Art World

Partition Museum Opens Near India-Pakistan Border, Ending Decades of Silence

The deadly postcolonial upheaval will be memorialized through archives, personal effects, and art.

The deadly postcolonial upheaval will be memorialized through archives, personal effects, and art.

Brian Boucher

Seventy years after one of the most deadly and disruptive political cataclysms of modern times, the Partition Museum has opened in the Indian city of Amritsar. It is the first cultural institution dedicated to the postcolonial partition of India and Pakistan.

The museum is sited just 12 miles from the Wagah border crossing with Pakistan, known for a daily military parade staged by India’s border security force and the Pakistan Rangers, a testament to ongoing tension between the two nations.

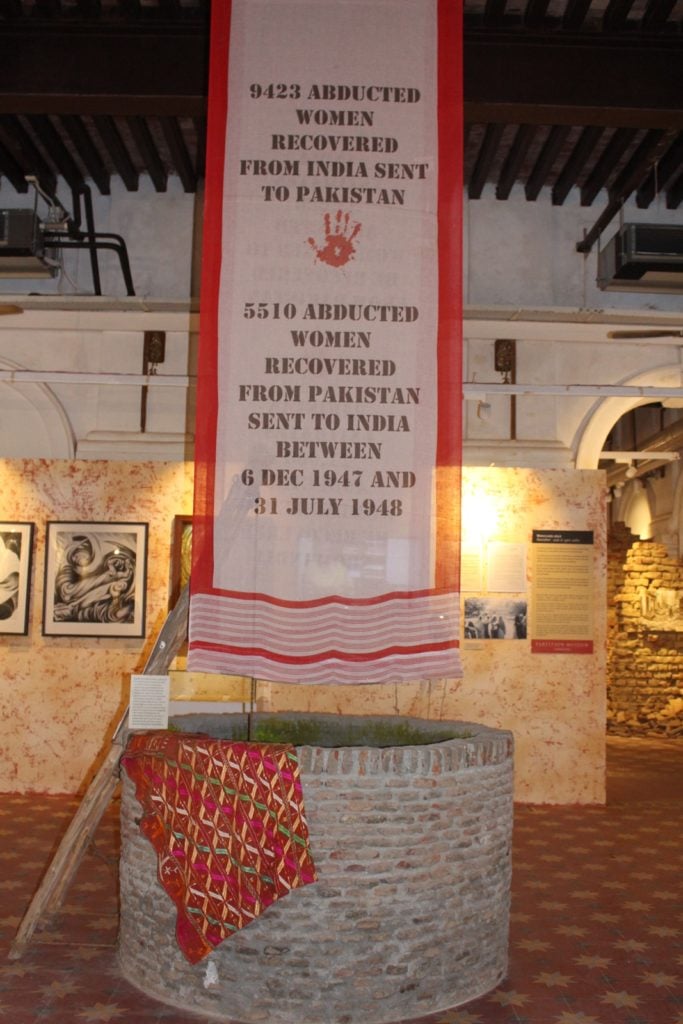

The 17,000-square-foot space in a brick town hall building donated by the Punjab government houses personal effects from families affected by the forced migration, archival documents, and never-before-seen works of art and photographs. It memorializes a bloody chapter that began on August 17, 1947, when British officials announced the hastily drawn border between the newly independent Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan, leaving millions of people unsure which country they were actually in.

By the museum’s estimate, some 20 million souls were forced to migrate across the border in either direction and uncounted thousands died in clashes between Muslims and Hindus. Many more were raped or beaten.

The trauma of Partition has not been addressed in any thorough, permanent, and public way, say the museum’s organizers, a group that includes Indian novelist and former journalist Kishwar Desai. Artist and nuclear weapons activist Salima Hashmi and publisher Jugnu Mohsin served on an advisory committee.

A visitor to the new Partition museum, Amritsar, India. Photo courtesy Partition Museum.

In an interview, Desai noted that while there are museums devoted to other historical traumas like the Holocaust and harrowing events like the 9/11 attacks, the particular history of the cleaving of the two states presented a unique and critical subject. Writing in the Guardian, South Asia correspondent Michael Safi describes an “official amnesia” over the events.

The nonprofit organization that supports the museum, the Arts and Cultural Heritage Trust, was established just two years ago, with the tight deadline of opening the new museum on the 70th anniversary of Partition.

Art plays a role in the galleries, including works by well-known artists like Satish Gujral (who also serves on the museum’s board), Krishen Khanna, and Sardari Lal Parasher. Parasher spent time in a refugee camp, said Desai, and, having escaped with only the clothing on his back, resorted to drawing in everyday notebooks or other unconventional surfaces using charcoal and even earth. In keeping with the silence around Partition, these works, which offer rare artistic documentation of the lives of refugees, have never before been exhibited.

An exhibit at the new Partition Museum, in Amritsar, India.

In crafting a narrative from these diverse materials, Desai drew on her experience as a journalist and novelist. “I’m used to storytelling, and I worked in television for 35 years, so I have worked with visual material all the time,” she said.

Though the journey through the history of Partition may be disturbing for many viewers, the experience ends on a hopeful note, Desai said, with a gallery that invites visitors to leave messages on leaf-shaped paper and hang them from a wire tree.

The museum’s collection, Desai added, is still in its infancy. She hopes the opening will spur more donations and oral histories, bringing more stories into the light of day.