Photo: Eikoh Hosoe. Courtesy of the artist, Akio Nagasawa Gallery | Publishing (Tokyo) and Jean-Kenta Gauthier (Paris)© The artist.

Romain Mader, Ekaterina: Bientôt (2012).

Photo:© Romain Mader / ECAL.

Tate Modern’s major exhibition “Performing for the Camera,” a fascinating and carefully researched survey that explores the intense relationship between photography and performance, opens today in London. And—I’m sure you’ll be glad to know—it’s not at all an exhibition about selfies (although they do make an appearance in the form of Amalia Ulman’s conceptual Instagram persona).

Organized by Tate’s senior curator of photography Simon Baker, the show gathers a whopping 500 works spanning 150 years, which tackle various questions to do with (self)representation, shifting identities, and—why not—posing.

Seen from our social media-obsessed vantage point, these are all topics that one is tempted to describe as “timely.” But what Baker illuminates through this show is that they are in fact as old as the photographic medium itself, regardless of new technological developments. Photography, Baker claims, has always been performative, ever since it was first invented circa 1839.

Yves Klein, Saut dans le Vide (1960).

Photo: Courtesy of Centre Pompidou – Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Fonds Shunk-Kender. Gift of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation in memory of Harry Shunk and János Kender © Yves Klein, ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2016 / Collaboration Harry Shunk and Janos Kender © J.Paul Getty Trust. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

The show’s brief is, thus, daunting and its scope, ambitious. Conveniently, though, the first room provides visitors with the key to approaching the exhibition, its kernel boiled down to three works. Yves Klein’s Leap into the Void (1960) and its preparatory images; Aaron Siskind’s Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation (1956-65); and Charles Ray’s Plank Piece I-II (1973). These foreground the show’s three main conceptual avenues: the collaboration between artists/performers and photographers (Klein with cult photographic duo Shunk-Kender), the creative documentation of a performance (Siskind), and the conflation of performance and photography into sculptural form (Ray).

Despite this seemingly didactic approach, Baker has managed to combine curatorial rigor with familiarity and excitement in the gallery rooms. Lesser-known archival images, for example documentation from performances from the 2nd Gutai Exhibition (1956-7) or Eleanor Antin’s Adventures of a Nurse (1975), meet well-known artworks, such as Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills (1982) or David Wojnarowicz’s Arthur Rimbaud in New York (1978-9).

Works by Hannah Wilke, Joseph Beuys and VALIE EXPORT at “Performing for the Camera” at Tate Modern.

Photo: Courtesy of Tate Photography © Joe Humphrys, Tate Photography.

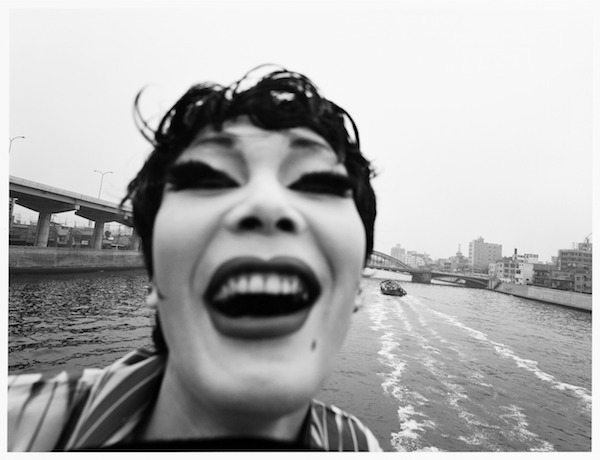

Likewise, a room about artists’ use of posters, fliers, and ads from the likes of Andy Warhol, Joseph Beuys, Hannah Wilke, and VALIE EXPORT, complements a bright-red display devoted to a more obscure gem: A Private Landscape (1971), the collaborative project of photographer Eikoh Hosoe and actor Simon Yotsuya, a soaring exercise in gender-bending pantomime carried out on the streets of Tokyo and captured with beauty and precision.

If it all seems a little scattered, it’s because it is. One of the main successes of the exhibition, in fact, is the eschewing of the traditional chronological hang in favour of a conceptual one. Taxonomical hangs in large group shows appear to be legion these days—a lasting hangover, perhaps, from the so-called archival turn. They also tend to make for pretty dry itineraries. But at Tate, Baker and his collaborators have devised a structure that manages to benefit the artworks, even shed light on new aspects, rather than restrict or hinder them, as is very often the case.

Eikoh Hosoe, Simon: A Private Landscape (1971).

Photo: Eikoh Hosoe. Courtesy of the artist, Akio Nagasawa Gallery | Publishing (Tokyo) and Jean-Kenta Gauthier (Paris) © The artist.

The seven conceptual categories begin with “Documenting Performance,” which features photographs by Babette Mangolte of Yvonne Rainer’s and Trisha Brown’s dance pieces. Or Harry Shunk and János Kender’s documentations of countless iconic performances, including works by Klein, Niki de Saint-Phalle, Yayoi Kusama, Antin, and Merce Cunningham.

What this first, more historical part of the exhibition does, among other things, is shed light on these unsung heroes of performance documentation. Baker’s point, and I couldn’t agree more, is that the images created by Shunk-Kender and Mangolte transcend their archival function. With their sophistication and intention, they become artworks in their own right.

Francesca Woodman, Untitled (1980).

Photo: Courtesy of the Wilson Centre for Photography © Estate of Francesca Woodman (New York, USA).

Halfway trough the show, a suite dedicated to Francesca Woodman will surely be a crowd-pleaser, as the appreciation of Woodman’s stunning explorations of bodies moving through—and becoming—space never ceases to grow. The prints of Woodman’s medium-format photographs, small and square, draw the viewer in beguilingly. Up close, the artist’s cunning interplay of textures of human bodies and props transcends the flatness of the medium. Her photographs become condensed sculptures.

The exhibition is unflinching in its serious approach, which—given the rise of prosumer image-making and the ensuing deluge of mediocre “performative imagery” (selfies, anyone?)—is certainly a relief. The show explores how artists use these technologies, and it never loses sight of this focus.

Amalia Ulman, Excellences & Perfections (Instagram Update, 8th July 2014),(#itsjustdifferent)(2015).

Photo: Courtesy the artist and Arcadia Missa.

But it does tackle the slippage of performativity in the terrain of real life, particularly in the exhibition’s final room. Alongside Ulman’s Excellences & Perfections (2014) and Romain Mader’s witty series Ekaterina (2012), one piece that stands out is Masahisa Fukase’s series From Window (1974), in which he photographed his wife each morning as she left the house to go to work. The high-angle shots record the plethora of moods the protagonist exhibits on each different morning: happy, resolute, cheeky, bored, tired.

It is a poignant example of our daily, unacknowledged performances. Because don’t we all, at times, “put on a brave face,” “cause a scene,” “make a fuss”? This is, in fact, one of the interesting questions that arise from the show: What is performing? How is it different from posing? And if isn’t, isn’t every single photograph depicting an aware human being an image of a performance?

Masahisa Fukase, From Window (1974).

Photo: Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery © Masahisa Fukase Archives.

As for a drawback, the only one I could find was the relentless two dimensionality of the show. Granted, “Performing for the Camera” is a photography exhibition, but considering the show’s keen accent on multidisciplinarity, the display of some physical remnants or props from any of the original performances, or perhaps the spatial reconstruction of some stage sets would have been a welcome interruption from looking at images hung on the gallery walls.

But that’s a minor complaint, for this show is a feast for the senses. It’s beautiful, thought-provoking, funny, and life affirming. If you like art that doesn’t get lost in the immaterial life of the mind, but that celebrates instead our living, breathing bodies, this exhibition is for you.

“Performing for the Camera” is on view at Tate Modern, London, from February 18 – June 12, 2016.