Museums & Institutions

Demonstrators Descend on the British Museum to Make the Case for Athens as the Rightful—and Safer—Home for the Parthenon Marbles

The demonstration marked the 13th anniversary of the opening of the Acropolis Museum in Athens.

The demonstration marked the 13th anniversary of the opening of the Acropolis Museum in Athens.

Cristina Ruiz

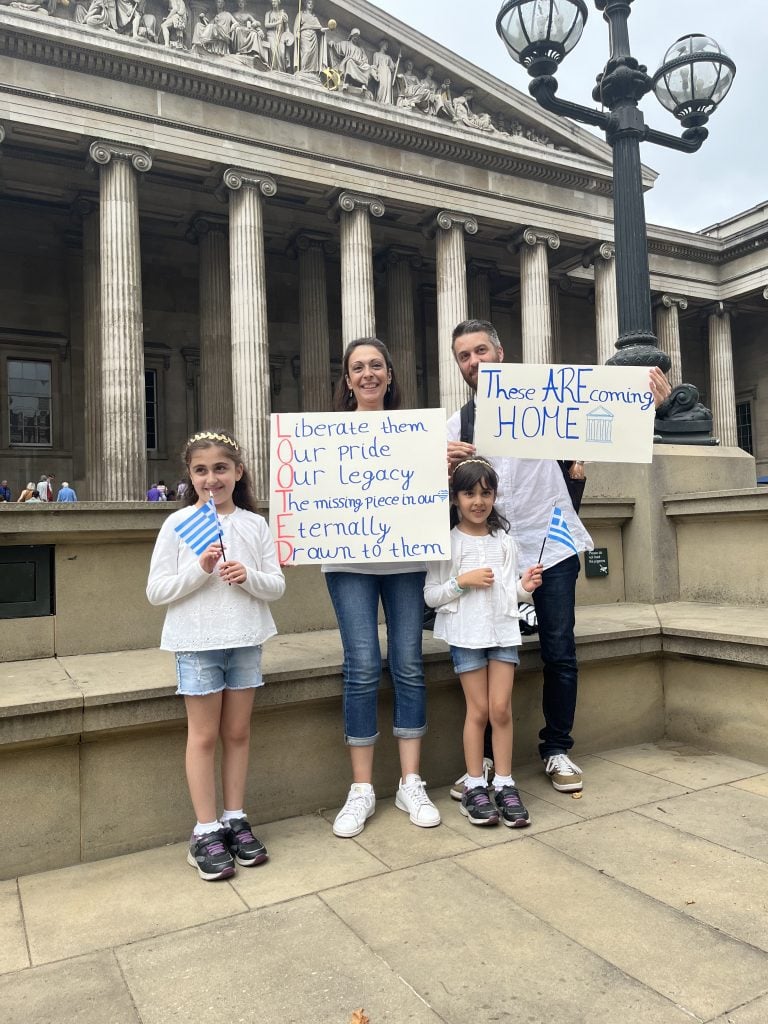

Campaigners gathered at the British Museum in London on Saturday to renew calls for the institution to return its Parthenon Marbles to Greece.

The ancient sculptures, which were removed from the Acropolis by Lord Elgin in the early 19th century, are housed today in a gallery that is “dark, wet, and has leaks in the ceiling,” George Gabriel of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles told fellow activists as he welcomed them to the British Museum’s Great Court at the start of the demonstration.

“This is a long story of how the marbles were taken wrongly, cared for badly, and should be returned,” he added.

The event was organized to mark the anniversary of the opening of the Acropolis Museum in Athens 13 years ago in a new building designed by the French-Swiss architect Bernard Tschumi, which is located just 300 meters from the Parthenon and its surrounding buildings and monuments.

Around 50 intergenerational activists attended the demonstration, which was organized by the Reunification Committee and included Greek and British supporters, classicists, and professors. The crowd grew in size as it moved from the Great Court to the Parthenon Gallery, attracting members of the public along the way. The protest took place with the full consent of the museum.

Activist Marlen Godwin calls on the British Museum to be more open and truthful in its account of how Lord Elgin removed the sculptures from Greece. Photo: Cristina Ruiz

The Acropolis Museum is “the rightful home of the sculptures,” Gabriel said.

The Greek museum “is five times, a million times, better [for the display of the Parthenon Marbles] than here,” Edith Hall, a professor in the department of classics and ancient history at Durham University, told the crowd of activists. “It’s a no-brainer and I actually believe that, in my lifetime, these marbles will be returned.”

One of the British Museum’s traditional justifications for retaining the sculptures has been “that they are a world museum and have a duty to show the marbles. How imperialist does that sound to the young generation? The argument just doesn’t work anymore,” she added.

There were cheers and chants of “send them home” as the protestors moved into the Parthenon Gallery where they unfurled banners, posters, and Greek flags. The mood was boisterous, even jubilant, as activists responded to comments made by George Osborne, the chairman of the trustees of the British Museum, just four days earlier, which appear to signal a shift in the way museum leadership is thinking about the sculptures.

In an interview with LBC radio on June 14, Osborne said “there is a deal to be done” with Greece over the future of the fifth-century B.C. sculptures housed in the British Museum “where we can tell both stories in Athens and in London if we both approach this without a load of preconditions, without a load of red lines,” he said.

Although the activists welcomed Osborne’s comments, they rejected suggestions that Greece and Britain might be able to share the marbles. “The British Museum hasn’t realized that there aren’t two stories to be told about the Parthenon sculptures; there is only a new chapter, and the new chapter is in the Acropolis Museum,” said Marlen Godwin of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles.

A door in the Parthenon gallery leading to an external museum space was wide open on June 17 and 18. Photo: Cristina Ruiz

Asked about the British Museum’s current position, a spokesperson told Artnet News that its goal was and remains public access. “The museum is always willing to consider requests to borrow any objects from the collection, we lend between 4,000–5,000 objects every year,” she said. “These beautiful works of art are loved by a world-wide community and we believe that public access should lie at the heart of these conversations, too often discussions are limited to legalistic and adversarial context instead of focusing on how to share the sculptures with a wider world.”

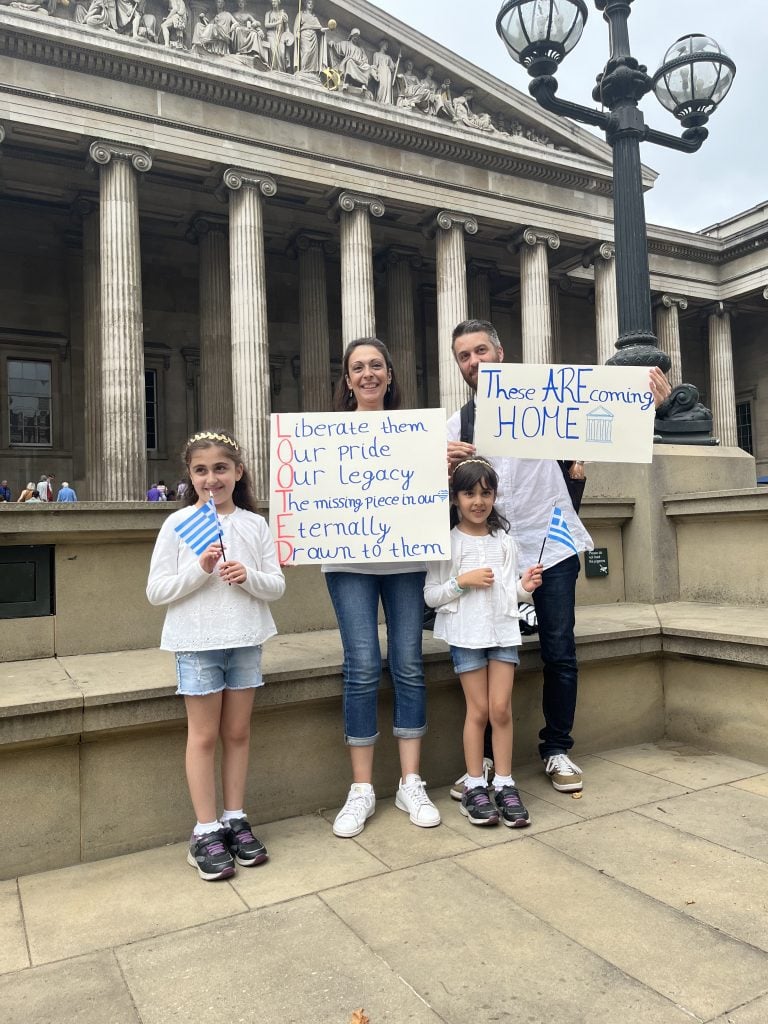

As activists extolled the state-of-the-art facilities of the Athens museum, the poor conditions in the British Museum’s own Parthenon Gallery were on display: a door leading to an external museum space was wide open, presumably to increase ventilation, and three fans were positioned at the South and North ends of the space.

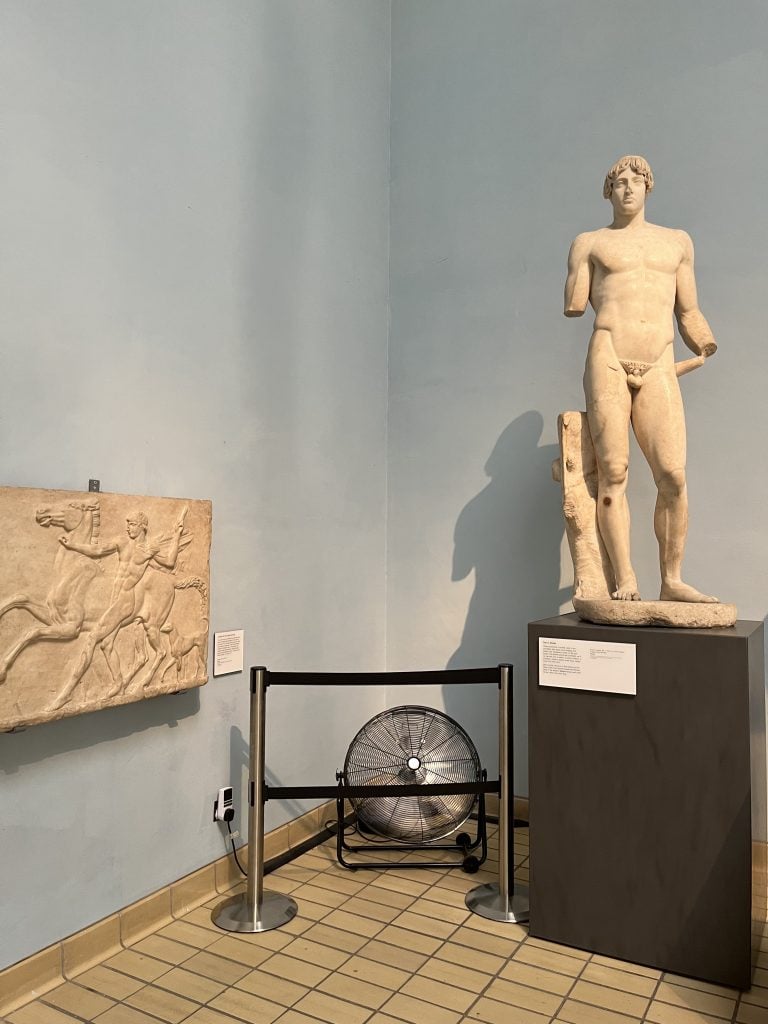

The British Museum has placed 15 fans in its Greek, Assyrian and Egyptian galleries to help increase poor ventilation in the block. Photo: Cristina Ruiz

The Parthenon Gallery is located in the oldest part of the museum, the Western block, which comprises the Greek and Assyrian displays and part of the Egyptian collection. Artnet News visited all the galleries in the block on June 17 and 18 and counted 15 fans positioned among the ancient sculptures on both days, a lo-fi effort to correct inadequate air circulation.

Next door to the Parthenon Gallery, access to the Nereid Monument, a sculpted 4th-century B.C. tomb of a Lycian leader, is partially obstructed by scaffolding that reaches the gallery’s ceiling. A sign posted on the scaffolding reads: “The British Museum’s complex, historic site—with parts dating from 1823—requires regular maintenance, renewal, and refurbishment. We are currently carrying out a program of work to maintain the building, protect the collection and improve the visitor experience.”

The museum declined to specify why this specific scaffolding is in place. The roof in the same gallery leaked in July 2021 after heavy rainfall.

The Nereid Monument at the British Museum. Photo: Cristina Ruiz

In response to questions about the condition of the galleries, a British Museum spokesperson said: “The museum is an historic and listed building and there are ongoing infrastructure assessments across the site. The care of the collection and the safety of our visitors and staff are our utmost priority.”

The poor conditions of the British Museum’s Western block have been recorded multiple times. In 2018, Greek television broadcast images of water dripping into the Parthenon gallery. The leak was caused by a 40-year-old glass ceiling pane cracking, the museum said. The glass was replaced with new fixings and no sculptures were damaged, the museum added.

Nevertheless, the Greek culture minister Lina Mendoni noted at the time that the leak “reinforces Greece’s rightful demand for the sculptures’ permanent return to Athens.”