Art & Exhibitions

How Pacific Standard Time Is Writing Long-Overlooked Chicano Artists Back Into Art History

The learning curve for museums was steep.

The learning curve for museums was steep.

Catherine Wagley

On a Monday morning in May 2015, artist David Avalos stood on the stage of a packed auditorium at the Getty Center in Los Angeles. He described a day in 1977 when white supremacist and former KKK leader David Duke announced that he would patrol the San Diego-Mexico border. Duke attached a hand-drawn sign to his car door that read “Klan Border Watch.”

Avalos, a San Diego native known for his role in the Chicano Mural Movement, and his friend, fellow artist Yolanda López, protested Duke’s effort. López made a poster, which Avalos pulled up on the screen. It showed a fierce figure in an Aztec headdress crumpling an “immigration plans” flier and saying, “Who’s the illegal alien now, pilgrim?”

“Since its first appearance, there has never been a year in which that poster was not relevant,” Avalos said to the crowd. It was the second day of “LA/LA: Place and Practice,” a symposium that would change the course of the Getty-funded initiative PST: LA/LA, which officially kicks off this week.

The sprawling initiative, which includes 88 affiliated exhibitions across Southern California, comes five years after PST: Los Angeles 1980–1945, a 60-institution, $10 million effort that frequently felt boosterish, offering LA arts venues the opportunity to rediscover and celebrate their own histories. When the Getty announced that the next version would focus on LA and Latin America, it was clear that this self-congratulation would not recur. Despite the large Latinx population in Southern California, major local institutions have too rarely exhibited the work of Chicano and Latino artists.

This marginalization led to some skepticism from local artists early on in the PST planning process. How could an effort helmed by the very institutions that had historically excluded them truly capture the contributions of local artists of Latin American descent? The learning curve would be steep.

“The initial launch of LA/LA did not seem to have any mention of the local community,” says artist Ken Gonzales-Day, whose work appears in four PST shows and who organized “Place and Practice” with curators Bill Kelley, Jr. and Pilar Tompkins Rivas. “As you know, this is a horrible time to be of Mexican descent in the US. If these shows could help in any way, that would be potentially great.”

Over a series of dinners with local artists and arts organizers, they discussed what they, as Latinos in LA, wanted from PST. “We talked about how there had historically been a complete lack of interest by institutions,” says Kelley, Jr. “We asked, ‘What should we do? What should we expect?’”

After an October 2014 symposium at the Getty at which art historians and curators predominately from Latin America shared their PST progress, Kelley, Tompkins Rivas, Gonzales-Day, and others decided to write a letter. They worried that, in the context of PST, Latin American scholarship still overshadowed the emphasis on the artists in museums’ own backyards. “We came up with an obnoxious name for ourselves, something like Artists and Curators and Latino Cultural Activists of LA,” Kelley says.

Joan Weinstein, the deputy director of the Getty Foundation, invited them to come to the museum to talk. “We said, ‘Come to us,’” Kelley recalls. So they met at Self-Help Graphics & Art, a 30-year-old alternative space in the East LA neighborhood of Boyle Heights. The “Place and Practice” conference emerged out of that meeting.

“I had actually forgotten about the letter,” Weinstein says now. “The way it works is that we put out a call. We don’t tell museums what to do. The programming comes from the community.”

But the symposium and other conversations about the representation of Chicano artists clearly had an effect. Nine of the initial research proposals the Getty received in 2014 addressed Chicano artists. The final roster of shows includes 16 such shows, plus several thematic exhibitions that bring together the work of Latin American and Chicano and Latino artists.

Pedro Arias’s La Marcha de la Reconquista Sacramento bound (c. 1971). Courtesy of the photographer and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center © Pedro Arias.

The conference also had among the largest attendance of any Getty-hosted symposium. “That was a room full of brown people,” Kelley notes, “which just goes to show you: The problem isn’t attendance.”

Lowery Stokes Sims, the co-curator of the Craft and Folk Art Museum’s “The US-Mexico Border: Place, Imagination, Possibility,” which presents contemporary art about the border, says the event helped her and collaborator “find a bridge between the work of Chicano artists in the 1970s and ‘80s and contemporary practitioners.” Their show includes work by Judy Baca, a longtime LA icon, as well as that of younger artists like Julio César Morales, whose Undocumented Interventions watercolors document desperate border crossing strategies, such as families hiding a child in a piñata or a cushion.

Notably, some curators who have long specialized in Chicano art have chosen to go the opposite direction for PST, casting a wider net to highlight themes explored by both local and Latin American artists.

Chon Noriega, the director of UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center (CSRC), consulted with directors and communication staff at the Getty, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), and other institutions in the lead-up to the first PST and the second. He and the CSRC also helped research and produce the catalogue for a show of Chicano photographer Laura Aguilar’s work at the Vincent Price Museum, as well as an Autry Museum exhibition about La Raza, a magazine founded in 1967 in LA’s Chicano community. But for the exhibition he curated himself, Noriega took a more open-ended approach.

Carmen Argote’s 720 Sq. Ft.: Household Mutations (2010). © Carmen Argote, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

“Home—So Different, So Appealing,” which opened at the LACMA in May, includes works by 42 Latino and Latin American artists that grapple with the idea of home and belonging. The show, organized in collaboration with Pilar Tompkins Rivas and Mari Carmen Ramírez of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, spans borders and time periods: Footage from 1974 of the late Chilean-American artist Gordon Matta Clark dissembling a house plays on a monitor next to beige carpeting that the LA-based, Mexican-American artist Carmen Argote took from her childhood home and draped from the ceiling onto gallery floor.

“‘Home’ was our attempt to move beyond the constricting framework for ‘ethnic art’ exhibitions—basically, you set up some premises about ethnic culture and its art, then select artworks that illustrate those premises,” Noriega says. “I’m not discounting the idea of a ‘Chicano art,’ since it is as valid as any art category defined by identity, such as American art. It just seemed to me that in the current institutional environment, ethnic art exhibitions also became complicit in reaffirming the exclusion that made them necessary.”

The Getty also sought to foster the kind of ambitious, border-crossing exhibition that Noriega wanted to create. In addition to the symposium focused on Chicano art, the institution hosted a series of other conferences to help institutions prepare for PST, including one about how to effectively arrange loans from Latin American museums. “Some institutions have never done that,” Weinstein says. “I think that will be one of the great accomplishments of Pacific Standard Time, that Latin American and Latino art can be in dialogue with one another.”

Judithe Hernández’s The Purification (2013). © Judithe Hernández, courtesy Millard Sheets Art Center.

To predict how much—or how little—these exhibitions might affect the lives and careers of Latino and Chicano artists, consider how the first PST affected Patssi Valdez, a member of the 1970s activist performance group ASCO, which was the focus of one of the initiative’s most widely acclaimed exhibitions of Chicano art. (All told, five exhibitions in 2011’s PST focused on the field.)

The show prompted other institutions to take an interest in ASCO—but often, they weren’t as enthusiastic about showing her more recent material. Valdez now primarily works as a painter, making bold, surreally figurative domestic scenes. “I find it very interesting [that people are always interested in ASCO], which is great and fine,” she says. “But I’m hoping someday that my paintings, too, will receive critical attention.”

Now, Valdez’s new work hangs alongside the old in a two-person PST show at the Millard Sheets Art Center, “Judithe Hernández and Patssi Valdez: One Path Two Journeys.” Hernández, another sole female member of a Chicano artist collective (Los Four), invited Valdez to participate in the show. Although they knew each other back in the late 1960s and ‘70s, their friendship is newer, formed as both women learned to navigate the current LA landscape.

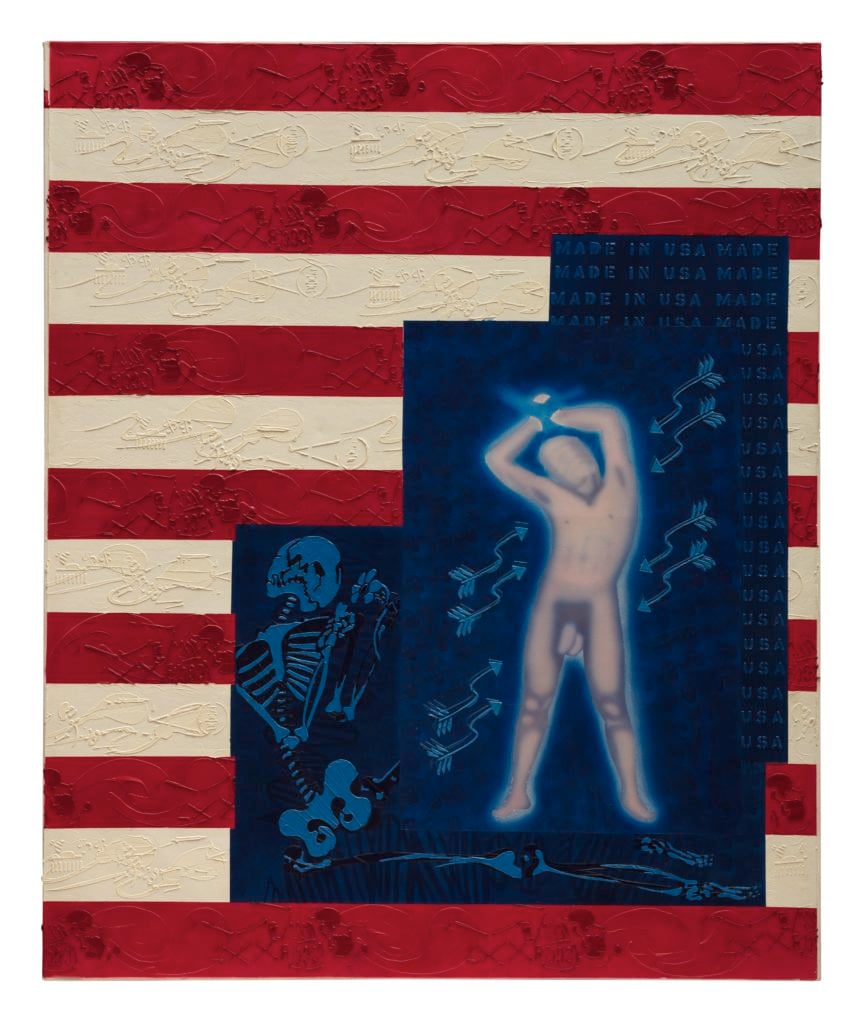

Gerardo Velázquez, The Neglected Martyr (1990). Photo by Fredrik Nilsen.

One of the lasting legacies of this edition of PST is likely to be the realization of just how much scholarship remains to be done on Latino and Chicano artists. But the initiative has allowed some institutions to make a promising start.

One of PST’s more ambitious shows, “Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano LA,” a two-venue exhibition at MOCA’s Pacific Design Center outpost and the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, explores 30 years of work by queer Chicano artists and their collaborators. “We’ve been spending a lot of time in different storage facilities,” says the show’s co-curator C. Ondine Chavoya.

During the research phase, the ONE Archive significantly expanded its holdings related to Chicano art, which stands to benefit future scholars of the material. (Artist-musician Gerardo Velazquez’s bandmates from Nervous Gender, the punk band he co-founded, donated his papers ahead of the opening, for instance.)

But the process also revealed that institutions and audiences have a lot more to learn. “As we would talk about it, there was always this presumption that it would be a small show,” Chavoya observes. “People would ask, ‘Is Felix Gonzalez Torres in your show?’” (Torres being queer, Latino, and famous.)

He is, in fact, not included. But 47 other artists are.