Gallery Network

Photographer Michael von Hassel Trains His Lens on the Unseen Side of Football

As the Euros kick off in Germany, the artist speaks about the surreal experience of documenting empty stadiums.

As the Euros kick off in Germany, the artist speaks about the surreal experience of documenting empty stadiums.

Sophie Neuendorf

As the 2024 UEFA European Football Championship kicks off in Germany, renowned photographer Michael von Hassel is tackling a new project exploring the unknown aspects of the beloved sport. Von Hassel’s stomping grounds are usually on the fringes of society, trekking to war-torn countries, or exploring nature in its most remote and untouched state. From North Korea to Iraq, he’s documented areas of the world that remain both unreachable and unimaginable to most.

Now, he’s debuting a very different kind of exhibition: images of Germany’s most important football stadiums, as they’re empty and await the adoring throngs of fans. Amid the excitement of the Euros this month, von Hassell trains his lens on a global phenomenon.

“Your work must be allowed to be controversial and we all need to meet before this work and engage in discussion” von Hassel says. “Art must also be allowed to be wrong, and through conversation we can create a better tomorrow.”

Michael von Hassel, Olympiastadion E Berlin, (2018). Courtesy of the artist and Anna Laudel Düsseldorf.

As the UEFA European Football Championship is about to start, you’re publishing a series of photographs around the subject. What does the sport mean to you?

Football is a world of its own and affects a large part of our society. It’s the favorite sport of many nations and a quasi-religion of millions of fans. I like to focus on the “other side” photographically. I try to show places that we all know, that we may have grown up in, that we visit weekend after weekend but in a completely different way; just like you’ve never seen your own football stadium before.

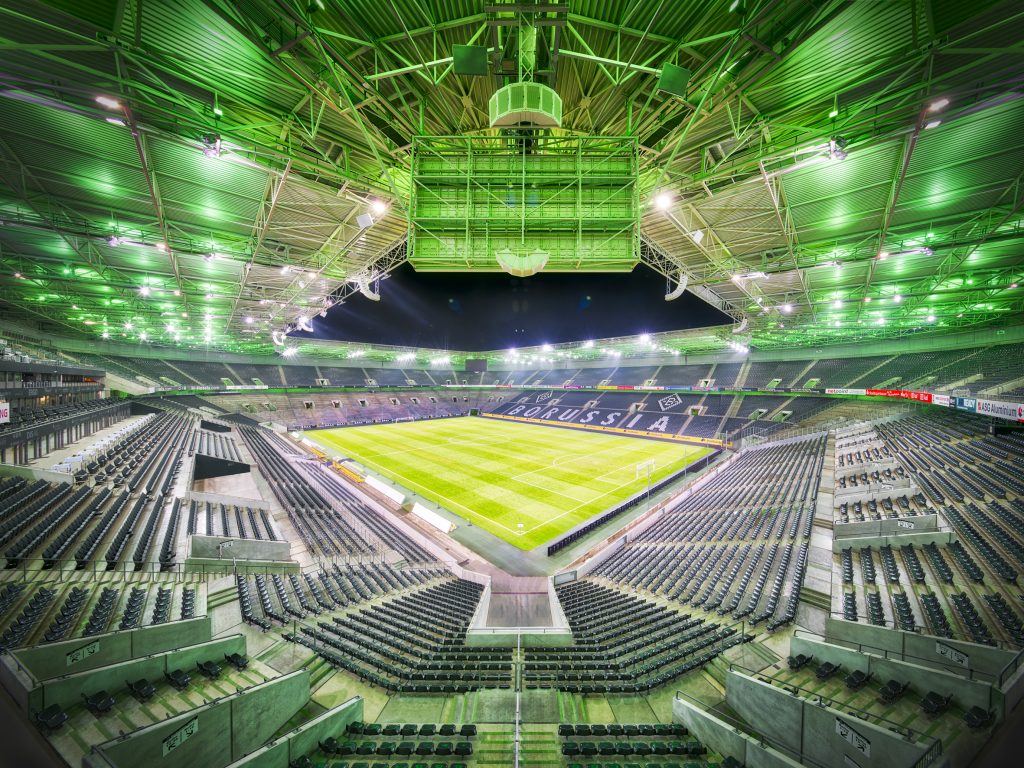

Michael von Hassel,

BORUSSIA-PARK D Mönchengladbach, (2018). Courtesy of the artist and Anna Laudel Düsseldorf.

After many photo series of this kind (e.g. the Munich Oktoberfest beer halls inside, at night, empty, fully illuminated), I wanted to get to know football entirely for myself. I wanted to take a look at our football country late at night when everyone is asleep. I’m not technically a football fan, I always keep a respectful distance and try to photographically portray our everyday lives. But I admire the gigantic achievements of the thousands of full-time and volunteer football employees and I wanted to create a photographic monument to this.

The images are centered around empty stadiums, which is unique. What are you trying to express with these empty vantage points?

I show the place as you can never normally experience it. This begins with the challenge that no one can simply call up FC Bayern Munich and get access to the unlocked, brightly lit stadium. So it’s extremely complicated to create this moment in my photo—if no one is in the stadium, the lights will of course not be turned on. There are also typically large lawn solariums on the playing fields, which provide the lawn with the light it needs to grow. In the end, the moment doesn’t actually exist in my photos and that’s what makes this series of pictures so special.

Now producing one of these pictures is difficult. But photographing all the country’s 37 most important stadiums like this is virtually impossible. But I did it. I also want to show these places in absolute perfection: the way they were designed and built. A full stadium with 80,000 visitors is visually pure— wonderful—chaos. But you can’t understand it anymore. It starts with the color of the seats. A collector of mine has season tickets for FC Bayern Munich. He saw my picture of the Allianz Arena in the gallery and actually asked me if the seats are really red. He has been sitting there for years and has no idea what color the seats are. I find that amazing.

Michael von Hassel, Allianz Arena B1 München, (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Anna Laudel Düsseldorf.

Finally and most importantly, I deal with mass phenomena and psychology of the masses. I want the viewers of the pictures to ask themselves to what extent they are immersed in a movement when they enter such arenas and whether they are simply adopting traditions, rituals, songs, behavior from the crowd or whether they are influencing this crowd themselves.

What does a place like this do to me and what do I do with it? The emptiness is intended to explain and show us how these monumental buildings function when they are full of people on many different aspects and levels.

Artists have, throughout history, depicted the zeitgeist. How do you feel soccer and the European Cup reflect todays society or humanity?

Football is a blessing and a bane at the same time. The ancient Romans called it Panem et Circenses (bread and circuses) and today it’s not much different. Football creates community, a herd, a gang, a sense of belonging. I can put on a team jersey and be part of a really big, loud, and supposedly strong family. However, I also adopt their traditions, rituals, customs or improprieties and— perhaps—deal with the most insignificant thing in the world.

Netherland fans are pictured during their Fan Walk at the official UEFA Fan Zone before the UEFA EURO 2024 Group D match between Poland and Netherlands in Hamburg, Germany. Photo by Selim Sudheimer – UEFA/UEFA via Getty Images.

Football is entertainment, nothing more and nothing less. But for so many people it is the absolute meaning of life. I’m happy for these people and I also think it’s terrible at the same time. Is it more important that a club just paid a hundred million Euros for a player, or that the war between Russia and Ukraine finally ends or doesn’t explode into a global conflagration? We distract ourselves from the things that really matter. But that helps many people to endure everyday life. I used to be a big critic of taxpayers sharing in the costs of football (infrastructure, the subway to the stadium, police operations, etc.). Today I believe that creates so much identity for many people who might otherwise be lost. It is therefore absolutely right that the general public contributes to the costs.

You’re renowned for traveling to areas of conflict and social-economic upheaval. What have these trips taught you about humanity and photographing in dangerous conditions?

If you go into the world with an open heart, are polite, respect local laws and customs, and politely say hello, thank you, and please, you will inevitably find that the world is a safe place almost everywhere. If you need help, you will be helped. People are friendly and good almost everywhere in the world, no matter who you are. Everyone wants peace, security, health, good food and that their children will one day be better off than they are. So you don’t need to be afraid, almost everywhere.

Artist Michael von Hassel stands in front of his studio. Photo: Felix Hörhager/dpa via Getty Images.

The picture that we get from history books and the media about an unknown country usually does not correspond to the truth that we find when we go there ourselves. It’s always worth taking your own picture on site. I literally create this: my own image. And even in countries like North Korea or Iraq, we will notice differences in many details from what we would have expected from that country or its people. The harder a journey is and the more dangerous it seems, the more you will grow in experience. Unfortunately, sometimes you have to go to the front of an active war.

The stories that I was able to experience on the Russian side of the front in Donbas show me a completely different “truth” of this conflict. Of course, I don’t adopt this view of things 100 percent. But I still have a lot to think about. Resolving any conflict involves listening to both sides. Ultimately there has to be a compromise. We seem to have forgotten that today. This actually applies to all conflicts of our time: Covid, Ukraine, climate change, inflation, medicine… Sometimes I fear that we are losing all of our civilizational achievements and are reverting to survival of the fittest.

Unfortunately, there are currently several war-torn regions worldwide, some closer to home. Will you be showing these through your lens as well?

I already do that again and again. Unfortunately, in the end, pictures of the battlefield near Donetsk or of destroyed Mosul in Iraq don’t sell as well as my pictures of the Oktoberfest tents. But I find another aspect astonishing. If I invite to a vernissage of a North Korea exhibition, almost 1,000 guests come. But when I show the photos of the demonstrations against the Covid policy, only 30 people come.

Photographer Michael von Hassel on site.

It seems to me that the further away a conflict or more of a mass psychosis is, the more the people around me are open to diverse perspectives. But if they are part of this mass hysteria (e.g. Covid), then our society loses all openness to a different opinion or even an image of it. An art gallery must always be a place where artists face the challenges of our time through their work. Your work must be allowed to be controversial and we all need to meet before this work and engage in discussion. Art must also be allowed to be wrong and through conversation we can create a better tomorrow.

If you could have dinner with any three photographers, living or dead, who would you chose?

Ansel Adams: I often stand on the roof of my car taking photos and think of him and his work. I would just love to wander through nature with him and absorb the beauty of our time.

Philippe Halsmann: I would love to know how he took the photo with Salvador Dalí, the cat and the curved waterfall.

James Nachtwey: I would like to know how one can endure so much pain after seeing so much truth of the world.

Sebastião Salgado: I admire the work of his wife and him. First the war photography, then Genesis and the big reforestation project. One of the really, really great ones! I’m just grateful that people like him exist.

Installation view, “Michael von Hassel: Cathedrals” at Anna Laudel Gallery.

Can you tell us about your upcoming exhibition?

I have just published the book “Bundesliga Cathedrals” at Callwey Publishing. The great Prof. Alexander Gutzmer is responsible for the text and many interviews with greats from German society: the artist Professor Markus Lüpertz, the world footballer Lothar Matthäus, the entertainer Joko Winterscheidt, and many more. Accompanying the book, I show the large-format images of all German football stadiums at the wonderful international Gallery Anna Laudel in Düsseldorf. Finally I’m excited to see how our very own football festival develops and which picture wins in the end.

“Michael von Hassel: Cathedrals” is on view through July 20, 2024 at Anna Laudel Gallery, Düsseldorf; Tuesday–Friday 12–6 p.m.; Saturday 11 a.m.–3 p.m. at Mühlenstraße 1, 40213 Düsseldorf.