Pop Culture

A New PBS Documentary Chronicles Edward and Jo Hopper’s Rich Yet Prickly Two-Artist Marriage

"HOPPER: An American Love Story" explores the vital role Jo Hopper played in her husband's career.

"HOPPER: An American Love Story" explores the vital role Jo Hopper played in her husband's career.

Adam Schrader

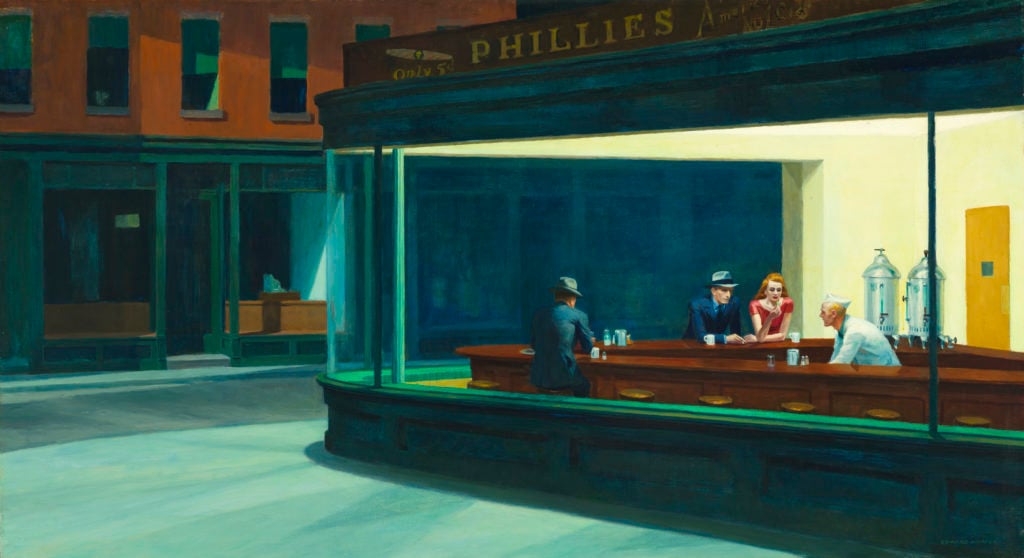

A new documentary about Edward Hopper, famous for paintings like Nighthawks (1942), focuses on his marriage to Josephine Nivison Hopper through her little-seen diary entries. The PBS film, HOPPER: An American Love Story, part of its “American Masters” series, is the latest significant effort to show how Hopper’s legacy was shaped by his wife, who forwent her own thriving career for the sake of her husband.

The documentary is a collaboration between producer Michael Cascio and former news anchor Cynthia Weber Cascio with the BAFTA-winning filmmaker Phil Grabsky. Hopper is voiced by Oscar-winning actor J.K. Simmons and Nivison Hopper is by Emmy Award-winner Christine Baransky. Alta Hilsdale, a love interest of Hopper, is voiced by Isabel May.

“Nobody’s ever done a full-scale biographical documentary about Hopper, even though he’s the rare artist who is popular commercially and critically at the same time,” Michael Cascio said in an interview.

“Obviously, you can look at Nighthawks and get some pleasure from it,” Grabsky said, noting that Nivison Hopper modeled for the famous painting. “But I think people can be very incurious, and the more you ask of the painting and the more you ask of the artist, the more you gain from the artwork.”

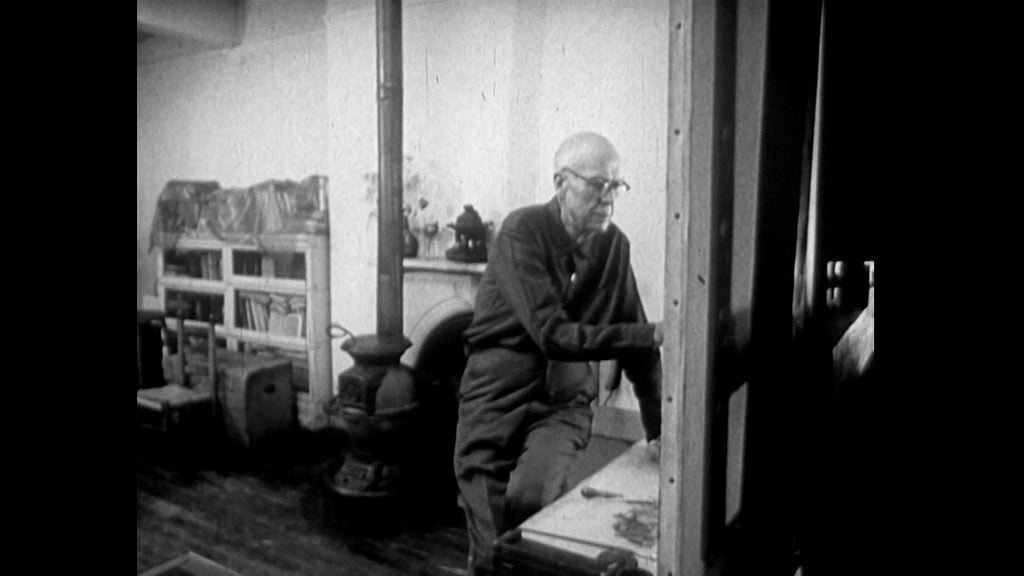

Post production of HOPPER: An American Love Story. Photo: EOS Hopper © Exhibition on Screen.

He said that the more one studies Hopper, the more they realize that he and his wife were a team. So, understanding her is crucial to understanding his work. Cascio said the filmmakers did find “nuggets” that had not been covered before from Nivison Hopper’s diaries, such as his secret 10-year affair and other biographical elements that are captured in his art.

“I think it’s clearly reflected in the work, the way his figures kind of turn away from each other and don’t look very happy,” Weber Cascio said. “That’s speculation, but there are a lot of such examples.”

Cascio said the team also came across interesting videos of Hopper later in his life. “He was sort of taciturn and didn’t give that many interviews… and that reveals a little about him. He’s sort of a curmudgeon but has a sense of humor,” he said.

Edward Hopper painting, 1964. Photo: Thirteen Productions LLC “The WNET Group.”

When Nivison Hopper met her husband, she was the more successful artist, Weber Cascio noted. Hopper hadn’t sold a painting in more than 10 years while she was showing her work next to the likes of Pablo Picasso and Man Ray. She advocated for him and got some of his work into a show at the Brooklyn Museum, which is when things took off for the artist.

“Jo was key in the role of Hopper, the artist we know today. If you have a gift and talent as Ed did but you don’t know what to do with it, what do you have?” Weber Cascio said. “Jo was his model, his muse, his marketer, and she was the one who got him to share his wonderful art with the world.”

But Nivison Hopper could be “frustrated” with her husband, and vented about him and what might have been about her own art career in her diaries. Weber Cascio called it “the kind of frustration a woman can feel sacrificing for a family,” adding that she seemed to get more and more frustrated as she aged.

Josephine Nivison painting, 1964. Photo: Thirteen Productions LLC “The WNET Group.”

There has been a renewed appreciation for Nivison Hopper and her own work in recent years, Weber Cascio said, adding that two of her works were featured in a recent exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. “If they held that exhibition five years earlier, they might not have been in there,” Weber Cascio said.

Cascio, when asked what Hopper might have been without his wife, theorized he likely would have remained an “unhappy illustrator,” pointing back to the fact Hopper hadn’t sold a painting in the decade before he met Nivison Hopper.

Hopper, however, seemingly never complimented his own wife, Weber Cascio said, and focused so severely on his career that it was “almost to the exclusion” of her. “I think it was a sign of selfishness that he could only open up if he thought people would be valuable to him,” Grabsky added. “He would accept her help in his art but from all accounts, and based on her diaries, he did not support her in her art.”

Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks, 1942. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Despite his flaws, Nivison Hopper is “always the woman in the picture,” Weber Cascio said. Grabsky added that the last image of the film is a photograph of the Hoppers sitting together on a bench after around 50 years of marriage, showing how their union is ultimately “a love story,” despite the difficulties they faced.

“Sometimes they’re pretty rough with each other,” he said. “But there are the two of them after 40 or 50 years of waking up every morning in the same bed, going to the cinema together, going to the theater together, all these things together.”

HOPPER: An American Love Story is available to stream on PBS.

More Trending Stories:

Art Dealers Christina and Emmanuel Di Donna on Their Special Holiday Rituals

Stefanie Heinze Paints Richly Ambiguous Worlds. Collectors Are Obsessed

Inspector Schachter Uncovers Allegations Regarding the Latest Art World Scandal—And It’s a Doozy

Archaeologists Call Foul on the Purported Discovery of a 27,000-Year-Old Pyramid

The Sprawling Legal Dispute Between Yves Bouvier and Dmitry Rybolovlev Is Finally Over