On View

How a Broadway Producer Recreated Peggy Guggenheim’s Groundbreaking ‘Exhibition of 31 Women’ on Its 80th Anniversary

The show returns to its original venue on 57th Street in New York.

The show returns to its original venue on 57th Street in New York.

Katie White

“I was a liberated woman long before there was a name for it,” art doyenne Peggy Guggenheim once remarked. Indeed, the trailblazing collector and socialite bucked the conventions of her time, living a bohemian lifestyle (including a brief and fiery marriage to Max Ernst), while championing women artists in an age when most female creatives were sidelined to roles of wife and muse.

This week, New York art-lovers will have the rare and fleeting chance to see the work of the women artists Guggenheim heralded in the very 57th Street space that was once her Art of This Century Gallery. This time-traveling experience is the work of Tony Award-winning producer Jenna Segal who has revived Guggenheim’s pivotal “Exhibition of 31 Women”—the first-of-its-kind in 1943 to showcase only women artists—to mark its 80th anniversary. Segal’s show will run for a total of 31 hours, spread out over a week.

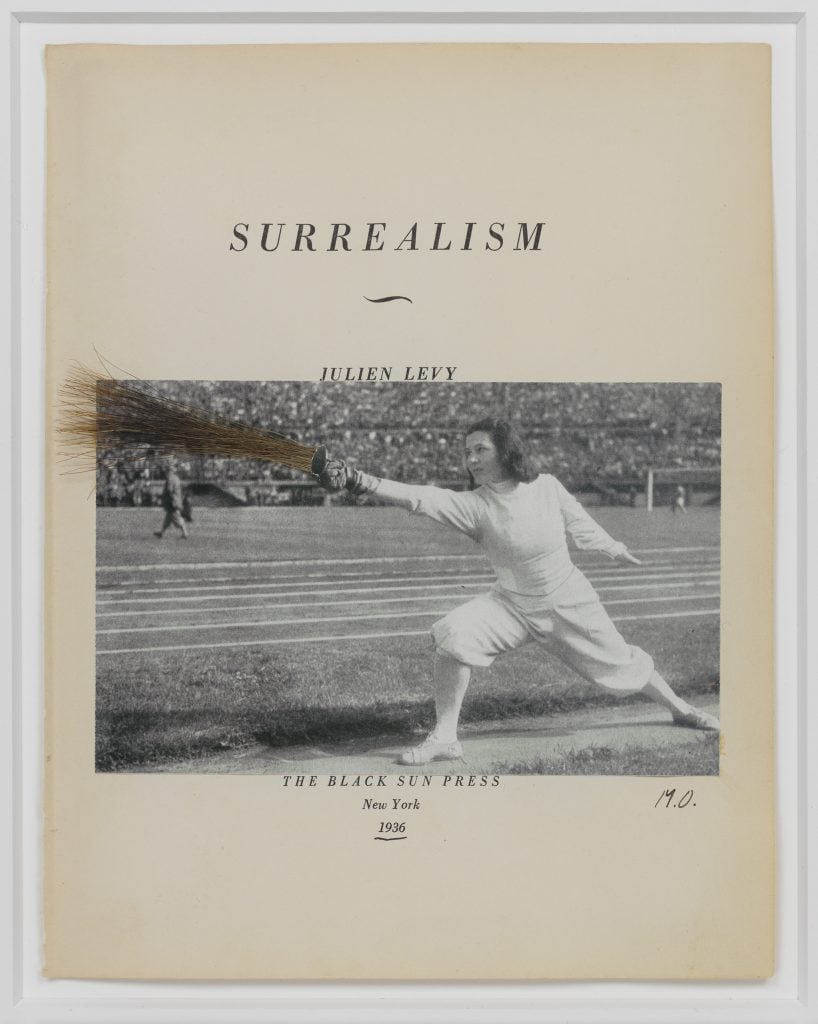

Meret Oppenheim, Untitled (1936). Photograph courtesy of the 31 Women Collection.

Guggenheim originally organized the exhibition at the suggestion of her dear friend Marcel Duchamp. The sweeping exhibition brought together works by today’s art-historical heroines including Frida Kahlo, Louise Nevelson, and Méret Oppenheim, as well as myriad others who have since fallen into obscurity such as the hauntingly poetic French artist Valentine Hugo and Swiss-born American abstract artist Sonja Sekula.

The works on view are all from Segal’s personal collection and represent a larger passion project for the producer, who has long admired Guggenheim’s ethos.

Berenice Abbott, Peggy Guggenheim (1926). Collection of Jenna Segal.

Segal—who is the founder of Segal NYC, a production company focused on highlighting women creatives—first became interested in the famed art world patron when she visited the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice while backpacking through Europe in college. Captivated by the collector’s vision, Segal then devoured Guggenheim’s fascinating autobiography and learned of her heroic efforts to protect artists in Europe at the dawn of World War II.

“I bought her autobiography and read it on the train as we were continuing to travel and it really struck me that here was this American woman who I had never been taught about [and who] had done so much,” she said. A seed of inspiration had been planted. “I tucked her in my heart,” Segal explained of her affection for Guggenheim, knowing, on some level, she would return to her story later.

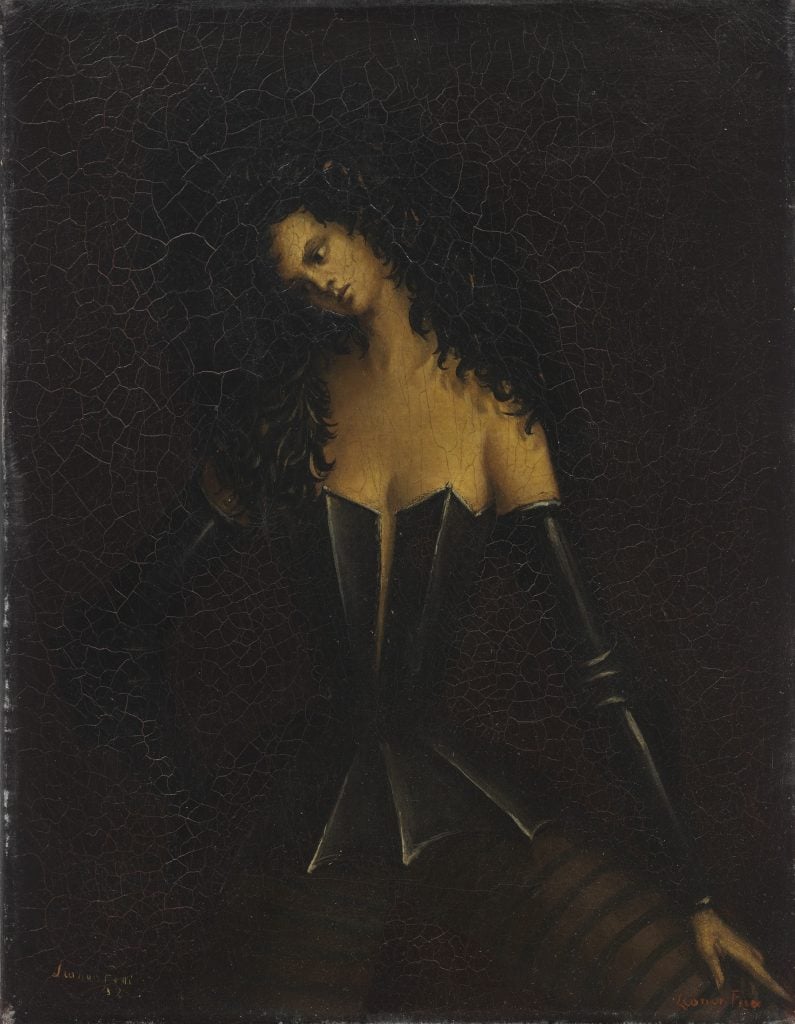

Leonor Fini, Femme En Armure I (Woman in Armor I) (1938) Photograph courtesy of the 31 Women Collection.

Then, in 2020, deep in quarantine, Segal happened to return to Guggenheim’s autobiography. She’d long considered “31 Women” a pivotal, and tragically unknown, moment in women’s history. With the itch to produce, Segal’s thoughts coalesced around the possibility of bringing together the works of all the artists included in the exhibition in one place.

“At first I just wanted to see if I could find all these women,” Segal noted. Since no known photographs of “31 Women” exist and many works included were listed simply as “untitled,” Segal decided she would try to feature at least one work by each of the 31 artists, rather than try to recreate the exact show itself.

She soon immersed herself in a crash course on art history and collecting, taking to online auction houses, eBay, and dozens of other sources to assemble her collection. She decided she would focus on works made as close to the exhibition date as possible. “Through self-education, I began to see the differences in what these artists were making in the ’30s and ’40s and what they were doing in the ’50s and ’60s.” Amid a moment of global uncertainty, she found these earlier works resonated with her.

Valentine Hugo, Portrait d’Arthur Rimbaud (1936). Collection of Jenna Segal.

This immersion was an eye-opening experience filled with rich stories that touched Segal personally: “I could go on and on about any of these artists.”

In the friendship between Leonora Carrington and Leonor Fini, two artists included in the collection, for example, she found a corollary. Having met in Paris in 1938, the two began a long-lasting and intimate correspondence in exile from their homelands. Their exchanges ranged from deeply felt memories to artistic considerations. “It reminds me of an email correspondence I have with a friend of mine, a woman writer in London,” Segal noted.

One artist, French painter Valentine Hugo, Segal finds herself acquiring again and again. “Valentine Hugo haunts me, I say” Segal laughed.

“As I was building this collection, I painted one wall in my office with magnetic paint so I could move around images of works by these artists to see it all in one space,” she explained. “I left one day and I come in and somehow in the night, the Hugo image had moved up to the ceiling. She was reminding me of her.” For Segal, the uncanny experience speaks to the mysteries artists are able to both capture and evoke.

If Hugo has haunted Segal, another artist has eluded her: Gypsy Rose Lee. Gypsy Rose Lee was an iconic 20th-century American burlesque entertainer who was also an artist and playwright. While Segal has managed to acquire works by all other 30 women, she remains on the hunt for a work by Lee.

Unknown Photographer, Gypsy Rose Lee with artwork likely to be the one included in the original “Exhibition of 31 Women” in 1943. Photograph printed from original 35 mm negative. Photo: The 31 Women Collection.

“She was the Kim Kardashian of her time,” enthused Segal. “It’s shocking that people don’t know her today and that I can’t find a single work by her. It’s like if in 80 years, there were not a pair of Skims to be found!”

Today, Segal’s office is in what was once Guggenheim’s famed 57th Street gallery. Asked how this came about, Segal laughed. “I went to the door and knocked,” she said, noting a producer’s instinct. “I figured I’d just go see for myself.” After some cajoling, Segal secured the space, which had fallen into drab disrepair. Segal enlisted oopsa creative studio and agency, led by architects Eric Moed and Penelope Phylactopoulos, to invigorate the space with aspects of the gallery’s original design by Austrian American architect Frederick Kiesler.

While Segal is happy the exhibition is garnering attention, she hopes it will be a call to historians and a springboard for the future.

“I am not a historian. I am not a museum. I don’t claim to be an expert,” she said. “Peggy said, ‘I listened and I became my own expert,’ and that’s what I would say I am. But in the annals of art history, there are people who know a lot more than me. I hope they’ll come in and feel as inspired as I do and we’ll get some great scholarship.”

“The 31 Women Collection” is on view at 30 W 57th St, New York through May 21. Reservations for free, timed-entry admission can be made here.