was the more shocking or more intended to be shocking. Picasso had unleashed a vein of feeling that was to have immense consequences for the art and culture of the modern era while Matisse’s ambition came to seem, as he said in his Notes of a Painter, more limited—limited that is, to the realm of aesthetic pleasure.”

Edouard Manet, Olympia (1863). Collection of Musee D’Orsay.

Picasso never adopted the poet André Salmon’s edulcorating titling, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, calling it instead mon bordel (my brothel), or Le Bordel d’Avignon, for the rest of his life. Importantly, the Avignon of the title refers not the French city, but to a Barcelona street notoriously home to the city’s brothels—where Picasso was known to be a client. While depictions of prostitutes and courtesans are age old, artistic convention situated such compositions in exotic locales or in a classical or mythical pasts that offered a comforting degree of distance to the viewer.

In 1863, Edouard Manet first fractured the illusion of distance with Olympia (1863), a canvas that frankly pictures a contemporary woman, naked, with a courtesan’s black ribbon around her neck. She rests upon a crumpled bed, her shoes dirtied, a servant beside her, staring boldly outward. The proto-Cubist Les Demoiselles goes one step further, shattering the women’s figures and, in turn, shattering the distance between the viewer and the painted world. “A brothel may not in itself be shocking. But women painted without charm or sadness, without irony or social comment, women painted like the palings of a stockade through eyes that look out as if at death—that is shocking,” art historian John Berger wrote of the image.

Many historians and critics characterize Les Desmoiselles as an impulsive, even sacred exorcizing of artistic demons by Picasso, borne of a singular impassioned moment. But in his essay “The Philosophical Brothel,” art historian Leo Steinberg details just how arduously Picasso constructed the composition, creating hundreds of sketches in a period of months, slowly shapeshifting it toward its final form. Ultimately, Picasso choose to place the viewer within the bordello itself; in fact, some have convincingly suggested that Picasso’s insistence on calling the painting a “bordello” was his oblique allusion to the French world “bordel,” meaning “mess,” and the very messiness that goes into the constructing a work of art.

Through these sketches, one can witness an important transformation. Picasso had originally included two male figures in the composition—a sailor and a medical student, expected customers, as one sketch clearly shows. He then pivoted the composition, turning the scene so that the men stand ostensibly on our side of the canvas.

“Overnight, the contrived coherences of representational art—the feigned unities of time and place, the stylistic consistencies were all were declared to be fictional,” Steinberg writes. “The Demoiselles confessed itself a picture conceived in duration and delivered in spasms. In this one work Picasso discovered that the demands of discontinuity could be met on multiple levels: by cleaving depicted flesh; by elision of limbs and abbreviation; by slashing the web of connecting space; by abrupt changes of vantage; and by a sudden stylistic shift at the climax. Finally, the insistent staccato of the presentation was found to intensify the picture’s address and symbolic charge: the beholder, instead of observing a roomfuI of lazing whores, is targeted from all sides.” We can see Les Demoiselles, but they too can see us.

Detail of the still life in Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

We might ask ourselves about the peculiar still life that hovers at the lower edge of the painting. On a white tablecloth, Picasso has placed an apple, a pear, a bunch of blue-gray grapes, and a slice of pink melon. Scholars’ interpretations of this arrangement of fruit have varied but all suggest a function that underscores the fraught sexuality of the scene.

For Steinberg, the still life bridges the space within the canvas with the viewer’s world beyond. “The picture impales itself on a sharp point. It is speared below by a docked tablecloth, an acute corner over laid by a fruit cluster on a white table. The table links two discontinuous systems; space this side of the picture couples with the depicted space,” Steinberg writes. This fruit has been offered for our consumption, much like the bodies of the women themselves.

“Anybody can see that the ladies are having company. We are implied as the visiting clientele seated within arm’s reach of the fruit—accommodated and reacted to. It’s like a difference between eavesdropping on a group too busy to notice or walking in like the man they’ve been waiting for. Our presence rounds out the party, and the tipped tabletop plays fulcrum to a seesaw: the picture rises before us, because we have to hold our end down,” he explains.

While Steinberg see the fruit echoing “the harsh junctures of human anatomies,” other scholars see the still life as more explicitly and intrinsically sexual. In the essay “The Neglected Fruit Cluster in Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon“, historian L.D. Steefel suggests that the still life is really “a clustered phallic ensemble in essentially static repose.” In this interpretation, the still life draws forth the male sexual presence in the decidedly female space. For Steefel, who sees the painting as alive with orgiastic energy, this cluster of fruit may hint at female sexual power and even violence. “It could be seen as a proprietary metamorphosis of the dismemberment into a fruitful element,” he suggests. “Best of all it could speak to the hallucinatory mood of the whole image as a dangerous metaphor for male mutilation by Amazonian females.”