People

With Homemade Napalm and K-pop Anthems, Photographer-Filmmaker Diane Severin Nguyen Is Forging a New Genre of Image

See her paradoxical photographs and latest film in two shows, currently on view in New York.

See her paradoxical photographs and latest film in two shows, currently on view in New York.

Taylor Dafoe

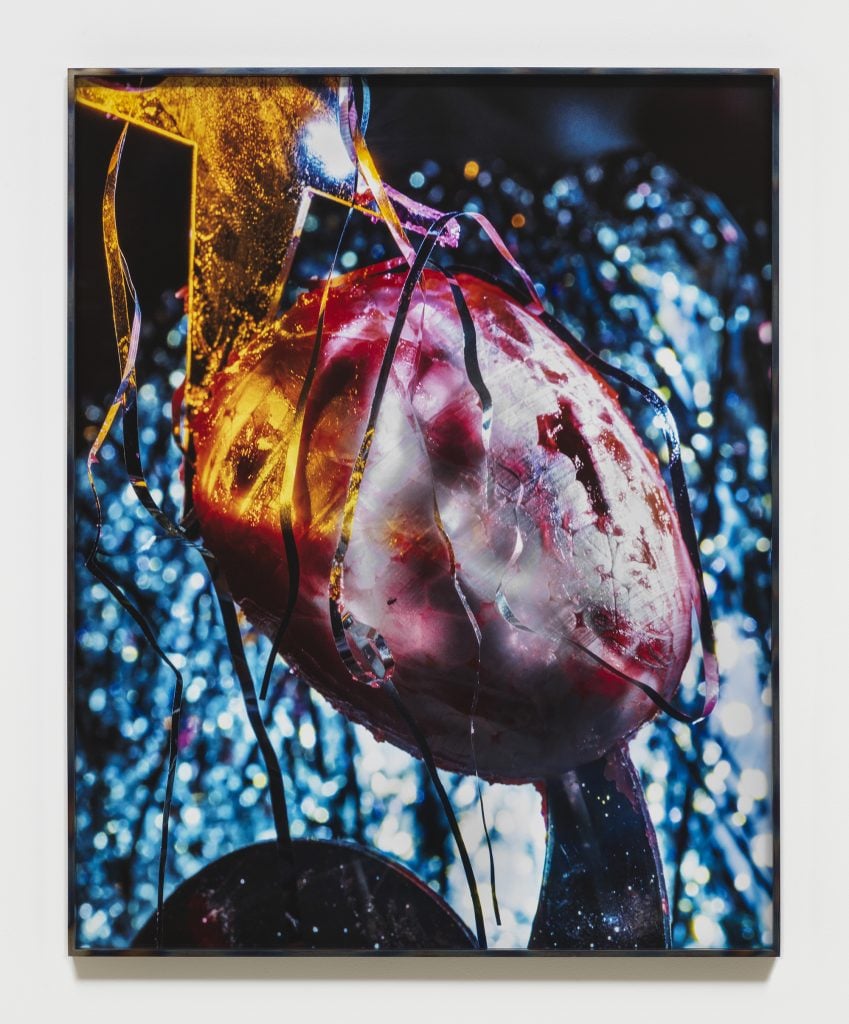

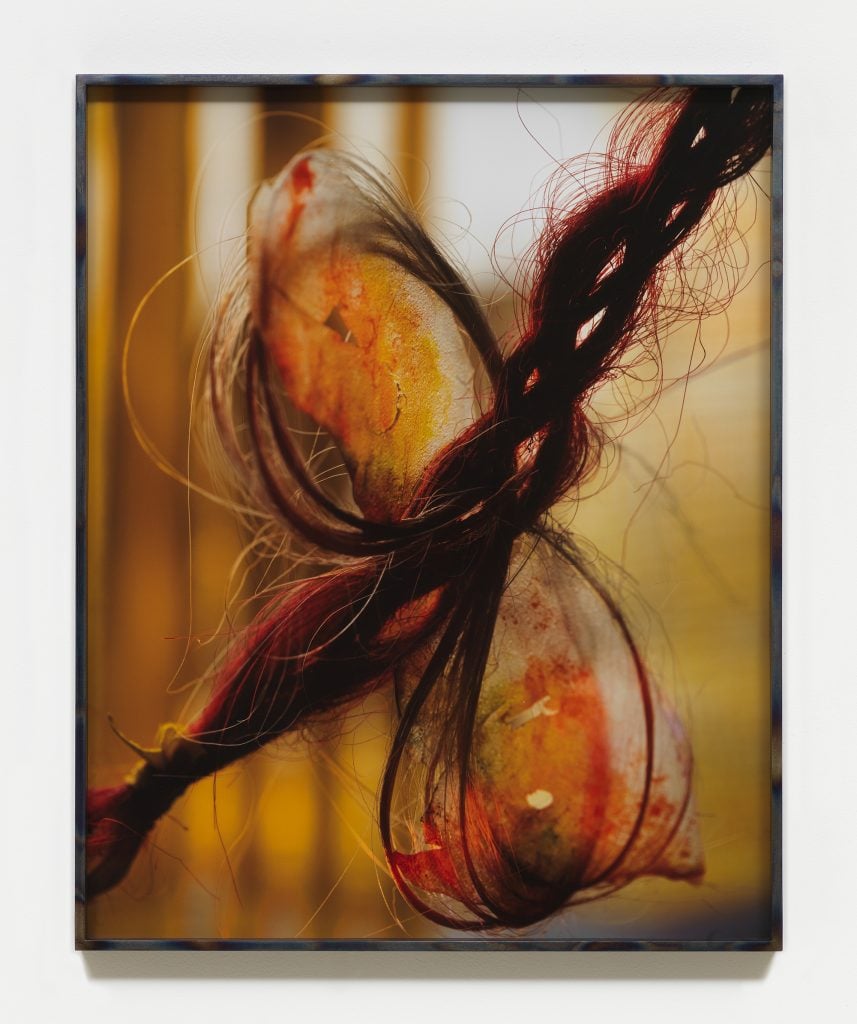

Diane Severin Nguyen doesn’t only make photographs, but when she does she becomes a kind of mad scientist. Before the lens she erects ad-hoc tableaux, Frankensteining together materials both natural and synthetic, exotic and quotidian—fish skin and ribbed plastic tubes, for instance; or latex gloves and toenail clippings. Often they are drenched in an innominate goo the color of Gatorade or activated through a kind of crude chemistry. Napalm is a favorite trick; she found the recipe on the internet.

And yet, even as I describe these materials, I’m not sure that’s what’s in the pictures. Through the artist’s manipulations of light, depth of field, and good, old-fashioned cropping, indexicality is stripped from the image, as is any documentary imperative. What we see seems familiar, but it doesn’t look it.

That’s the paradox at the core of Nguyen’s pictures, which occupy a nebulous space between the abstract and the representational. They leave you wanting for words, but try to find them and you’ll invariably fall short, locating the limits of language instead. At best you’re left with adjectives for how they feel: dank, disgusting, delicious, sick.

Diane Severin Nguyen, Kill This Love (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Bureau, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Before I met Nguyen at SculptureCenter in New York, where her first solo institutional exhibition, “IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS,” is on view through December 13, I wondered if she, too, would grasp at descriptors. She had plenty to say.

“It doesn’t matter what it ‘is’ that’s being photographed. My compositions emphasize a moment in time…[Everything] is in perpetual motion. Nothing is stable,” the 30-year-old artist said, sitting cross-legged atop a bench in the center’s courtyard, sounds of the exhibition’s titular film echoing from inside. Of the photographs (many of which are on view just down the road in MoMA PS1’s “Greater New York” exhibition), she explained, “It’s a doubling effect: creating a moment of transformation and also using materials for their aura, rather than their function or symbol.”

Nguyen talks more like an academic than an artist, flitting between references to art theory, philosophy, and pop culture—often in the same sentence—stopping only for the occasional puff on an e-cig. She’s a novel thinker: to her, music is photographic and photography is liquid; she talks of the objects in her still images as she would close friends, and the actors of her films as props. It can be a challenge to keep up.

The artist herself is clear on her aesthetic aim, however. “I think it’s all just an attempt to work against this Cartesian mind-body split, where we want to see better and see more and to categorize,” she said, noting how “that perspectival advantage [can be] weaponized, even when it’s about sympathy or ‘empowerment.’”

Diane Severin Nguyen at work filming IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS (2021). Courtesy of the artist.

Nguyen is hesitant to share many details about her background and personal life. The daughter of Vietnamese refugees, she was born in 1990 in Carson, California, a southern suburb of Los Angeles. Her parents spoke little English; she grew up largely “deprived of Western media and music,” an upbringing that surely contributed to her skepticism of such cultural forces later on.

She didn’t pick up art until after finishing undergrad at Virginia Commonwealth University, a political science degree in hand, and moving back to LA around 2014. She was in her mid-20s then and working a series of “random jobs.”

Into Nguyen’s world came photography, a discipline that drew her interest “because it gave me more immediate access to expressing an idea.” Initially driven by a desire to deconstruct the image, to expose its artifice, she soon realized she remained invested in its potential. “I found it to be an interesting contradiction, how art always made photography into this false thing—an illusion or something,” she said. “I understood that, but at the same time I never stopped feeling that images have the potential to be extremely moving and powerful and spiritual.”

Diane Severin Nguyen, As if it’s your last (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Bureau, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

In 2018, she entered graduate school at Bard College, where she began to make the photographs described above. She was thinking about coloniality, communism, and the camera’s role in reinforcing structures of power throughout the 20th century: “In my mind, I’m always theorizing about how images correspond with different economic and political systems.”

Illustrating this, she proffered a historical anecdote. In communist North Vietnam in the 1960s, photographers smuggled in low-grade cameras from abroad, often with just a handful of film rolls at a time. With so few frames to work with, they pushed for perfection, carefully staging photographs before putting finger to shutter. The pictures were propagandistic—labor was glorified, women wielded guns—but also technically sophisticated, not unlike commercial photography. They were a far cry from the other images we know from this era, taken by photojournalists documenting the war. Those pictures were more naturalistic, but no less driven by political ideology, she pointed out.

Nguyen came to identify the latter photographs as contrivances of American capitalism. “With documentary images, it’s about taking as much as you want and choosing narrative later,” she explained. “There’s an editing process that’s possible with material wealth and access.”

If these two approaches, the documentary and the staged, exist as poles on an axis, then her own images might lay smack dab in the muddy middle. “For me,” she went on, “it’s about combining these two spaces…and revealing how they uphold one another.”

Installation view, “Diane Severin Nguyen: IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS,” SculptureCenter, New York, 2021. Photo: Charles Benton.

For her Bard thesis, Nguyen moved into digital video, and with it has begun incorporating familiar people, recognizable places, and plot—elements her still images pointedly resist. “My photographs’ affective melodrama comes both from the desire and also the failure to represent everything that surrounds them,” she noted. “My filmmaking approach loosely narrativizes this process. It dissects the symbolic regimes which the photographs are formed under, but maybe refuse to speak directly to.”

That’s especially true of her latest film, IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS (2021), the focal point of her exhibition at SculptureCenter. It’s projected onto a screen that sits on a stage, framed by silk curtains and surrounded by a scarlet-colored carpet that evokes both a movie premiere and the Soviet flag. It follows a young Vietnamese girl named Veronika who, after washing up on a faraway shore, makes her way to modern-day Poland, cold and concrete, with vestiges of the Cold War on every corner. There she joins a budding K-pop group (the genre is big in the Eastern Bloc, it turns out), whose members haze the newcomer through bizarre rituals.

In the end, the protagonist finds identity through assimilation at the same time as she finds liberation through dance. So does the film itself, in a sense: what starts out as an impenetrable art piece (a solemn piano etude plays as voiceovers recite musings on revolution by leftist thinkers like Hanna Arendt and Ulrike Meinhof) finds a more accessible frequency halfway through when it morphs into a what is essentially a K-pop music video, set to a song that sounds like candy but reads, lyrically, more like a Marxist manifesto. “Facing the future with a hot blood and a red heart / Let’s join the workers and the peasants and march,” Veronika sings.

Diane Severin Nguyen, IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Bureau, New York.

While Nguyen’s photographs hook the viewer by burrowing into a slippery space between recognizable genres, the film gets there by embracing the conventions of melodrama and movie-making—and relying on the charisma of its talented actors and dancers to do some of the legwork along the way. It’s a move that represents a significant evolution in the artist’s own practice: while her still photographs freeze moments of inchoate instability, with the film, she presses play again, allowing her subjects to operate in that liminal realm.

“The characters in the film almost create scenarios or compositions that at times convey very intricate scenarios that she creates in the photographs,” said SculptureCenter curator Sohrab Mohebbi, who commissioned the work.

Recalling conversations with Nguyen during the production of IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS, Mohebbi points to a recurring question that’s also at the center of the final product. “One question that I asked her while she was working on the film was, ‘Diane, is this a form of propaganda?’ I don’t think it is, but it’s interesting to think about how you would create an image at this point that is not ideological, but still revolutionary.”

I didn’t pose this question to Nguyen, but the song at the end of her film offers one possible answer: “If revolution is a sickness,” Veronika belts in the bridge, “I wanna be sick, sick, sick!”