It is an absolute scene: gyrating bodies, sloshing glasses of white wine, people standing on the tables and chairs. One art dealer, with no shirt on, fingers towards the camera as the pounding hook of the 1980s hit Come on Eileen peaks. Too-ra-loo-ra Too-ra-loo-rye-ay! A large artwork edition by Ken Lum (sarcastically, it states “Pete Norris could use a drink!”) is in the background, probably shaking on its hook. Actually, all the walls of Berlin’s Paris Bar seem like they could be moving. The video, a 2015 clip an artist sent to me over text, cuts off.

The recently deceased Michel Würthle was almost certainly somewhere at that party, just out of the frame. The night was one momentary flicker in the legacy of the restaurateur, artist, collector, and co-founder of Paris Bar, who died last month. Some of those from the art world who haunt the restaurant feel sure they are not only dining there, but participating in Würthle’s cultural meta project.

You might not catch that drift right away: the street-side patio of Paris Bar, which glows under a red neon sign in the evening, and its cramped interior, are humming on a typical day, like any other hot spot. Plates of food are served by a lightly grumpy set of white-aproned servers. But a first hint that this place understands itself rather as a salon is a look at the diners: a healthy demographic of culture patrons, including artists, dealers, and collectors. They slice into nicely cooked but not overly memorable entrecôte steaks, and most of them have been doing this for nearly 50 years.

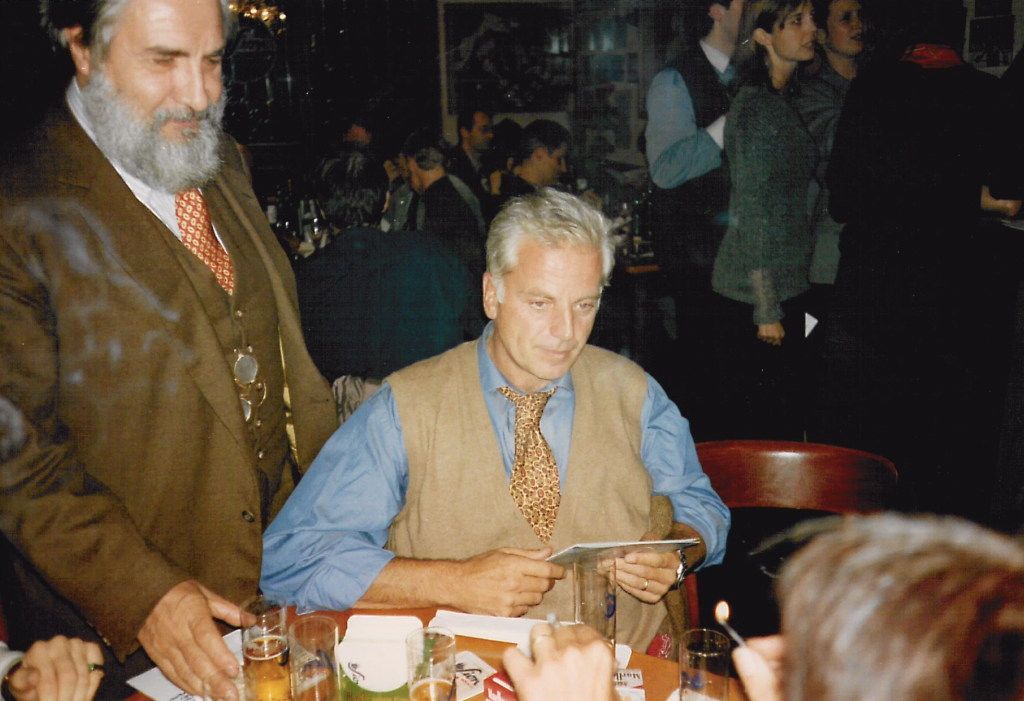

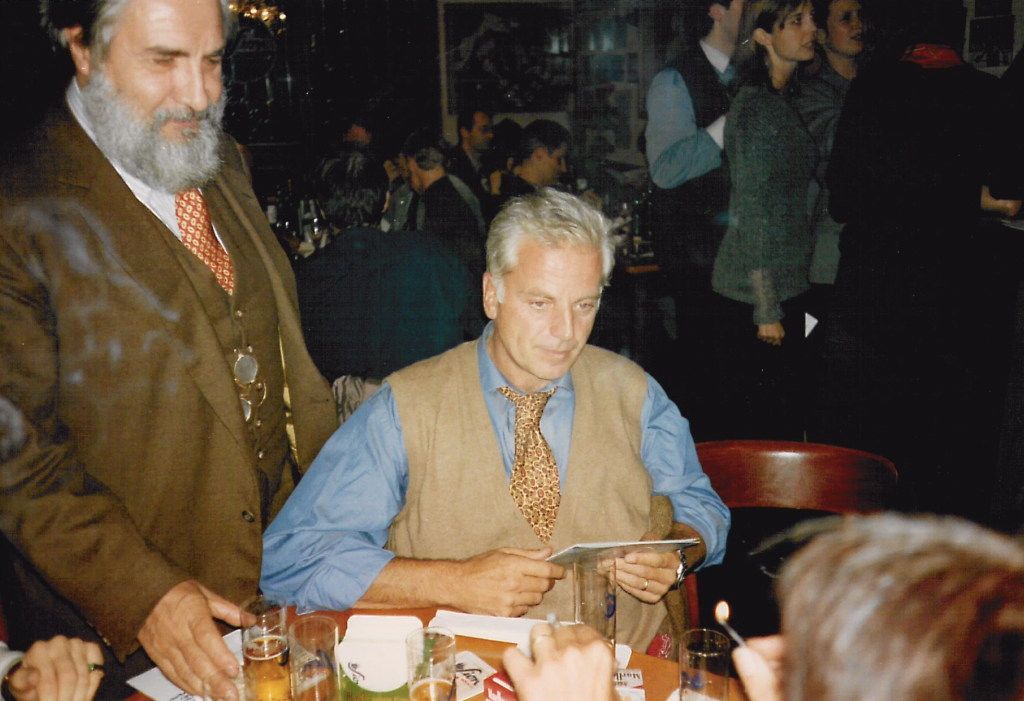

Contemporary art dealer Bruno Brunnet (left in both pictures) and Michel Würthle. Photo courtesy of Bruno Brunnet

Then, there are the artworks that loom around this clientele. A large-scale oil painting by Neue Wilde painter Jörg Immendorff above one dinner table depicts Würthle in an unbuttoned green shirt, sitting in a surrealist landscape as goblin-like figures look on. It is intriguing and weird and, like everything in this bar, seemingly part of a running inside joke; some who dine here do so because they want to be in on it.

A hand-drawn birthday card from the conceptual artist, fellow Austrian expat, and best friend of Würthle, Martin Kippenberger, is framed in another corner (“ciao mega art baby!” it reads). Across the room, a framed photograph of Yves Saint Laurent runs halfway up the wall behind a booth, signed by the designer and affectionately addressed: to Paris Bar. A self-portrait by Sarah Lucas, dangling an impotent-looking cigarette on her lips, presides over a sea of what might be a hundred or more pieces of art. The collection was assembled largely by Würthle: some are doting gifts given to him, other works were exchanged for food, some were purchased, and there is barely an inch of wall space between them.

If this bar is a Berlin cultural outpost, which those who love it will devoutly argue that it is, then Würthle was a cultural ambassador. He died in mid-March at the age of 79 after a battle with cancer that, according to his friends, began sometime around 2018. He leaves behind his life partner, Katherine Kaaris, and a daughter from his first marriage, Karolina.

Gotthard Graubner & Michel Würthle. Warme Mahlzeit, Cologne, 1993. Image: Bruno Brunnet

Before his illness took a turn for the worst, he was at his restaurant nearly every day since opening it in 1979 on the west side of a then-divided city. He was there, cultivating his ideal of a cultural scene that also included actors, literati, and people he liked.

Würthle was known to be a sharp-tongued dandy type who conveyed old world elegance with an air of bohemian grit. He was also an artist had a dedicated practice of drawing as well as uncanny collaborations with friends. His humorous and witty character garnered him low-key celebrity status. He was “an elegant man,” as artist and friend Daniel Richter described him, who could make “complicated things look very simple.”

One could say Würthle’s craft was to create a myth out of the bar, the art, and the people in it. Put another way by Bruno Brunnet, an art dealer and close friend of the restaurant owner and one of the bar’s unofficial cultural attachés, it is a social sculpture. “If you are from our tribe, you are going to meet someone there. You are not alone,” said Brunnet over the phone a few days after his friend’s death. “That was Michel’s job, that was his creation.” Whatever it is, it was the life’s work of Michel Würthle, and he was, without a doubt, an artist.

Austrian restaurant owners of Paris Bar, Reinald Noahl (right) and Würhle (left). Photo by XAMAXullstein bild via Getty Images)

The Mythmaker

In a feature published last year in Der Spiegel, Würthle summed up his views about what a restaurant should be. “Oh, well,” he said. “[I]t should be world-famous. And good. And crappy. Above all, unique.” He disliked the term “artist bar,” though that remains the easiest way to describe what Paris Bar is. “But of course it’s quite important that artists are there,” he said. “But as few politicians as possible. And actors are needed, who are admired.”

A devoted crowd of those who knew him best gathered at Paris Bar in late March for a memorial. I had eaten there with friends the night before with a large photograph of Würthle in a cowboy hat in view. That night, the restaurant was packed, as usual, but with a note of gravitas in the air. People on the outer circles of the Paris Bar scene had all booked tables to say their goodbyes. The following evening, Würthle’s good friends came together to take over the restaurant, eat Austrian food, and drink a lot of wine in his memory. The mood was melancholic but bright, according to Richter. Brunnet made a speech, as did the painter Markus Lüpertz.

If you spotted Würthle at Paris Bar, you would have seen him chatting with guests, emptying ashtrays, instructing waiters, and throwing raucous post-opening art parties where, sometimes, people took their shirts off. A formidable host, though he was known to kick out some guests to make room for others he deemed more important (whoever said the art world had to be fair?). Celebrities clustered in his midst: Robert De Niro and Jack Nicholson are among those reported to have pulled out chairs across the checkered floors. Yoko Ono and Nelson Mandela have been photographed at its parties. Leonardo DiCaprio’s and Damien Hirst’s names are in the guestbook, and so on.

Paris Bar in 1986. Photo by Günter Schneider/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Around the restaurant, a slew of manifestos are hidden: on its current menu, a very small, nearly imperceptible cursive type: “meeting place for the intellectual and artistic elites” is printed. On the doorstep, a subtly placed stone doormat engraved with “passerby, be modern” goes largely unnoticed. In Berlin, a city that is rapidly transforming, caught between a techno hub and spawning ground for tech startups, a place like Paris Bar may pull you delightfully out of time, even if just for a meal.

Würthle took over Paris Bar in his mid-30s, in 1979, with a childhood friend and Austrian, the equally well-dressed, art-loving Reinald Nohal (he died last year, in August). At the time, Würthle was running another bar on the other side of town called Exile with his friends, artists Ingrid and Oswald Wiener in the ground floor of an apartment building where he also lived, on a wide canal in a bustling area of Kreuzberg. Exile, like Paris Bar, had white tablecloths. Helmut Newton hung out there, as did Joseph Beuys. Kippenberger, whose own celebrity in the art world was exploding at the time and who was the closest to Würthle, as well as Dieter Roth, hung out at Exile too, where they never had to pay any bills because they paid him in art, a ritual that moved over to Paris Bar when it opened. Unsurprisingly, Würthle acquired a rather enormous amount of Kippenberger’s art and drawings.

Their new hangout was an old French bar originally opened by a man from Lyon who had been a cook for Berlin’s French occupation forces. Back then, the bar had been frequented by art students, who strolled over from the nearby University of Fine Arts, as they still do. “Würthle and Nohal made some money and were looking for a new adventure,” recalled Brunnet. There was also the fact that his friend had spent years in Paris, where he had appropriated an air of French savoir-faire (Michel’s birth name is actually Michael and the French pronunciation was adopted) and the particularities of his Austrian style were refreshing among the Berlin set, which, tends to be more austere, known rather for its “Berlin snout” than its grace or its cuisine.

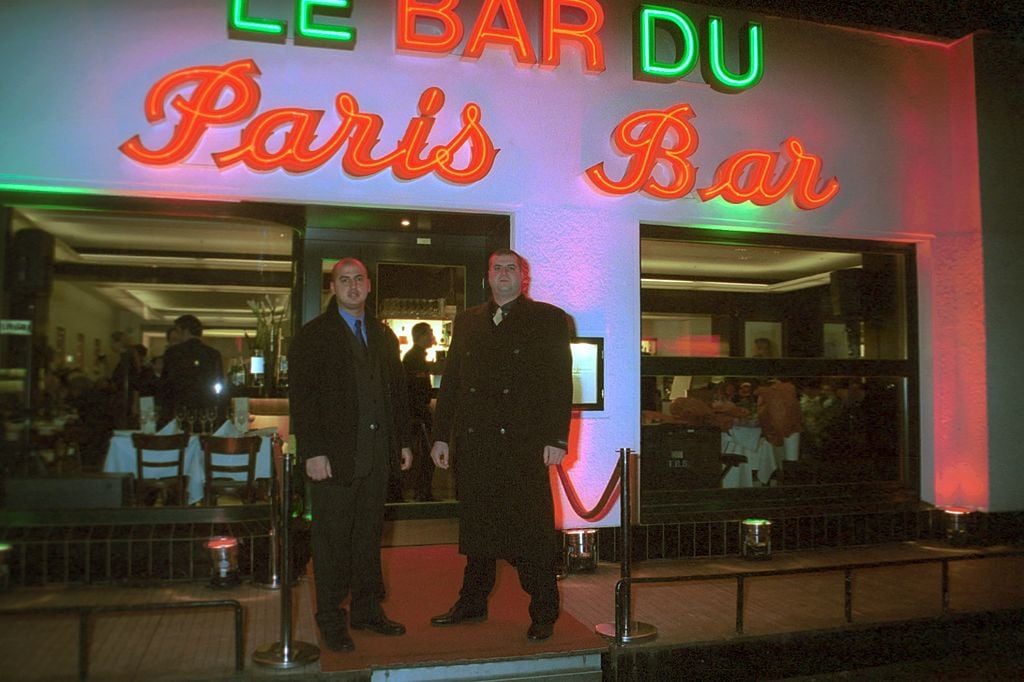

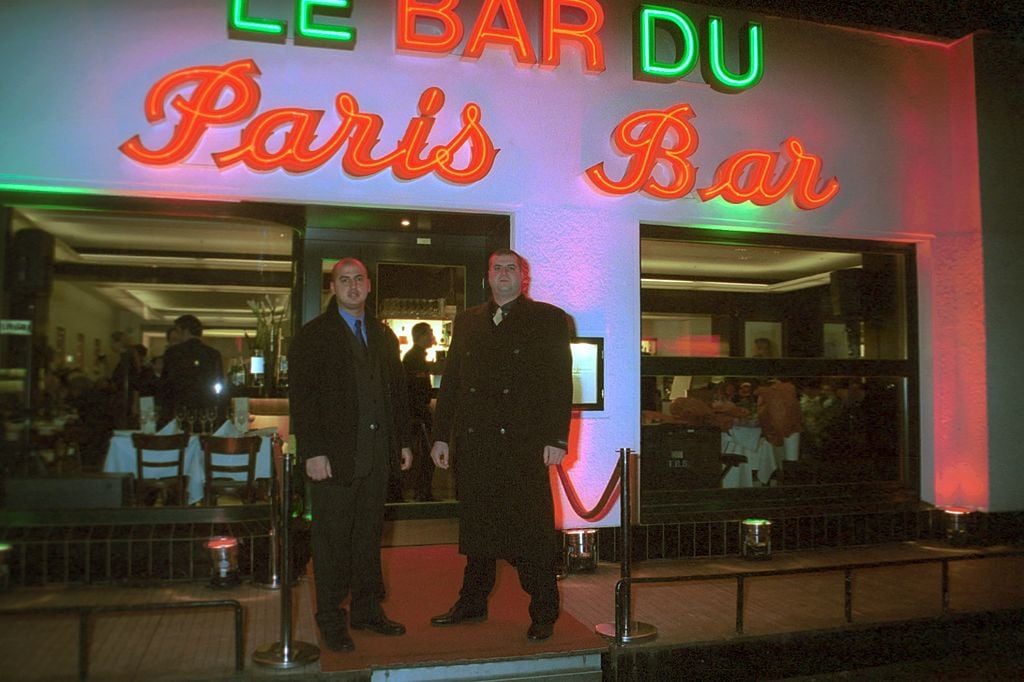

Bodyguards outside for the 50th birthday party of actor and singer Angelika Milster. Photo: Peter Bischoff/Getty Images

Würthle and Nohal took over the name and the classic French fare. Its waiters today still tote out onion soup and salat niçoise. If they like you—you will know. There’s no music inside Paris Bar and there never was—the soundscape is boisterous conversation in German, English, and rarely ever any French, which may heighten the chance for interactions between tables. Waiters hover or lean on a tall bar stained a dark reddish brown in the early evening before the dinner rush, enjoying a cappuccino. During the balmiest months of summer when the sun sets directly in line with Kantstrasse—rue Kant as a neon states on the exterior wall—a waiter might be seen smoking on the street side, not far from the patio. Würthle would have had a table outside smoking, years ago, as those who knew him recalled, keeping an eye on the garçons as he called them (the servers, like many of its inner circle, are male).

Dealer Bruno Brunnet, who co-runs the gallery Contemporary Fine Arts, was a first generation regular well before he founded his gallery with his wife, Nicole Hackert. A rotation of Contemporary Fine Arts’s exhibition posters—from a roster of artists that includes Tal R, Georg Baselitz, and Dana Schutz—are a staple feature of the bar, attached to the sloped window by the front door. Kippenberger introduced Brunnet to Würthle at a performance at Cafe Einstein in 1979, and he was hired on the spot to be a server at Exile. Years later, Hackert and Brunnet were married in Paris Bar. Occasionally, at night, if the jukebox does go on, Brunnet is among the very few permitted to command it.

Paris Bar. Photo courtesy Ernst Arno Baur.

Artist Christopher Williams recalled how, when he’d come to Berlin for a show in the 1990s, Galerie Gisela Capitain had arranged a post-opening dinner party for 15 people and Paris Bar was the venue. “I’d mis-gauged how many friends and colleagues I had in Berlin at that point. An enormous amount of people showed up and it was hard to tell them that we could not accommodate them.” Gisela Capitain called Würthle. By the time they arrived at the bar with a party that had spiraled to around 50 friends, Michel was there, “literally kicking people out with a raised voice and language I won’t use,” Williams recalled. “He told them all they got free drinks, some free food, but that there was an artist who needed a place to have an opening dinner. That it was his bar, and that they could take it or leave it.”

After clearing out the room of its surprised guests, Würthle poured red wine for the groups. “By 21st-century standards, it is a little funny in terms of privilege,” Williams noted. “But everybody had a really memorable, fantastic evening.”

How much should one memorialize a place that has a hierarchy built into it? Like the art on its walls, the guests at Paris Bar are curated by a familial ethos: there are favorites, black sheep, father figures, and those who don’t fit in. “Würthle treated people by their attitude and not by their fame,” noted Richter. “You could be famous, but if you were too vulgar or nouveau riche, he did not feel the need to be very nice to you.” There is new young money there now, the same unavoidable kind that is flowing into Berlin, but it must compete for the few tables available for those outside the dedicated scene and regulars. And local lore has it that even Madonna did not get the table she wanted once.

Würthle was incredibly generous especially with artists. Beyond dinner parties, the bar is used variously as an office space, a creative retreat, or lecture room made available on early mornings before it opened. “There was never a question about how we were using the table or when we would leave,” Williams said. “I think this shows his value system.”

That focus on creativity transcended the art world. In a now-famed Rolling Stone feature by Chris Hodenfield from 1979, called “The Bad Boys of Berlin,” he followed David Bowie and Iggy Pop around the city streets. Naturally, they led him to Paris Bar where Iggy Pop was often found “folded into a booth,” the writer described, “a subdued green room holding a few green souls,” who “had all stepped right out of Van Gogh’s The Absinth Drinkers.”

“It was real art,” Hodenfield wrote of the scene, adding “if you could tolerate it.”

Martin Kippenberger and Michel Würthle, Syros, Greece, (1993). Photographer unknown, courtesy Estate of Martin Kippenberger, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

The Artist

But was it art then? Is it now?

Maybe the answer is in Greece, at a subway station entrance that leads to nowhere, which has never been opened. The surrealist metro stop on the island of Syros is the first of Martin Kippenberger’s acclaimed METRO-Net World Connection, one of his major last works across multiple cities made between 1993 and 1997, the year he died.

The one in Syros, which was the first, was built on Würthle’s property there. The concrete sculpture, complete with stairs, guardrail, and fake advertisments (one is an ad for an Immendorff show at Michael Werner Gallery) has a locked gate at the entrance. The stops seem to search for another way to be in the world, mock the myth of a globally interlinked society. It would have had a particular poignancy and astuteness in the wake of German reunification a few years earlier.

The second stop Kippenberger made is tens of thousands of kilometers away in Dawson City, a remote frontier town in northern Canada, on the summer property of Nohal, the other owner of Paris Bar. The three locations including the bar were dubbed the Bermuda Triangle. In a book about the project the planning was published “should anyone decide to do the rest of the underground excavation and construction.” The ambition of the stops of METRO-net show the sense of collaboration Würthle (and Nohal) had with artists they liked, as well as the intellectual proximity they shared with Kippenberger in particular.

Exhibition view Michel Würthle | Elfie Semotan „Ein verlorener Haufen kehrt zurück“, Galerie Crone Wien, 2017, Courtesy Galerie Crone, Berlin Vienna, Photo: Matthias Bildstein. Photo „John“, 2017: © Josef Fischnaller.

Between Berlin and Syros, Würthle began to make his own art, in the 1990s, both with his artist friends and on his own, often in the form of drawings. He created diaristic documents of his scene, including the bar’s changing menus and the manifold characters in his life that are cheeky and touching. Galerie Crone in Vienna presented an exhibition of work with Elfie Semotan. Some years later, Richter and Würthle did a show of collaborative paintings with intentionally blurred authorship. Also blurry was the separation of the bar business and the artwork.

“His art was always important to him, but Paris Bar was always a part of it,” noted Brunnet. The mythology Würthle created around him was all a gesamtkunstwerk; and this was on view Paris Bar Press Confidential, a sumptuous catalog he made that came out in early 2022. Then, Anna Ballestrem, from the auction house Grisebach, invited Würthle to have a carte blanche to organize a sale and exhibition last fall. He called the show “Feeling and Understanding,” which Ballestrem said was “unexpected of him.” His illness was progressing at the time. On view were works he made alone, with other artists, and memorabilia, and pieces of his Berlin apartment—he even brought his wooden wardrobe to include in the show and, even though he may not have been feeling well, came back continually to make adjustments. “It was his soul he showed,” said Ballestrem, who described him as an outsider artist. “He knew how sick he was.” The room the night of the sale was packed. Afterwards, they went to Paris Bar.

Contemporary Fine Arts, who organized a show of Würthle’s in 2019, will have a posthumous exhibition in his memory for his 80th birthday in September.

Paris Bar by Daniel Richter. Photo by Kate Brown.

An Everlasting Picture of Paris Bar

Nothing in the art Würthle made or surrounded himself with defines his art collection and character as much as another work by his friend Kippenberger; a large painting of the bar. By now, it is even more iconic than the subject matter it depicts. Kippenberger painted the restaurant to the left wing of the bar, mirroring the room with its Frankfurt-style wooden chairs and napkins folded into pyramid shapes, the tables empty of diners. The mise-en-abyme was hung in the bar on the back wall of the right wing, reflecting the ongoing cheeky estrangement and witticism promoted by its inner circle, and which is signature of Kippenberger.

Four more exist, floating around in private collections and each is a riff on the other—their inside joke rolling onwards. The 1991 artwork that hung there first is no longer on the nails: Würthle sold it, and it later made its way to the auction market in 2009, selling for a cool £2.2 million at Christie’s. Dutifully, Kippenberger made Würthle another in 1993, but it was sold too, and ended up at auction at Phillips de Pury & Company in 2007, selling for £636,000. That one is now in the Pinault Collection in France. Then, a work made “after Kippenberger” was made for Würthle by Richter. In Richter’s work, the paintings hanging about the tables are different. Versions of versions—self-canonization via serialization.

But even that one is gone now too. Richter’s copy of the Kippenberger copy went on tour in a show about the deceased artist’s influence, and never returned. Up in its place went collaborative work by Jonathan Meese and Albert Oehlen, and Richter kept asking Würthle when his work would back on the wall. Michel shrugged it off and said it was coming back soon enough. This went on for one or two years until, finally, Richter ran into a collector in Berlin, Folker Skulima. “[He] told me how happy he was to have my work because it was full of memories of Paris Bar,” Richter recalled, and he pretended to know what Skulima was talking about. Michel had sold it to him because he needed some money. “I was a little angry, but then I realized if I am angry I cannot go to the bar anymore. I decided to punish my friend with love.” Just like Kippenberger, he made him another painting, and he eats and drinks for free. “It’s a good deal,” Richter said.

Exhibition view Michel Würthle | Elfie Semotan „Ein verlorener Haufen kehrt zurück“, Galerie Crone Wien, 2017, Courtesy Galerie Crone, Berlin Vienna, Photo: Matthias Bildstein. Photo „John“, 2017: © Josef Fischnaller.

The Kippenberger and Richter paintings were not sold out of lack of love, but rather necessity. Money troubles arose for Würthle and Nohal more than once. The restaurant industry is a business with tight overheads, and this crew also seemed to live large and have a lot of fun. They were not taking care of their paperwork appropriately: In 2011, Würthle and Nohal were taken to court accused of tax evasion to the tune of €2.9 million between 2001 and 2005.

At the hearing, Nohal and Würthle confessed. Nohal admitted the place “was poorly managed” and Würthle, according to a report in the Berliner Morgenpost from the time, told the court that the two had to repeatedly borrow money to “plug the holes in the cash register” and “even had to sell paintings that friends from the art scene had given them.”

More astounding then the multi-million euro fumble was the outcome in court. Each were given suspended jail sentences of two years, essentially, a slap on the wrists. In his ruling, the judge noted the duo were not “typical tax evaders” looking to hide money in Mallorca. “In the bar, they found a system and continued it, which, according to a tax investigator, is unfortunately common in Berlin,” the judge said, according to reports.

Martin Kippenberger, MOMAS. Museum of Modern Art Syros, Greece, (1992/93). © Lukas Baumewerd and Estate of Martin Kippenberger, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne. Photo: Lukas Baumewerd

A journalist writing in Berliner Morgenpost at the time said, the duo, who “obviously know more about art than about accounting” were forced to declare insolvency and had to give up the restaurant. The judge sounds nearly affectionate in describing Nohal and Würthle: “two older men who to a certain extent have rendered outstanding services to Berlin culture… now facing the ruins of their bourgeois existence.”

Not much visibly changed, at least from the perspective of the guests. A fellow restauranteur, Ernst Arno Baur, was entrusted with the reins, but Würthle was hired as an employee. He still worked the door, and by most measures (except on the books) was a boss, and the restaurant’s heart and soul, according to regulars I spoke with. And that continued on for more than another decade—Würthle’s ease, charisma, and dry humor remained a fixture of Paris Bar.

Last weekend, just as the buds began peeking out in Austria, Würthle’s funeral was held in the region of Burgenland, a place known for its good wine. His dear friend, Austrian sculptor Walter Pichler, is buried just beside him. And just one hill over, never far from place or mind from Würthle, Kippenberger is resting. This wild metro line has made a final stop. But over in Berlin, Paris Bar is pouring out another drink.