Art World

‘Paleoart,’ a New Book, Explores the Surprisingly Venerable Tradition of Depicting Dinosaurs

"Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past" delves deep into the history of an art form that imagines the lives of primitive beasts.

"Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past" delves deep into the history of an art form that imagines the lives of primitive beasts.

Caroline Goldstein

From National Geographic to Jurassic Park, the modern appetite for dinosaurs is insatiable. Our fascination with the monstrous creatures that roamed the planet comes from the very simple fact that no one has ever laid eyes on one before. As a result, more than an ounce of creativity and imagination is required to make sense of the prehistoric world they inhabited.

Artist Walton Ford has made a career out of imagining the oversize bodies of fantastical creatures, rendering naturalist illustrations in a style equally indebted to John James Audobon and Hieronymus Bosch.

Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past (2017). Image courtesy of TASCHEN.

It’s not surprising, then, that Ford is also a huge dinophile, as revealed in the new book Paleoart: Visions of a Prehistoric Past (TASCHEN, 2017). The book was conceived by Ford, and features a forward by him, as well as a book-length treatise by the writer Zoë Lescaze.

The illustrations within are co-selected by Ford and Lescaze, and amount to an illustrated history of “paleoart,” a contemporary term that describes modern illustrations of the prehistoric past, based on archaeological remains and other scientific details.

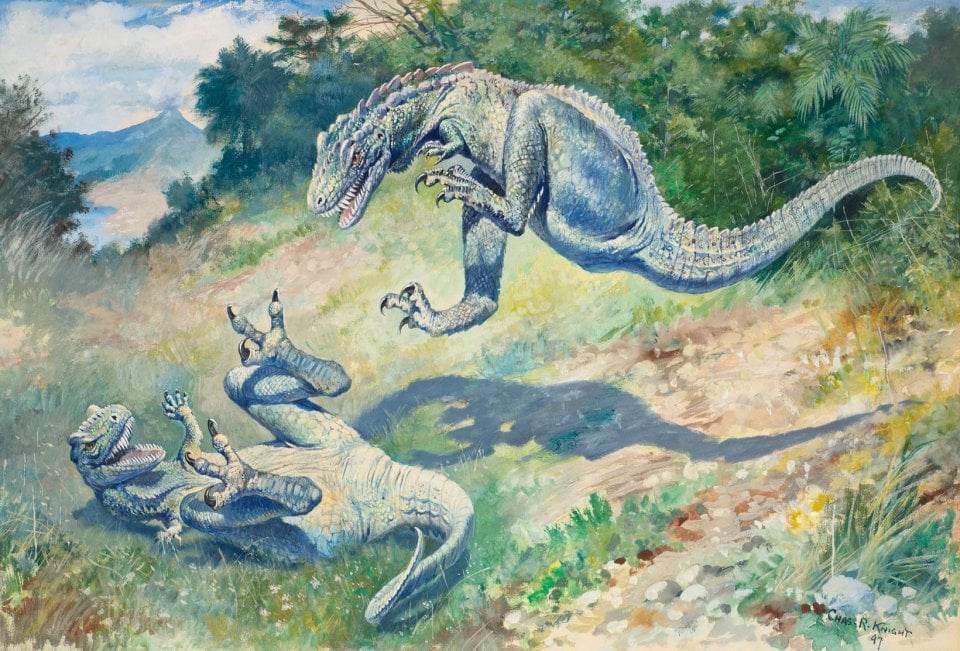

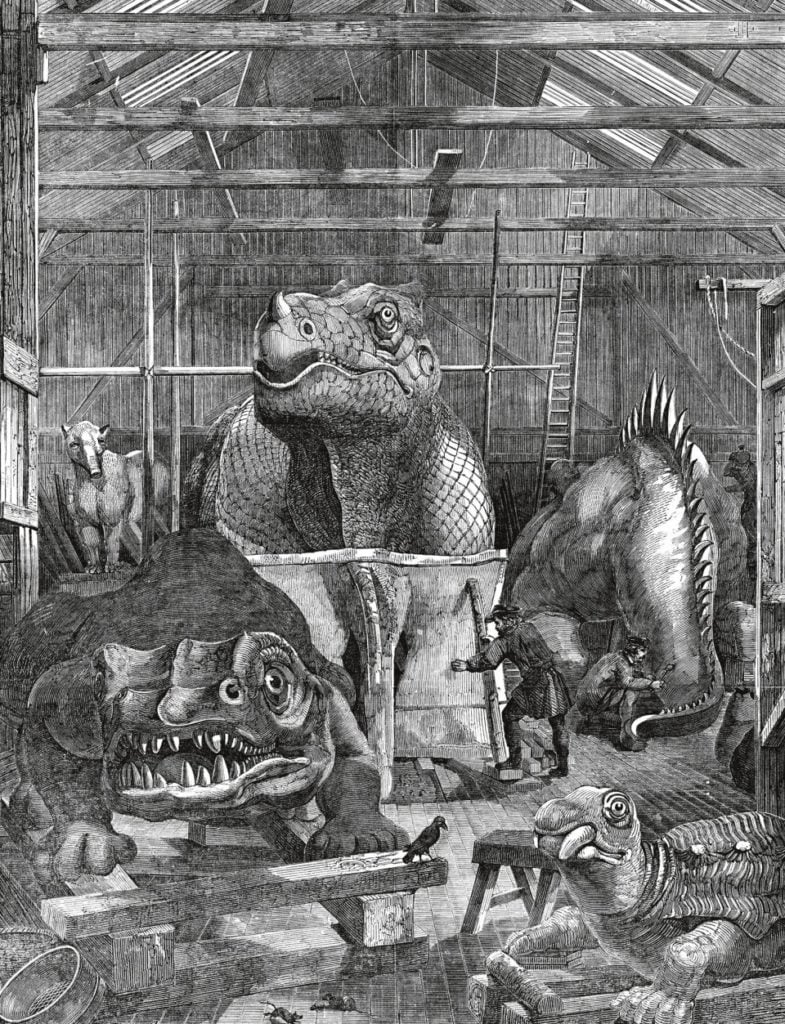

The practice dates back to the early 19th century, when scientists would use skeletal remains to approximate the physical characteristics of extinct creatures, often inserting biblical and mythological history into the scenes. The full spread illustrations and accompanying essay trace the art form from 1830 to 1990, depicting the mysterious realm of regal woolly mammoths, pterodactyls soaring over primordial landscapes, and overgrown lizards gouging one another.

See images of the prehistoric beasts below:

Charles R. Knight’s Laelaps (1897). © American Museum of Natural History, NY. Courtesy of TASCHEN.

Philip Henry Delamotte’s Model Room at the Crystal Palace (1853). © Courtesy of TASCHEN.

Heinrich Harder, reconstructed by Hans Jochen Ihle, Pteranodon (1982). Courtesy of TASCHEN.

Alexander Mikhailovich Belashov’s Tree of Life (1984). © Borrissiak Paleontological Institute RAS. Courtesy of TASCHEN.

Adolphe François Pannemaker’s The Primitive World (1857). © Courtesy of TASCHEN.

Alexei Petrovich Bystrow’s Inostrancevia, devouring a Pareiasaurus (1933). © Borrissiak Paleontological Institute RAS, courtesy of Taschen.