People

‘I Go as Far as Beauty Will Take Me’: Patti Smith on Making Genre-Bending Art Through Loss, Motherhood, and Crisis

Smith and Soundwalk Collective's exhibition "Evidence" is on view at the Centre Pompidou.

Smith and Soundwalk Collective's exhibition "Evidence" is on view at the Centre Pompidou.

Nadine Khalil

Patti Smith bears a commanding presence. Dressed in a t-shirt, black vest, and faded jeans when I met her at the Centre Pompidou in Paris earlier this fall, she carries a rebellious air, tempered with age. She is still a fierce performer, her incantations conveying both lyricism and rage.

On- and off-stage, the New York-based artist exudes wisdom that comes from being part of several worlds: punk rock, performance, and poetry—which was her starting point—but also visual art. Although mostly known for her music, Smith has been recognized for her writing, winning a National Book Award for Just Kids, a memoir of her relationship with the artist Robert Mapplethorpe. Smith is lesser known as an artist, though it stems from the core of her creative work. Currently, she is showing her drawings and paintings—where her writing is often intermingled—in the exhibition “Evidence” (on view until March 6, 2023) at the Centre Pompidou, Paris.

“Evidence” is anchored in a decade-long collaboration between Smith and the Berlin- and New York-based artist duo Soundwalk Collective, which consists of French-born multidisciplinary artist Stephan Crasneanscki and Italian sound artist Simone Merli. For their trilogy of albums, The Peyote Dance, Mummer Love and Peradam (2019–2021), Smith vocalized the poems of Antonin Artaud, Arthur Rimbaud, and René Daumal, which play as a non-linear narrative on headphones alongside the duo’s ambient field recordings from Ethiopia, Mexico, and India—places that greatly marked the lives of these respective poets. There are ephemera and landscape-inspired drawings Crasneanscki brought back from his journeys following the poets’ footsteps, as well as Smith’s hand-drawn evocations of Artaud, Rimbaud, and Daumal. For their part, Soundwalk Collective’s audio materializes places influential to the poets, such as the rustle of trees by a Sufi shrine in Harar where Rimbaud followed the Sufist trail in the 1880s.

In this textured work, it is Smith’s gravelly voice—the result of a chronic bronchial condition—that leads. She demonstrates an astounding range of linguistic registers between recitation and improvisations. At a live reading with Soundwalk in late October after the exhibition opening, Smith became a hallucinatory Artaud and channeled Rimbaud at his deathbed, transporting the listener to the edges of mortality. Her powerful oration took on the magnitude of Daumal’s metaphysical quest through his unfinished novel, Mount Analogue. Mid-way through the performance, she recites Mummer Love, her own poem to Rimbaud, in which she chants: “I long to hear that which I have made, and then outlive it,” a powerful manifesto on the timeless resonance of art

I sat with Smith for more than an hour, speaking about everything from war and motherhood to climate change and her artistic process. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

“Evidence” at Centre Pompidou. Photo: Bertrand Prévost

You’ve been associated with the 1970s punk movement, Best-inspired poetry, rock music, photography, writing and spoken word. Does Patti Smith have many lives?

I’ve had many second chapters in my life, often propelled by loss. I had a rock-and-roll band and I left public life in 1979. I married the love of my life and then he died 16 years later. I returned to public life sometime after that. As a human being, I’m relatively simple. I’m very work-oriented, I’m not extremely social. I have my friends that I love. I don’t like entering a lot of social situations. I’m not the most generous person—I might be generous as an artist, but if I’m at a dinner party or something, I mostly want to leave. I don’t like making small talk. I’m not very curious about people, which is perhaps not the best way to be, but I have so much responsibility. I have children and I’m always in work mode. I’ve always been like that. As a teenager, my imagination was always moving.

Is that to do with the way you were brought up?

My father was a deep humanist. He liked his solitude, but he cared about people. He fought the Japanese in World War II and was heartbroken that America dropped two bombs on Japan. He never really got over that. He quoted [poet] Robert Burns all the time: “man’s inhumanity to man.” He was a beautiful person and my mother was very open, loving. She didn’t care what your sexual persuasion, religion, or race was. If you came through our kitchen door, all she cared about is that you were kind.

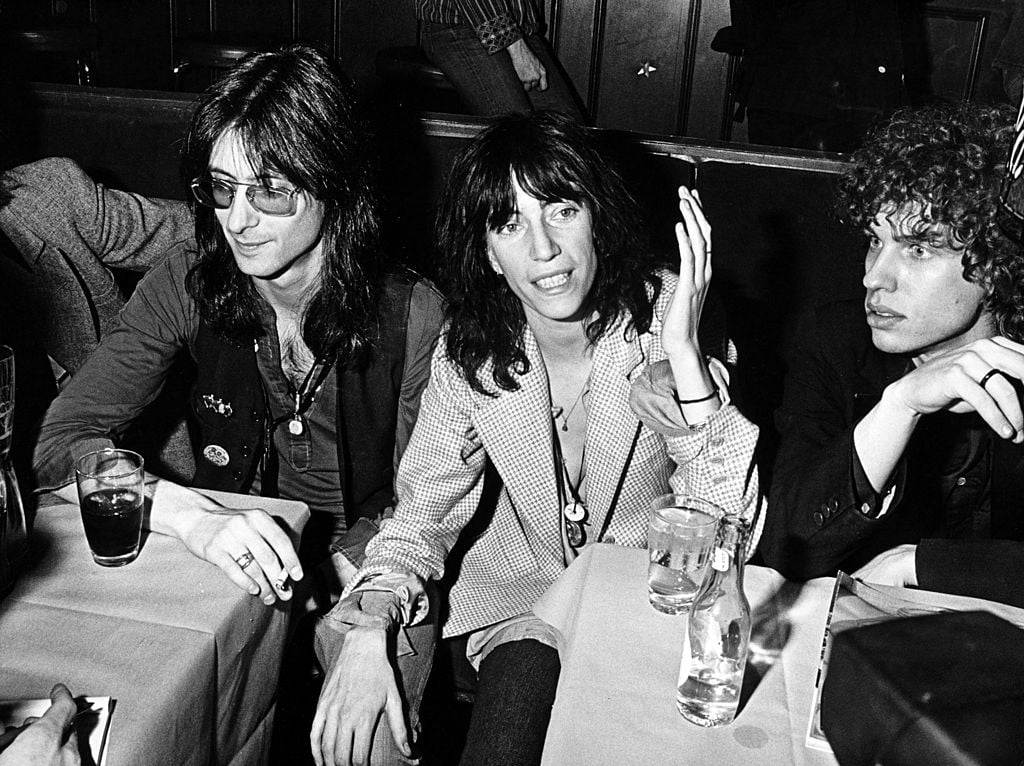

Patti Smith and Stephan Crasneanscki in Soundwalk Collective’s studio in NYC. Photo: Satya Crasneanscki

Walking through the exhibition on view at Centre Pompidou, I was struck by the ways in which you awakened these historical poems by Antonin Artaud, Arthur Rimbaud, and René Daumal—like when you cite Daumal’s last poem to his wife, for example: “I am dead because I have no desire…seeing that we are nothing we desire to become…into a blind darkness go, those dedicated to a non-knowing.” Your tonality takes on such a powerful mix of acceptance and defiance that you take the listener back to the moment in which he gives into imminent death.

Thank you. Part of an important duty of presenting the text is to try and enter it. Often, I’m repeating it or evolving and seeing where it will take us, so I’m a sort of vessel for the text. I don’t try to understand the text necessarily, or break it down, like taking the philosophical work of Wittgenstein and trying to comprehend every line. I try to bypass scrutiny and imagine Daumal, and feel what he was feeling. Daumal was dying when he wrote Vera. He knew he was dying and he wanted to leave his wife something. He left her, in this little poem, everything and nothing.

What brought you to French literature?

I discovered Rimbaud when I was 16, and then [Paul] Verlaine, [Gerard de] Nerval. I read [Albert] Camus, [Jean] Genet, and [Marguerite] Duras. I understood and felt their language. It called to me. It’s just something about the French voice that speaks to me. I like the mind; sensual writing doesn’t attract me. All three writers [that Soundwalk Collective and I] worked with have such expansive minds, and took me to places I’ve never been. It’s a country of the mind.

“Evidence” at Centre Pompidou. Photo: Bertrand Prévost

You’ve mentioned that this idea of looking back at someone who is gone and what they’ve done for the world—be it a musician like Jimi Hendrix or a writer like William Burroughs—is about creating a space that lives on. How do you channel life and death in your work?

I’m not a very analytical person, so I might channel these things in the middle of writing something humorous. Part of my work is to remember the dead, walk with them, and keep them alive in my work. It could be my husband, Sam Shepard, or my mother. It could be the Van Eyck brothers creating the Ghent Altarpiece. Wherever I tend to journey, I enter into their world, but I don’t do it selflessly. I’m always enriched in this kind of work.

So it’s not a kind of self-denial for you?

If it is, it’s not intentional. When you’re channeling other realms, some aspects of the self do dissolve, but you have to be careful with that… I’ve learned to pace myself and go as far as beauty will take me. There’s joyful excursions, and sometimes these golden moments where I feel I’m standing right next to Robert Mapplethorpe, where I can feel my brother’s hand on my shoulder. But those things you can’t ask for, they just happen. It’s like you go on a long walk in the forest and you don’t really know what will happen. And, all of a sudden, you chance upon a family of red deer in the sunlight, and it’s so beautiful. But you can’t go into a forest and say, “I’m going to find some deer and look at them.”

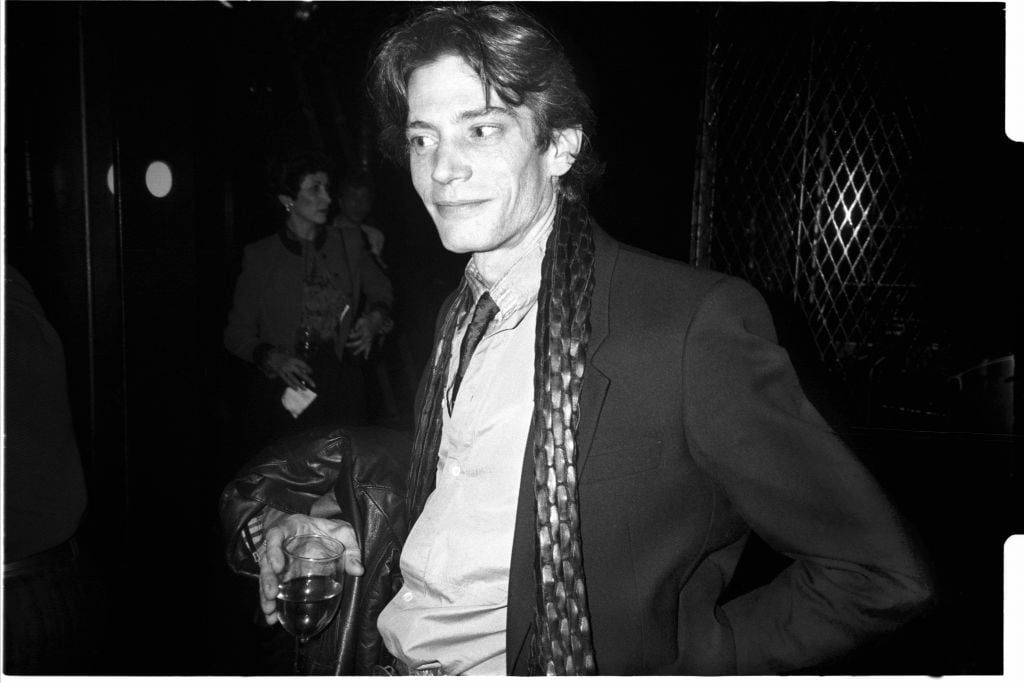

Robert Mapplethorpe in 1985. (Photo by Patrick McMullan/Getty Images)

Another short-lived artist’s journey marked your first collaboration with Soundwalk Collective in the album Killer Road. You and Stephan Crasneanscki happened to be seated next to each other on a plane headed to New York City, and Stephan was reading a poem by Nico from The Velvet Underground. Was it the text that drew you?

I knew Nico when I was young, I loved her records. When we were on the airplane, I saw that he was reading her poetry. Even though I knew her, I didn’t know that she wrote poems. Stephan thought of a very interesting way to deliver her poems [for our first album]. As she was dying during her terrible [bicycle] accident in Ibiza, there were millions of crickets, the sound of crickets screaming in the night. She was in this ravine alive and all she could hear was this sound. Stephan recorded the crickets and wanted to use that as a basis for this exploration into her consciousness at the end of her life. That is what drew me; I knew I could bring another level in reading [her texts] and hopefully achieve what he was looking for, a journey into a journeying consciousness. I like to do work that challenges me or gives me the opportunity to create something of worth or something no one has heard or seen before.

Is there an element of vicariousness to this impulse of embodying another person’s life or creative practice?

Well, it’s not always a person, sometimes it’s an abstraction. I might start doing something by only getting a sense of the light at a particular moment, the atmosphere, or sound of the rain, and then I might feel like singing a little song, and it evolves. You have to think about the whole picture.

For instance, I was violently opposed to America going into Iraq. And when they invaded Iraq, on the first day of spring, I was heartbroken and angry. We did a recording called Radio Baghdad, which is basically a field of churning rock chords. I didn’t know what it was going to be. I didn’t have any lyrics or anything, but what I was sensing, being a mother, was how would I feel being a mother on this on the first day of spring, hearing the planes coming, knowing bombs are going to be dropped. I’ve never been to Baghdad and I don’t know any women from Baghdad, but I am unified with all mothers. So, I just found the mother in me, transported to the situation in Baghdad, where American planes were dropping bombs on my home. I spoke to my children and then cried out to them. This is another way Stephan and I work together.

Patti Smith (Photo by Jorgen Angel/Redferns)

How does the creative process between you two unfold?

Sometimes, Stephan will give me a track—like the one of heavy rains in Ethiopia that’s in the exhibition. For that one, I improvised. I didn’t feel drawn to read [Rimbaud’s] poetry in response, but I was drawn to speak to him. I chose to do this poem called Mummer Love, which became the title of the album. It was written for him, it was almost like speaking to him.

What is it that pulled you to all these different registers of language?

Well, I love books. I have several different disciplines, but writing is my most important one. It is my daily practice. If I have to identify myself with one vocation, I would choose being a writer.

More so than a musician?

Absolutely, because I don’t think in terms of music. Of course, I’m a performer, but it’s not what drives me. My first album Horses is driven by poetry. The first words on it were from a poem I wrote when I was 20: “Jesus died for somebody’s sins.” Poetry is at the base of everything I do. Almost every drawing in the exhibition contains lines of writing. Because often, even my drawings start with a poem. The foundation for me is the word, and not necessarily the sound of the word because I write in silence.

“Evidence” at Centre Pompidou. Photo: Bertrand Prévost

What instilled your global awareness about environmental issues?

Being a mother. I remember when I was feeding my baby and watching the news. The actress Audrey Hepburn was in Somalia for UNICEF. There was a terrible famine there and she was trying to get people to be aware and help. She was standing with one mother, who was especially emaciated like a skeleton, so weak that she handed her baby to Audrey—this was all continuously on [the cable network] C-SPAN, so it wasn’t edited. Audrey looked down and the baby was dead. The woman didn’t even realize that her baby had starved to death. And I was sitting on the floor with my baby being fed. The empathy that I felt for that woman was almost unbearable. That is when I felt like I crossed another threshold. I’m not saying that you have to be a mother to feel that—if you look at Mother Teresa, every child was her child—I’m just saying that was my experience. And what can we do about this? Sometimes nothing.

Do you think that art has the power to catalyze change?

Art has the power to transform people, to excite and incite them, but only the people can make a change. Many of us were against the war in Vietnam, but we were still trying to unify in America. Then during the Nixon administration, the National Guard shot and killed four students in Kent University in Ohio, who were just hippies protesting. They didn’t have guns. Neil Young wrote the song Ohio that played on the radio everywhere. Between what happened and the song that articulated what happened, it ignited the people to march. It was so undeniable that the government had to end the Vietnam War. If Neil Young had written the song, and nobody did anything, it would have been a good thing to have articulated this tragedy. But because the people responded to it, and got out on the streets in the hundreds of thousands, that’s when change happened. Like what’s happening in Iran right now. You could write a song or a poem, but who is putting their life on the line? The people.

What’s the greatest fight now?

Climate change, but at the moment, it’s also the threat of a madman pressing a button— whether we are worried about Trump or Putin or whoever, we can’t have nuclear war. Not only would it destroy whatever it would hit, but also radiation for a lifetime of illness and the devastation of the environment. Even two years ago, I would have said climate change is number one. But now we have this at number two, right under it.

“Evidence” is on view at the Centre Pompidou until March 6, 2023.