Art World

A French Artist Is Under Fire for Hanging a ‘Disrespectful’ Replica Skeleton of Napoleon’s Horse Over the Military Leader’s Tomb

The sculpture is part of an exhibition marking the bicentenary of Napoleon’s death.

The sculpture is part of an exhibition marking the bicentenary of Napoleon’s death.

Anna Sansom

As France commemorates the bicentenary of Napoleon’s death this month, members of the French establishment have lambasted the artist Pascal Convert for suspending a replica skeleton of Napoleon’s horse above the former emperor’s tomb in the dome of the Invalides in Paris. Critics say that the artwork, created for an exhibition about the military leader, is “disrespectful.”

Titled Memento Marengo (2021), the sculpture is based on 3D scans of Napoleon’s favorite horse at the National Army Museum in London. Convert was commissioned to make the piece for a group exhibition at the Musée de l’Armée. Curated by the French art historian Eric de Chassey, “Napoleon? Encore!”, opens on May 19.

The artwork immortalizing the French military leader’s loyal steed has enraged several historians and politicians. Historian Thierry Lentz, director of the Napoleon Foundation, wrote on Twitter: “This is not a way to honor our dead,” while another member of the foundation, Pierre Branda, dubbed it “a grotesque and disrespectful idea” in an op-ed for the French paper Le Figaro. Meanwhile, a member of the French parliament, Jean-Louis Thiériot, called the idea “crazy.”

But Convert, who previously made a photographic project about the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas by the Taliban, has defended his work. “I’m an artist who works on death, not on provocation,” he told Artnet News.

Retorting to his critics, he said that the piece refers to sacred rituals. “Horses have been buried in warriors’ tombs since antiquity in China, and I discovered an image taken in the Altai mountains in Central Asia of the skin of a horse hanging by poles, forming a pyramid over a tomb,” he said. “On the bicentenary of Napoleon’s death, I found that there was the idea of voyage, with the horse returning to the tomb of its horseman.”

Convert was initially struck by the depictions of horses in battle in a painting by Louis-François Lejeune, which led him to research Marengo’s skeleton. The grey Arabian horse was captured at Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, brought to England and displayed as a war trophy. Upon seeing its skeletal image, Convert had the vision to have the horse hovering, “like a ghostly apparition”, above Napoleon’s tomb.

The French artist hired a start-up to make the 3D scan but was unable to visit London’s National Army Museum to see Marengo’s skeleton in person due to lockdown. “As soon as the [health] measures ease up, I’ll go,” he said.

The Musée de l’Armée has also defended Convert’s work. “Artists are there to react and question; their approach is close to that of historians, it’s not to bring solutions but to question facts and characters,” said Ariane James-Sarazin, the museum’s deputy director.

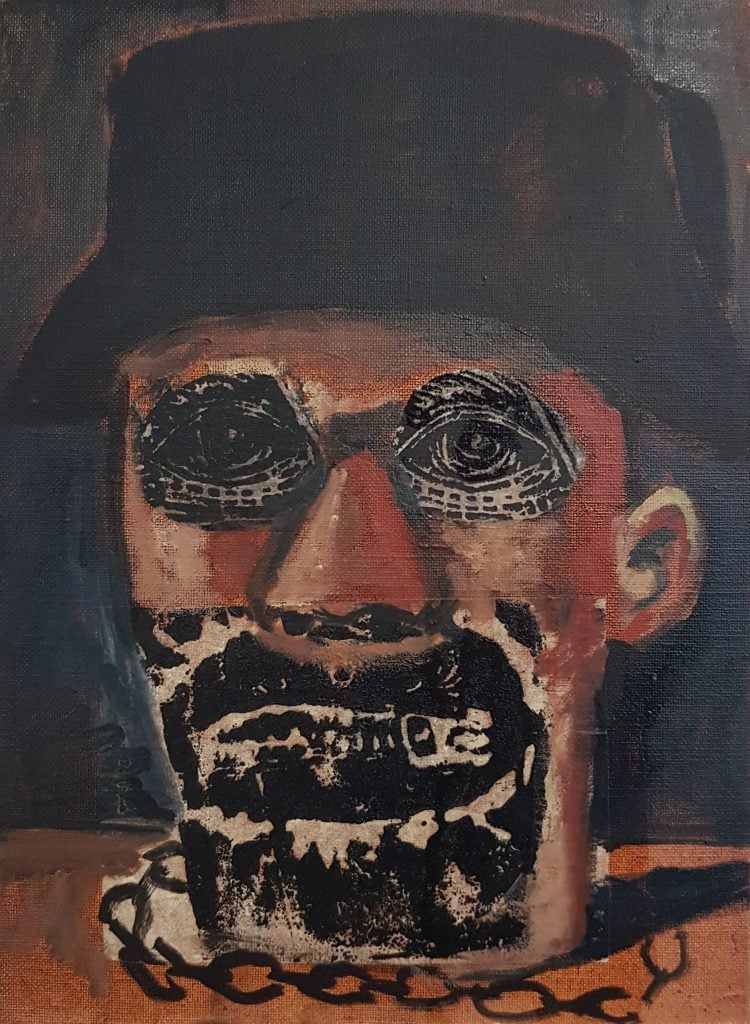

Damien Deroubaix, 20.V.1802 (2020). ©Courtesy galerie In situ – Fabienne Leclerc / D.R. / Adagp, Paris 2021.

Among the 27 artists included in the exhibition are Yan Pei-Ming, Marina Abramović and Julian Schnabel, whose works are dotted throughout the museum. Many of them have avoided addressing how Napoleon reinstated slavery in 1802 after its post-revolutionary abolition in 1794. Yet the painter Damien Deroubaix tackles this in his painting 20.V.1802 (2020), titled after the reinstatement date. It portrays the face of a Black man wearing Napoleon’s bicorne hat and an unbroken chain around his neck.

Meanwhile, Kapwani Kiwanga, who won the prestigious Prix Marcel Duchamp contemporary art prize last year, alludes to the Haitian Revolution in her embroidered textile work Nations, Snake Gully, 1802 (2018). Composed of several banners, it draws on the Voodoo, African, Catholic and Indigenous aspects of identity and history in Haiti, which was colonized by the French. “I wanted to question what is a nation, what is a flag and reflect upon conflict, war and the complexity of what a nation can be,” said Kiwanga, one of only seven women artists in the exhibition.

By contrast, Ange Leccia’s multi-screen video installation of a natural landscape reflects on Napoleon’s birthplace of Corsica and his later exile on the island of St. Helena. “I couldn’t go to St. Helena during the pandemic so I went to Corsica, where I’m lucky to live close to the sea, and imagined Napoleon thinking about his life and how nature supersedes mankind,” Leccia said.

Several other exhibitions about Napoleon are taking place concurrently. Also at the Musée de l’Armée, “Napoléon n’est plus” (Napoleon is no more) features historical paintings and memorabilia, while another exhibition at the Grande Halle de La Villette in Paris explores the military leader’s “complex character.”