Archaeology & History

Patagonia’s Cueva Huenul Cave Art Is Thousands of Years Older Than Previously Thought

Researchers say that designs could be over 8,000 years old.

Researchers say that designs could be over 8,000 years old.

Verity Babbs

New research has found that cave art in Patagonia’s Cueva Huenul 1 cave is several thousand years older than expected, and is now the oldest known artwork in the region. The rock art had previously been dated as just a few thousand years old, but new analysis published on February 14 in Science Advances has found that a set of comb-shaped designs on the wall are likely to have been created 8,200 years ago. Patagonia lies at the southernmost tip of South America, spread across Argentina and Chile who both govern the region.

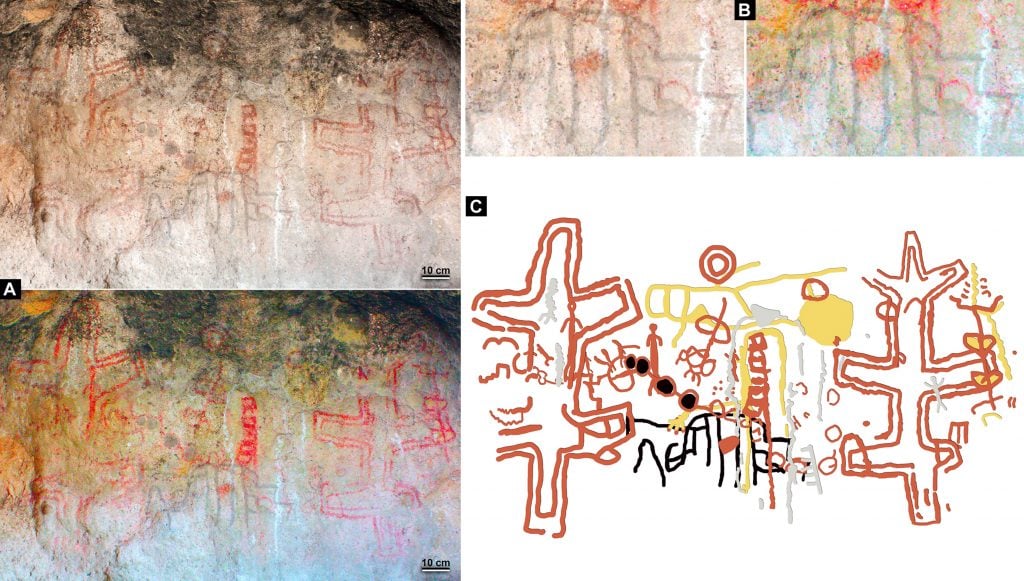

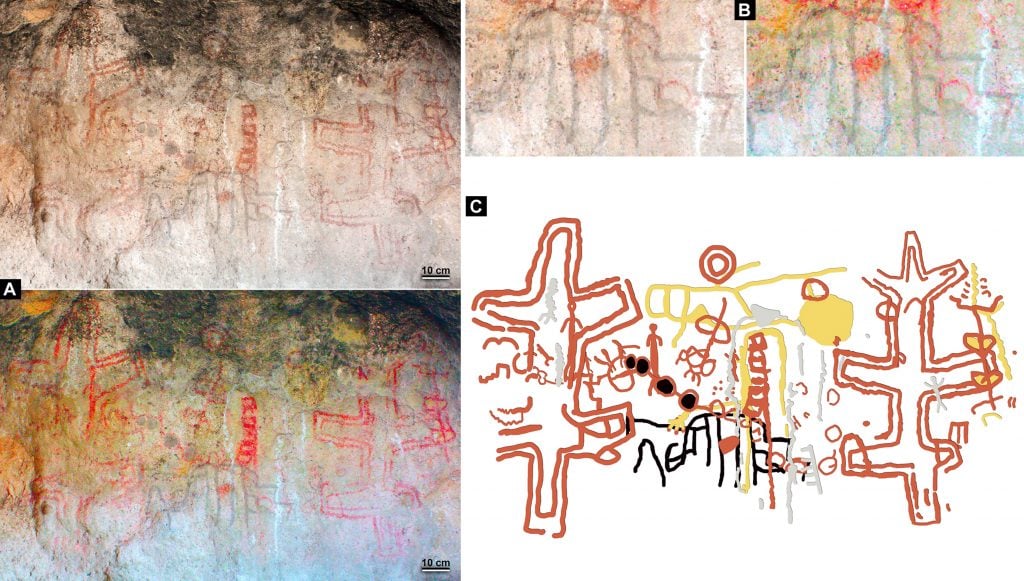

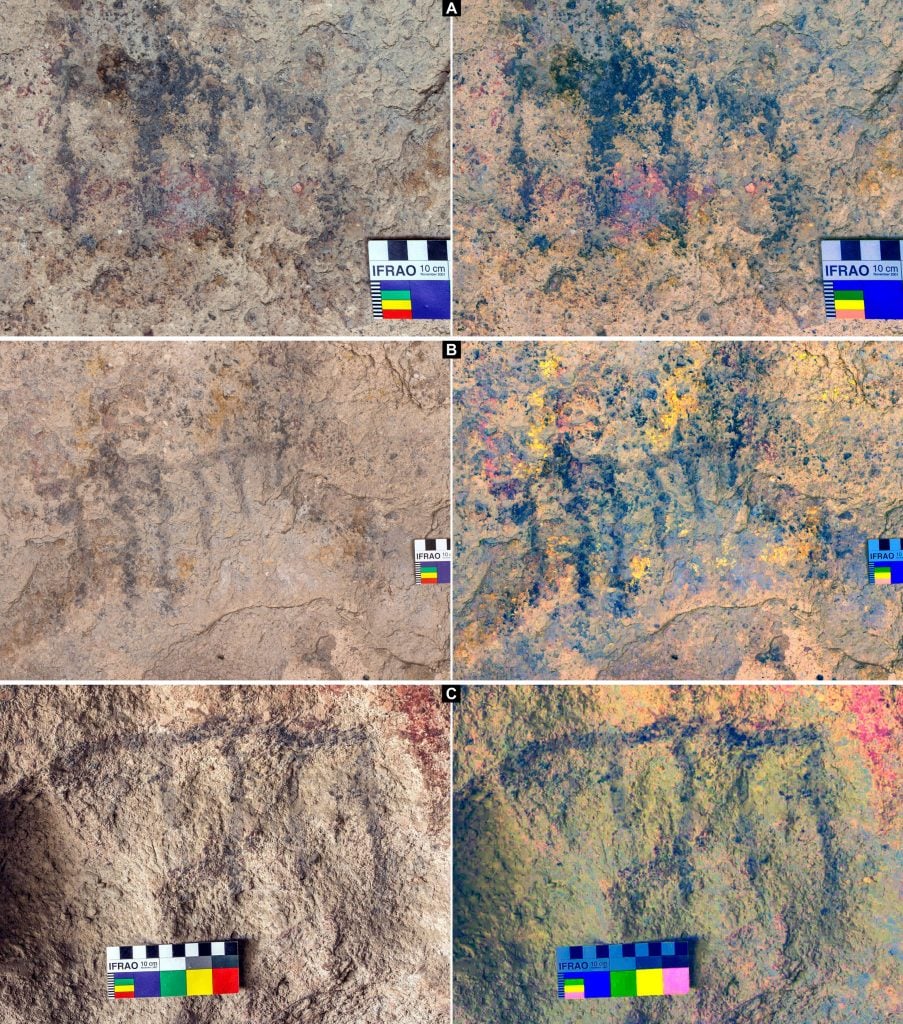

The walls of the cave site are covered in some 895 unique designs made from plant materials showing human bodies, abstract shapes, and animals such as rheas (a flightless bird also known as the South American Ostrich) and guanacos, a relative of the llama. The artworks were added to the cave walls by more than a hundred generations of people living in the region, and new research has pinpointed the earliest contributions. Cueva Huenul 1 isn’t the only site for cave art in the region, but none have been found to contain such a “diversity in shapes and colours”, according to Guadalupe Romero Villanueva, the lead researcher in the new study.

Four abstract comb-shaped paintings were examined during the study. Radiocarbon dating was used to accurately date the drawings, made in red, white, yellow, and black pigments made from burned cacti or shrubs. The comb motif was drawn multiple times across the cave by inhabitants of the site over the course of 3,000 years.

Image via Science Advances (2024). Image credit Guadalupe Romero Villanueva.

The exact purpose of the art in Cueva Huenul 1 isn’t clear, but one theory is that the drawings were made to pass information across more than 100 generations of people living in the notoriously dry and extremely hot area. Co-author of the study, Ramiro Barberena told Live Science that “we think it was part of a human strategy to build social networks across dispersed groups, which contributed to making these societies more resilient against a very challenging ecology […] there were large parts of the landscape without water, but in order to survive as hunter-gatherers, they would have needed to stay connected […] it would’ve been hard to make it on your own, so an exchanging of information was important”.

Patagonia was one of the last places on Earth to be chosen by humans as a settlement, with the earliest settlers believed to have arrived in the Argentinian region around 12,000 years ago. In comparison to Jebel Irhoud in Morocco—believed to be the earliest human settlement on Earth, with Homo sapien fossil remains found there aged more than 300,000 years—Patagonia is remarkably new.

Romero Villanueva described the discovery as “a shock”, and that it’s been moving for their team to think about the people who created this ancient art: “they were at the same place, admiring the same landscape; the people living here, maybe families, were gathering here for social aspects. It’s really emotional for us.”