People

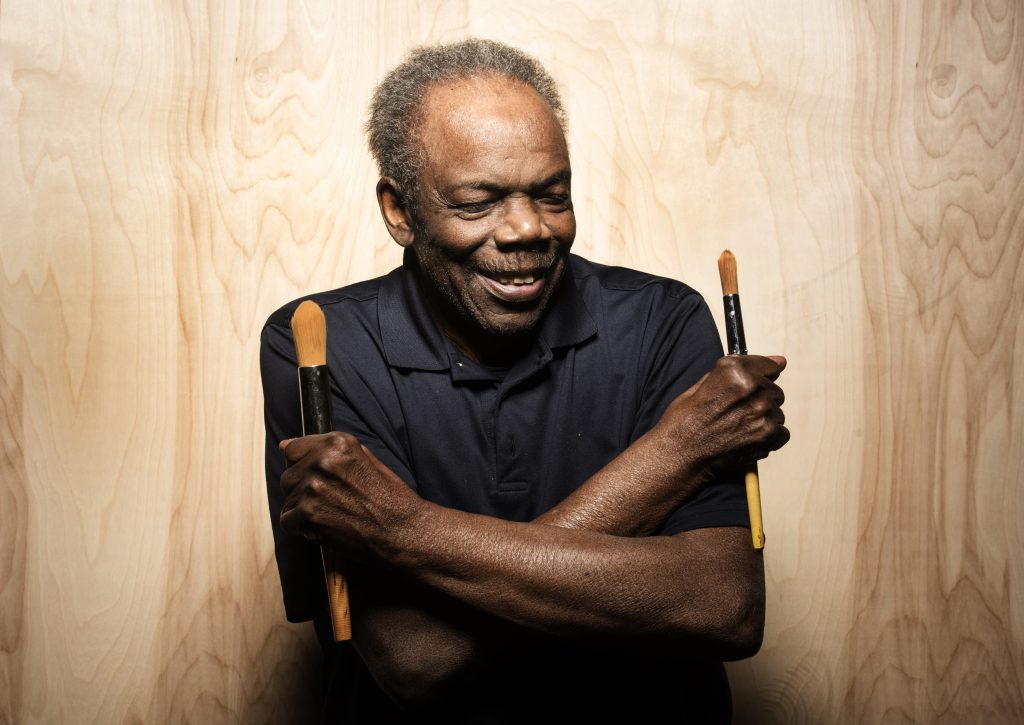

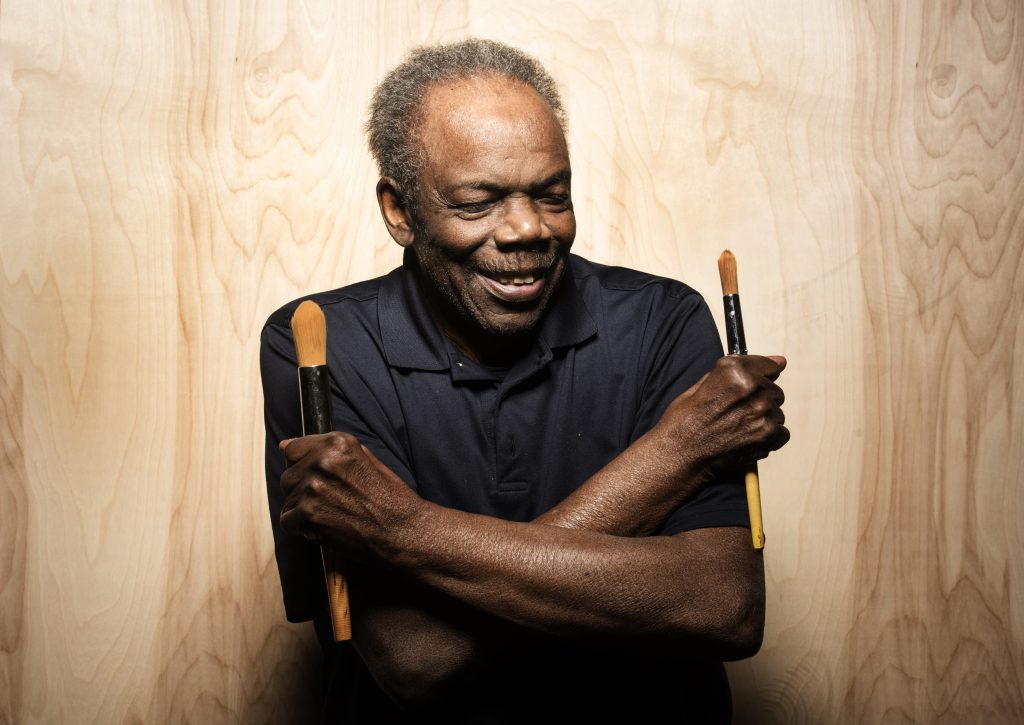

Painter Sam Gilliam, Celebrated for His Boldly Colored Draped Canvases, Has Died at 88

The abstract painter died at his home in Washington, D.C.

The abstract painter died at his home in Washington, D.C.

Helen Stoilas

The abstract painter Sam Gilliam, the first Black artist to represent the U.S. at the Venice Biennial in 1972, died at his home in Washington, D.C., on Saturday, June 25, age 88. The cause was kidney failure, according to his New York gallery, Pace and his Los Angeles gallery, David Kordansky Gallery.

“Throughout his seven-decade career, Gilliam reinvented and continuously reshaped abstract painting and sculpture,” Pace said in a statement. “Incorporating rich constellations of forms, textures, and materials to forge inventive compositions. His work has exerted a profound influence on subsequent generations of artists.”

Born in Tupelo, Mississippi in 1933, to a railroad worker and homemaker, Gilliam moved with his family to Louisville, Kentucky soon after his birth. “Since my mother had eight children, it was necessary for her to be busy doing things,” he told the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art in a 1984 interview. “She kept me on cardboard and paper, drawing, so I wouldn’t get in the way. It was observed by her friends but it really kept me quiet. So Mom simply bought more paper.”

Installation view of Sam Gilliam, Spread (1973). Image: Ben Davis.

As a young man, he studied at the University of Louisville, where he got his B.A. in 1955—in its second-ever desegregated class of students—and, after a two-year stint in the U.S. Army, his M.F.A. in 1961. He soon after moved to Washington, D.C., and started teaching art in high schools. He worked on his own paintings on the weekends, applying acrylic paint on unprimed canvas, and then stretching it onto frames with distinct beveled edges.

Gilliam became associated with the Washington Color School, a movement of abstract artists working in the U.S. capital starting in the 1950s, although he was never an official member, forging his own distinct path. He instantly gained critical attention with a solo exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1969, where he draped massive swathes of painted canvas in the museum’s four-story atrium. The Washington Star art critic Benjamin Forgey described the show at the time as “one of those watermarks by which the Washington art community measures its evolution.”

In 1972, Gilliam was part of a group exhibition with the artists Ron Davis, Diane Arbus, Keith Sonnier, Jim Nutt, and Richard Estes, organized in the American Pavilion of the Venice Biennale by the legendary curator Walter Hopps. He returned to Venice in 2017, where his monumental canvas Yves Klein Blue was draped across the entrance of the Giardini’s central pavilion.

Sam Gilliam’s work Yves Klein Blue at the Venice Biennale in 2017. Photo: Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery.

“I first encountered Yves Klein while stationed with the army in Japan. There was a Klein exhibition in Tokyo,” Gilliam told Artforum. “The Gutai group was being born, and I was in the army, and I thought nothing about whether I would be an artist or not. In fact, I probably thought that I would never be an artist. But Klein had an effect on me, and I thought about making art beyond the interiors that it is usually presented in, about making art more in the outside world.”

In 1975, he created one of his largest draped canvas installations, Seahorses, for the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The six-part work covered the two exterior walls of the institution’s East Façade, and evolved from the artist’s idea, based on Greek mythology, that the large bronze rings that circled the building were like those used to tie seahorses to Neptune’s temple.

Although he came up during the Civil Rights Era, Gilliam’s work remained staunchly abstract, and he rarely addressed political or social themes, which sometimes caused friction in the wider arts community. “I remember when [Black activist] Stokely Carmichael called a group of us together to tell us of our mission,” he told the Washington Post in a 1993 interview. “He said: ‘You’re Black artists! I need you! But you won’t be able to make your pretty pictures anymore.’”

But despite Gilliam’s revolutionary contributions to abstract art, his work did not receive the recognition it deserved in the art market or the upper levels of the institutional field until later on in his life. In 2019, Gilliam’s installation Double Merge (1968) was installed in the Dia Beacon art center in upstate New York, where it remains on long-term display until August 7. It was jointly acquired last year by Dia and the Museum of Fine Art Houston , where it is due to travel this year.

Installation view of Sam Gilliam’s Double Merge (1968) at Dia: Beacon. © Sam Gilliam/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York. Courtesy of Dia Art Foundation.

“Sam Gilliam was truly one of the most important artists of the last century,” says Jessica Morgan, the director of the Dia Art Foundation. “His masterful explorations of color, materials, and space redefined the possibilities of painting as a medium, allowing the work to move from the wall and become three dimensional. His monumental canvas installation Double Merge at Dia Beacon demonstrates his radical site-responsive approach—suspended from the ceiling, Gilliam’s ‘Drape’ paintings can never be seen the same way twice. His work has had incalculable influence and impact throughout the art world. He will be deeply missed.”

The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., is also currently hosting a major survey of the artist’s work, “Sam Gilliam: Full Circle,” through September 11. The museum’s head curator, Evelyn Hankins, who organized the show, said having the opportunity “to spend time with Sam in his studio, not three miles from the Hirshhorn, and to share the significance and magic, even, of his art with museum visitors will always be a foundation of my work in Washington. His passing marks a huge loss for the DC arts community and the broader arc of contemporary abstraction.” The Hirshhorn’s director Melissa Chiu added that “among the lessons of his six-decade visual practice is the degree of courage that is required to transform the history of art.”

Gilliam is survived by his wife, Washington, D.C. art dealer Annie Gawlak; his three daughters, Stephanie Gilliam, Melissa Gilliam and Leah Franklin Gilliam, from his first marriage to Dorothy Butler Gilliam—the first African American woman reporter at The Washington Post; three sisters; and three grandchildren.

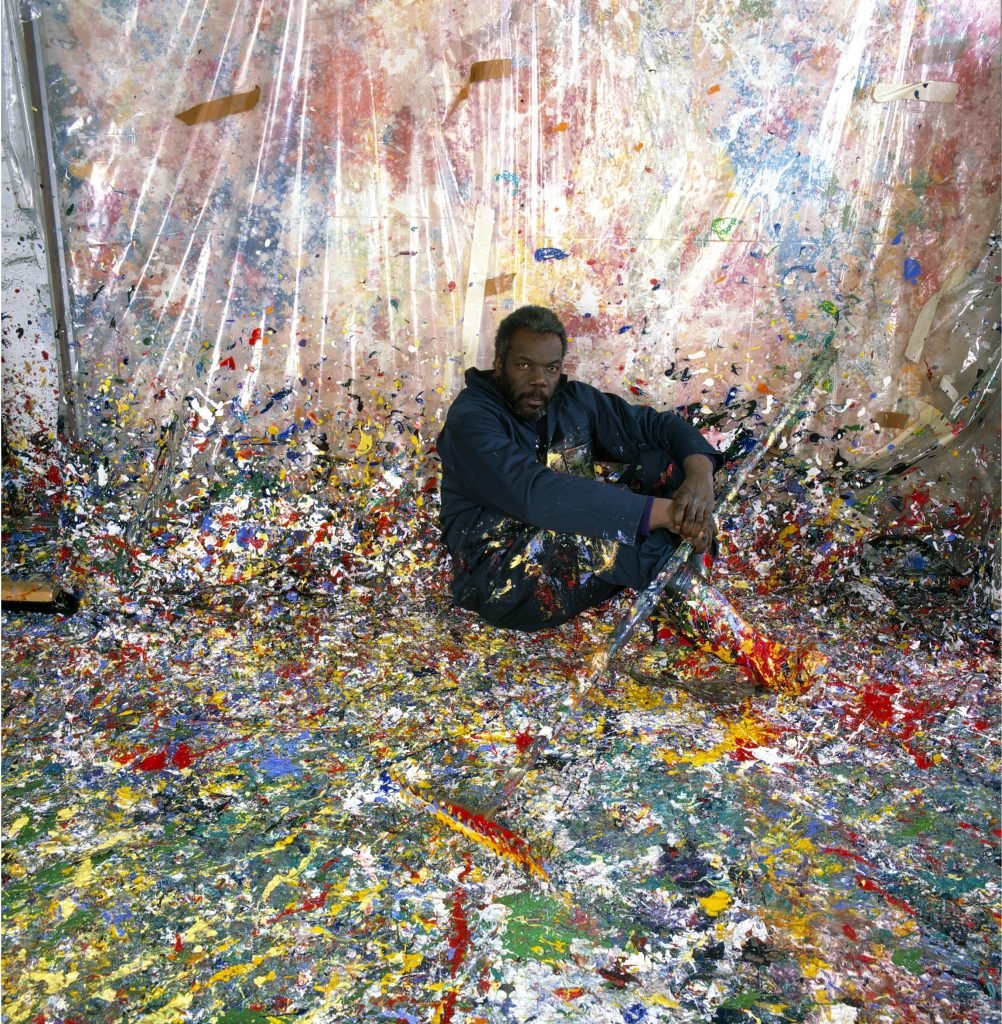

Portrait of African American painter Sam Gilliam, seated on the floor of his paint splattered studio, Washington, D.C., 1980. (Photo by Anthony Barboza/Getty Images)

“Sam changed the course of my life, like he inspired the lives of many others, as a generous teacher, mischievous friend, and sage mentor,” the Los Angeles dealer David Kordansky, who has represented Gilliam since 2012. “Above all, Sam embodied a vital spirit of freedom achieved with fearlessness, ferocity, sensitivity, and poetry.”

Jonathan Binstock, the curator a Gilliam’s first career retrospective at the Corcoran Art Gallery in 2005, told Artnet News: “In addition to developing and furthering this global conversation on abstract painting, he consistently sought new knowledge through his unique aesthetic research. He was never content to remain with a particular style or mode of working. He was always searching. And in the end, I think what he found, and what he demonstrated, is something so unique and incomparable, and something that is really a testament to a humanistic vision of the world.”

Binstock visited Gilliam in his studio in early April, and says he was “hard at work painting, innovating, and doing things he had never done before. He was thinking of new ways of working—ways that no one else has worked.”

“He would focus on, ‘What would happen if we did this?'” Binstock says of Gilliam’s development of these final works. “And after a while, he would begin to understand the new process that he was making. And the words would shift to: ‘Just you wait and see.'”