People

‘A 21st-Century Andrew Carnegie’? How the Late Paul Allen’s Unorthodox Taste Made Him One of the Top Art Collectors in the World

The billionaire philanthropist and collector never stopped learning.

The billionaire philanthropist and collector never stopped learning.

Eileen Kinsella

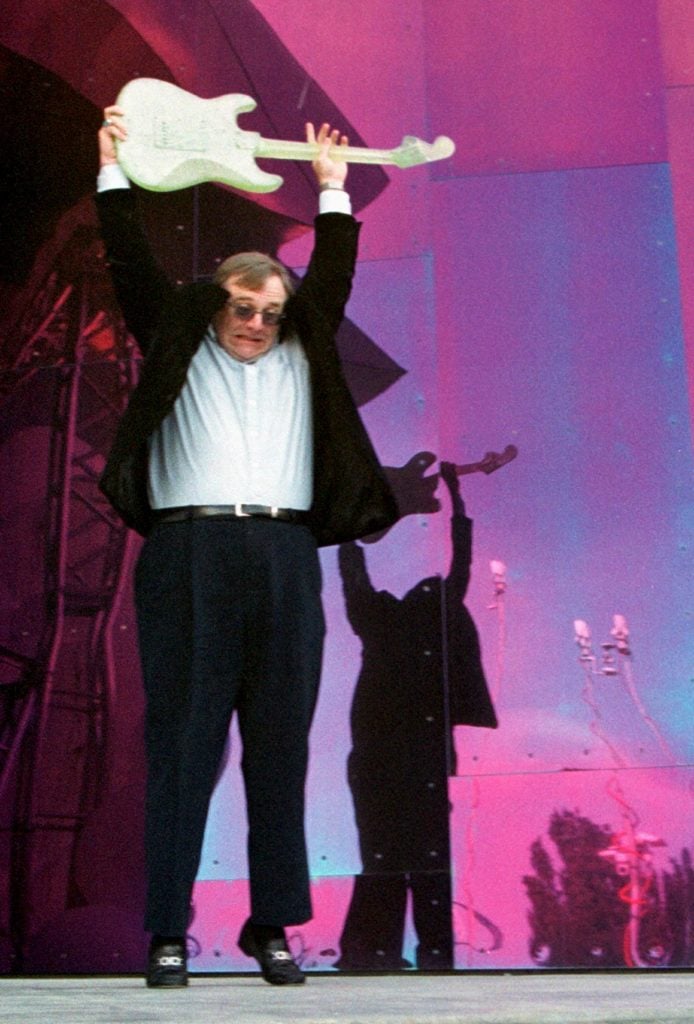

After decades of high-profile philanthropy and patronage, the late billionaire Paul Allen gave the public its first real glimpse into his impressive art collection back in 2006, when the Experience Music Project (now the Museum of Pop Culture, or MoPOP) in Seattle organized “DoubleTake: From Monet to Lichtenstein.”

The show, the first major exhibition to feature his collection, included 28 paintings. Curated by Impressionism expert Paul Hayes Tucker, it showcased some unlikely pairings—Claude Monet next to Jasper Johns and Renoir side by side with Roy Lichtenstein—and was intended to use a “compare-and-contrast” method of highlighting art-historical similarities across centuries.

If there was grumbling at the time about “odd pairings” or whether or not a music museum was the best venue for a show of fine art masterpieces, the unorthodox display nonetheless made clear how serious the Microsoft cofounder was about collecting—and how he approached it. At the time of Allen’s death last week at age 65 from Hodgkin’s lymphoma, the collection was reportedly worth in excess of $1 billion.

Jan Brueghel the Younger, The Five Senses: Sight (ca. 1625). Image: Paul G. Allen Family Collection.

“What differentiates Paul from other top collectors is that he didn’t have any need to justify his collecting to anybody,” Ben Heywood, executive director and chief curator at the Bellevue Arts Museum in Washington, tells artnet News. Heywood was formerly director of Allen’s short-lived Pivot Art + Culture in Seattle. “[Allen] was not collecting as part of a peer activity where the collections were assembled in order to make him look good,” Heywood says.

“He would ask questions and listen, and would remember everything,” says Pablo Schugurensky, who worked closely with Allen as an adviser in his role as director of art collections for Vulcan, the holding company Allen created in 1986. Schugurensky, who is now a private adviser, worked with Allen from 1998 to 2005. “He was ambitious about collecting and he was always extremely curious about learning,” Schugurensky says.

In 1998, the advisor was helping oversee a competition for art selections at the Seahawks’ football stadium, the team Allen purchased in 1996. At the time, Allen already had many major artworks. “Contemporary art was something he didn’t have a background in at the time, but he enjoyed it,” Schugurensky adds.

Gustav Klimt, Birch Forest (1903). Paul G. Allen Family Collection.

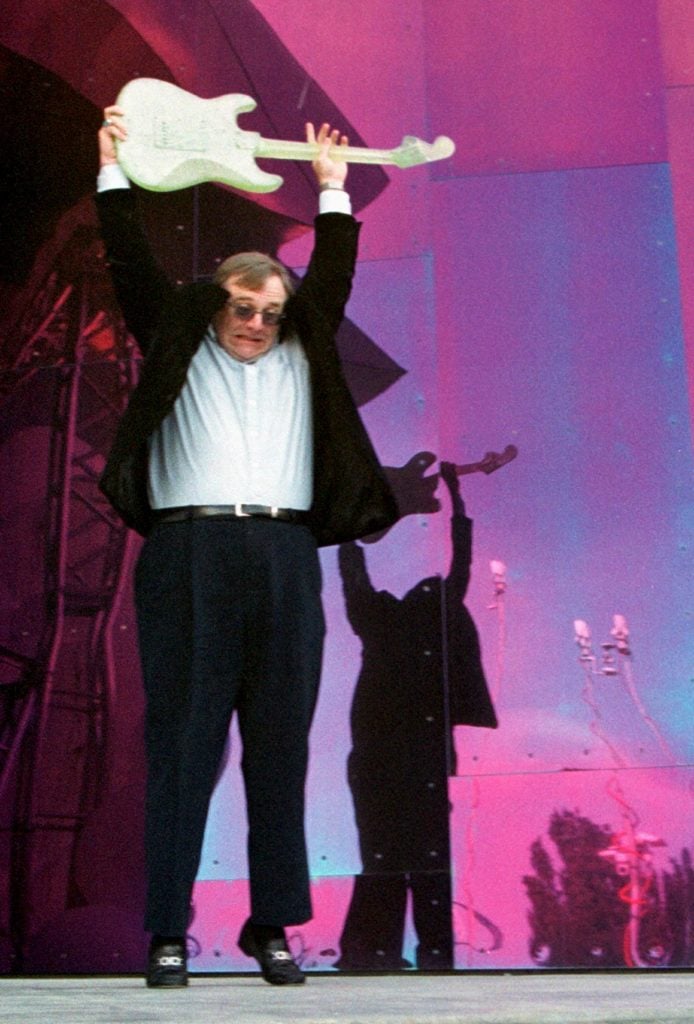

The curiosity paid off. By 2015, the billionaire’s collection was appearing in venerable art institutions around the country. That year, the Paul G. Allen Family Collection worked with the Seattle Art Museum and the Portland Art Museum to organize “Seeing Nature,” a major traveling show of 39 important European and American landscape paintings from Allen’s collection that spanned 400 years of art history. The landscapes, arranged chronologically, reflected the breadth of his collecting, ranging from pieces by Jan Brueghel the Younger, Canaletto, Manet, Monet, and Turner to more contemporary works by David Hockney, Gerhard Richter, and Ed Ruscha.

After a stint in Portland, the show traveled to Phillips Collection, the Minneapolis Art Institute, the New Orleans Museum of Art. Appropriately enough, the final stop was in Seattle.

“He had so many interests, but he was passionate as an art collector and very engaged in all his pursuits along with business pursuits,” Kimerly Rorschach, director and CEO of the Seattle Art Museum, tells artnet News. Rorschach describes Allen as a generous supporter of the museum over many years and says his contribution to the museum’s Olympic Sculpture Park included a land purchase that was made at “a critical time in our history.”

J.M.W. Turner, Depositing of John Bellini’s Three Pictures in La Chiesa Redentore, Venice (1841). Paul G. Allen Family Collection.

Allen himself said his earliest and “most impactful” experience with art occurred during a visit to the Tate Gallery in London as a young man where works by Monet and Turner left him “astonished.”

“I was first immediately taken with Impressionist and modern art,” Allen said in a video about the “Seeing Nature” show. “But as time goes by, you start to understand the history of the progression of art and how art evolved, and your tastes and your eye develop over that period of time.”

According to Schugurensky, that passion was accompanied by careful research and education, even as Allen’s collection was expanding substantially. “He was very aware visually. He collected because he was really interested in art and understood the importance of the works he was acquiring,” Schugurensky says.

Part of the advisor’s job was to bring information to Allen—about works he already wanted, as well as about works Schugurensky thought might interest the billionaire. He shared details about appropriate pricing, condition, caretaking, and storage “in order to protect his interests,” the advisor says.

While Allen often said he did not purchase art for investment, he certainly made some savvy moves. In late 2016, he consigned Gerhard Richter’s Düsenjager (1963) to Phillips, with an asking price of about $35 million. According to the artnet Price Database, the painting had previously sold at auction at Christie’s New York for $11.2 million. Sources confirmed to artnet News that Allen was the buyer. The painting went on to sell for $25.6 million, considerably less than expected but still a tidy profit and a hefty $14.4 million price jump in a span of about a decade.

Gerhard Richter Düsenjäger (1963). Courtesy of Phillips.

At the most recent edition of Art Basel in Hong Kong, power dealer Lévy Gorvy brought Willem de Kooning, Untitled XII (1975), an important abstract work that had the added luster of being consigned by Allen. The gallery had discussed offering it privately but the decision to hang it in their booth turned out to be a smart one: It was snapped up on the first day of the fair, with an asking price of about $35 million.

The Paul G. Allen Family Foundation was established in 1988 by Paul and his sister Jody. Under its arts and culture arm, the foundation extends philanthropic support to local community art initiatives. In a letter posted on the foundation’s main website, Jody Allen writes: “As a family, we believe in taking chances on creative thinking, supporting the unusual approaches and unproven ideas.”

The foundation’s initiatives include a hip-hop residency that partners with Seattle’s Museum of Pop Culture, Arts Corps, and the SODO Track, a public art project that gives 40 artists two miles worth of wall space to create murals for an “urban art gallery.”

Willem de Kooning, Untitled XII (1975). Courtesy Lévy Gorvy

Outside of his collection, the Seattle Art Fair,which is run by Vulcan, may be Allen’s art-world chef-d’oeuvre. Adam Glant, a member of the fair’s host committee and trustee at the Henry Art Gallery at the University of Washington, says Allen originated the fair by asking a simple question: “If Venice can have the biennale, why can’t something like this happen in Seattle?”

Allen and the Vulcan holding company became a key force behind the organization of the fair, which Glant says has become much more than just a regional event. “It’s both local and not local,” he says. “So many people attend it, and it has become such a high visibility event.”

“The Seattle Art Fair will certainly be a lasting legacy for him, regardless of how long the art fair prevails without him,” says Seattle dealer Greg Kucera. “It just wouldn’t have happened without his influence and encouragement. Any of us who were involved in the fair are completely respectful of him for that.”

SODO Track Mural Project in Seattle, WA featuring Broken Fingaz, Fingaz Magic Ink (2017). Produced by 4 Culture. WISEKNAVE

The art world at large is still asking whether younger generations of wealthy tech collectors will ever really get bitten by the art bug like Allen did. Heywood feels there is at least one distinction between Allen and his progeny. “You hear about how his passion for art had a lot do with his parents and his ability to travel,” she says. “I think one of his passions, as far as I understand it, is how do we get those people who basically work in the field that [he] invented from scratch to think about the importance of culture in its widest possible sense.”

Joseph Rosa, director of the Frye Museum, tells artnet News that it’s hard to overestimate Allen’s impact on the art world. “The Frye has been fortunate to benefit from this generosity in terms of exhibition support for a range of shows that reveal his willingness to take risks with us on new voices,” Rosa says. “I see Paul as sort of a 21st-century Andrew Carnegie, a business leader with a strong vision to connect his city to the arts and bigger creative dialogues. I think the full scale of his legacy will continue to be discovered through the indelible impact he has had.”

If the totality of Allen’s legacy is not yet clear, another billion-dollar question will also remain unanswered for now. Vulcan directors say they won’t address the fate of the late patron’s vast and valuable collection anytime soon.

“Paul thoughtfully addressed how the many institutions he founded and supported would continue after he was no longer able to lead them,” CEO Bill Hilf wrote in a statement emailed to artnet News. “This isn’t the time to deal in those specifics as we focus on Paul’s family. We will continue to work on furthering Paul’s mission and the projects he entrusted to us.”

—Additional reporting by Caroline Goldstein