People

Painter Brice Marden, Whose Loping Lines and Brash Abstractions Defied the Artistic Trends of His Time, Has Died at 84

His daughter announced the news on Instagram, saying, "Dad died peacefully last night at home."

His daughter announced the news on Instagram, saying, "Dad died peacefully last night at home."

Sarah Cascone

Artist Brice Marden, whose abstract paintings defied easy categorization, died at home on Wednesday in Tivoli, New York. The 84-year-old artist’s daughter, Mirabelle Marden, announced the news on Instagram.

Marden was diagnosed with cancer in 2017, the same year he joined Gagosian gallery.

“Brice Marden was one of our greatest American artists, whose achievement in continuing and extending the tradition of painting has long been recognized and celebrated the world over. He was a painter of rare insight into the pleasure and poetry of his medium; always dedicated to gesture, chance, substance—the elemental matters of art,” Larry Gagosian said in an email to Artnet News. “It has been an honor to share his masterful work with an international audience. This loss is profound, and he will be missed.”

Despite his extended illness, Marden maintained his practice up until the end, painting in his studio as recently as this past weekend, according to his daughter, who wrote on Instagram that “he was lucky to live a long life doing what he loved.”

Brice Marden prior to his death. Photo courtesy of Gagosian.

“I have been able to work through it all. It hasn’t made me hurry things up. It hasn’t made me work any differently. It’s just been an extra thing to think about,” Marden said of his illness in a 2019 interview with the New York Times.

Gagosian had staged a one-night-only sold-out exhibition of Marden’s work the previous summer at Villa Malaparte, the famed Italian Modernist home on the Italian island of Capri, attended by the likes of NBA star Lebron James, record producer Jimmy Iovine, and mega collector Steve Cohen.

Later that fall, on the occasion of his 80th birthday, Marden unveiled his largest-ever commission, a five-panel painting titled Moss Sutra With the Seasons (2010–15), created for husband-and-wife collectors Mitchell Rales and Emily Wei Rales’s private museum, Glenstone, in Potomac, Maryland.

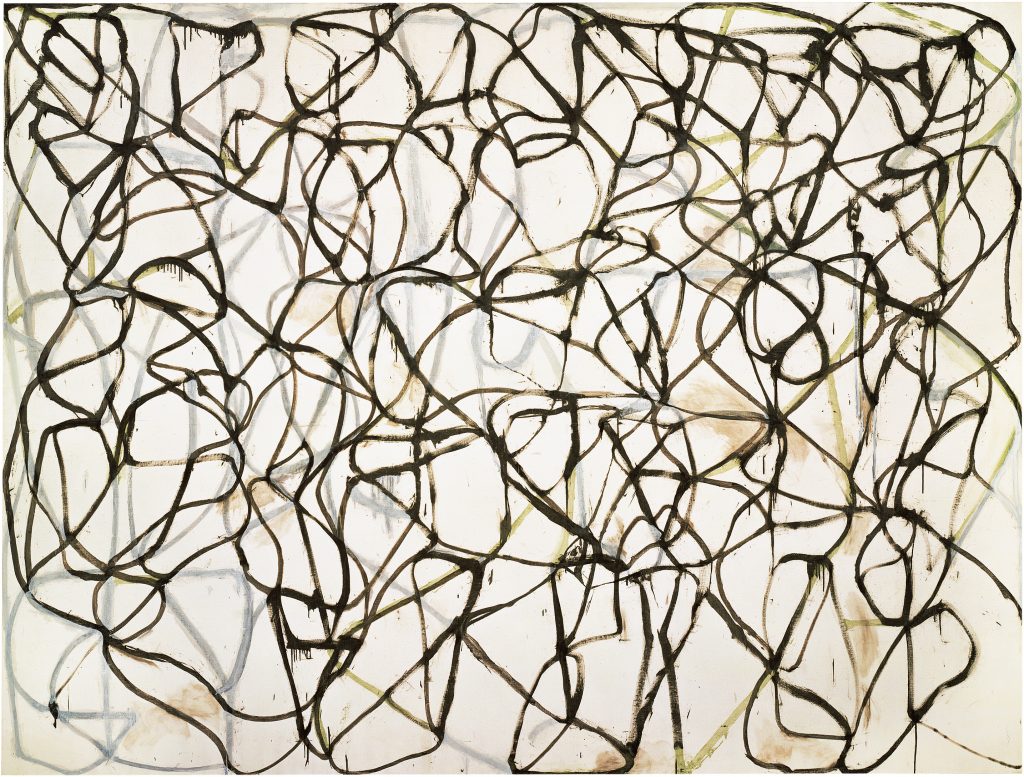

Brice Marden, Moss Sutra With the Seasons (2010–15). Collection of Mitchell Rales and Emily Wei Rales, Glenstone, Potomac, Maryland. Photo by Ron Amstutz.

The artist’s auction record currently stands at $30.9 million, set at Christie’s New York in 2020, according to the Artnet Price Database. He has six results surpassing the $10 million mark, all in the last decade—four of which came after signing with Gagosian.

Marden’s 60-year career began in 1963, when he graduated with an MFA from the Yale School of Art. Coming of age at a time when Abstract Expressionism was giving way to Pop art and Minimalism, Marden has been loosely grouped with the latter, but didn’t fit neatly into any one movement.

“I felt much more in tune with Abstract Expressionism,” Marden told Bomb magazine in 1988. “The actual act of painting, the physicality of the thing, became the substance of Abstract Expressionism.”

Brice Marden with an early work. Photo courtesy of Gagosian.

After finishing school, the Westchester native moved to New York and became a security guard at the Jewish Museum. Standing watch over the institution’s 1964 Jasper Johns retrospective was an influential moment for the young Marden, who had his first solo show two years later at Manhattan’s Bykert Gallery.

With painting decidedly out of vogue, reviews for this inaugural outing, featuring thickly painted surfaces blended with turpentine and beeswax, were mixed. Undeterred, Marden, by now working as a studio assistant for Robert Rauschenberg, slowly made a name for himself with large, often monochromatic canvases featuring flat, rectangular panes of color.

“People were saying ‘painting is dead,'” Marden told Christie’s in 2020. “It was my way of saying what can be done.”

Brice Marden, Cold Mountain 6 (Bridge), 1989–91. Collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, ©Brice Marden/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Marden married fellow painter Helen Marden, née Helen Harrington, who he met while she was waitressing at famed New York art bar Max’s Kansas City, in 1968. The two went on to have two daughters, Mirabelle (who from 2001 to 2009 co-owned the Lower East Side gallery Rivington Arms) and Melia. He also has a son, Nicholas, from his first marriage to Pauline Baez, sister of singer Joan Baez.

As professional success came, Marden was selected to show at Documenta 5 in Kassel in 1972, and had a retrospective at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1975. Later accolades would include showing at the 1997 Venice Biennale. Prior to joining Gagosian, Marden spent over two decades represented by New York dealer Matthew Marks.

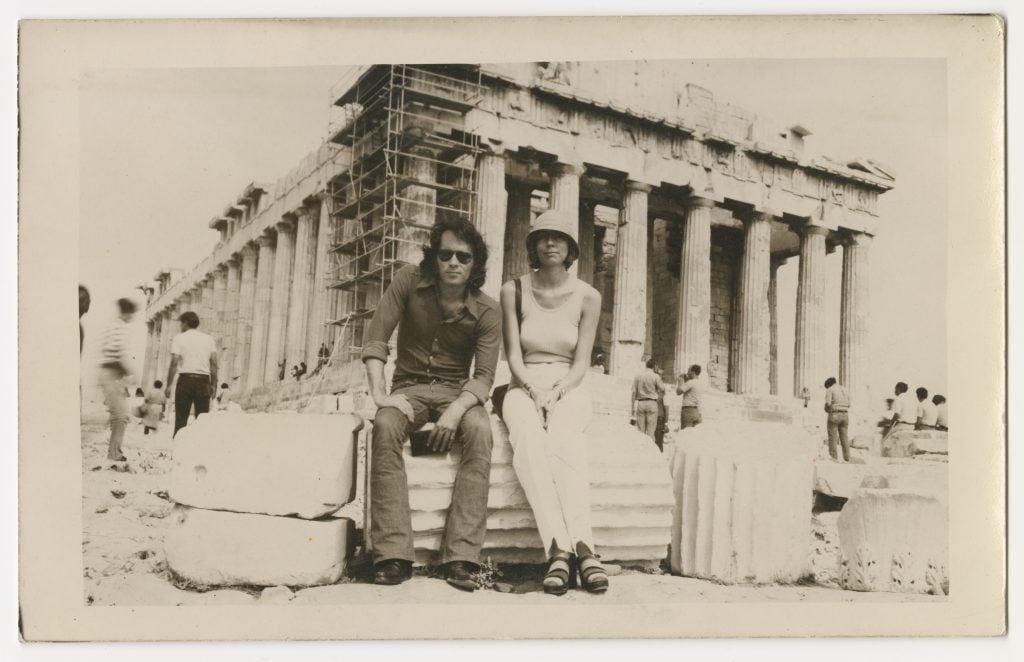

Over the years, travel was an important point of departure for Marden’s career, including trips to Italy, France, Thailand, Sri Lanka, and India. After a 1971 trip to Hydra, Marden and his wife bought a home and studio there, returning annually to the Greek island. They eventually owned six properties scattered across the globe, including one in Marrakech and a hotel on the Caribbean island of Nevis.

A visit to China in 1984 inspired Marden to begin introducing gestural, calligraphic-inspired markings into his canvases and drawings, sometimes painting with tree branches dipped in ink. His well-known “Cold Mountain” series was named after the poetry of Tang dynasty hermit Han Shan.

Brice and Helen Marden at the Parthenon in Athens. Photo courtesy of Gagosian.

Creating these later, layered canvases and their swirling, undulating lines was a both an additive and subtractive process, with Marden often building up and scraping away the paint until satisfied with the composition—a decision that he once told the Houston Chronicle was sometimes made for him when art handlers arrived to pick up works for an exhibition.

“When the painting really lives, has a right to exist on its own strengths and weaknesses, I consider it finished,” Marden said in the catalogue for a 2006 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. “When I have put all I can into it and it really breathes, I stop. There are times when a work has pulled ahead of me and goes on to become something new to me, something that I have never seen before; that is finishing in an exhilarating way.”