People

How Did Collector Pierre Bergé Change the Art World? A Look at His Extraordinary Legacy

Bergé’s death came only weeks ahead of the culmination of museological projects that had been some 55 years in the planning.

Bergé’s death came only weeks ahead of the culmination of museological projects that had been some 55 years in the planning.

Hettie Judah

Outside of France, Pierre Bergé—who passed away earlier this month aged 86—was known largely as the business and sometime romantic partner of the fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent. Within his home country, however, his influence stretched well beyond the world of fashion, extending across both the cultural and political spheres. His personal enterprises extended to auction houses, theaters, magazines, and the dealing of rare books: Bergé even enjoyed a controversial tenure as president of the Opéra de Paris between 1988 and 94.

Bergé did not approach cultural matters merely as a businessman, but with a headlong, often irreverent, passion. In 1950, aged only 19, he became the editor and publisher of a left-wing magazine having encountered the writer Albert Camus during a night in jail after both were arrested at a political demonstration. Eight years later he met the 23-year-old Yves Saint Laurent, then head-designer for the house of Dior.

The two became lovers, and following Saint Laurent’s toxic dismissal from Dior, Bergé became manager and business partner in the young designer’s eponymous new house. Under the direction of Bergé, Yves Saint Laurent became a highly profitable business, and the pair adopted an extravagant lifestyle building up world-class collections of art, artifacts, and design.

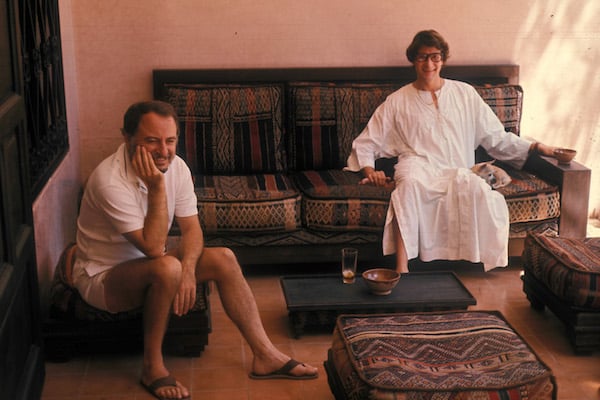

Yves Saint Laurent in Marrakech, 1977. Photo ©Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent, Paris/ Guy Marineau.

“Together, with Yves Saint Laurent, Bergé was a patron of so many cultural events: music, opera, exhibitions, literary prizes, architecture—their influence and support in these areas cannot be underestimated,” recalls François de Ricqlès, president of Christie’s, France. “Bergé was politically involved with François Mitterrand and valiantly defended the colors of our Republic—Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity—against all forms of exclusion, of racism, anti-Semitism and homophobia. Pierre Bergé also resolutely presented himself as homosexual; in his relationship with Yves Saint Laurent, he had anticipated what would become the law on marriage decades later.”

Bergé’s death came only weeks ahead of the culmination of museological projects that had been some 55 years in the planning. On 3 October, the Musée Yves Saint Laurent Paris will open in the former haute couture house at 5 Avenue Marceau, followed, on 19 October by the opening of Musée Yves Saint Laurent Marrakesh, in a purpose-built brick structure designed by Studio KO near the Jardins Majorelle.

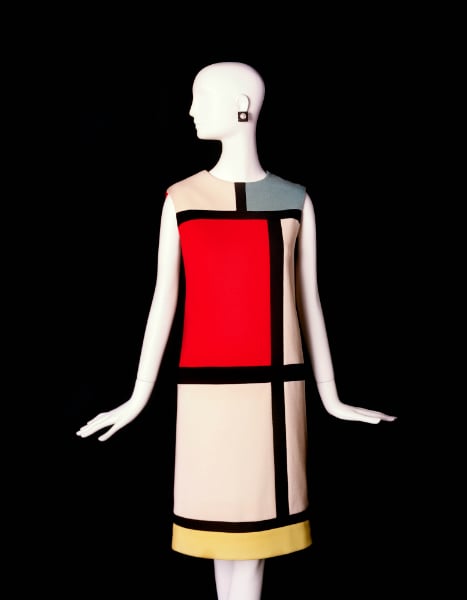

The creation of these two institutions was facilitated by an exceptional sale of 733 pieces from Bergé and Saint Laurent’s collection of art and design at Christie’s in 2009. Over three days and six auctions, the sale brought in $443.1 million, with highlights including paintings by Mondrian, a Brancusi sculpture, a Matisse still life, early work by De Chirico, and Art Deco furniture by Eileen Grey.

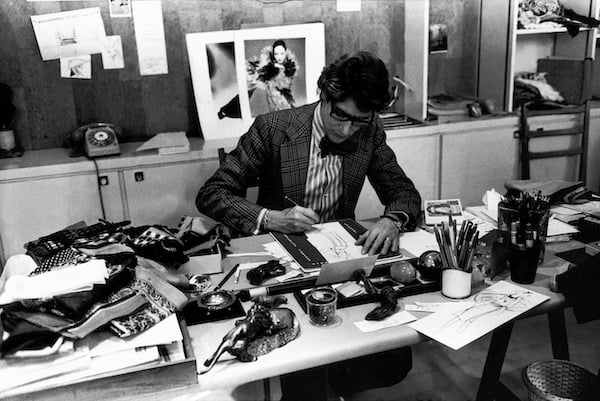

Yves Saint Laurent at his desk in 1976. Photo ©Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent, Paris/ Guy Marineau.

Speaking to the French newspaper Libération in 2012, de Ricqlès confided that it had been a long journey to convince Bergé to place the sale in the hands of an auction house connected to François Pinault: “Pierre Bergé abhorred the way in which François Pinault had bought the Yves Saint Laurent house without respecting the spirit of its creator.” De Ricqlès persevered, and when Bergé finally conceded, he made his motivation clear: “If I entrusted my sale to Christie’s, it is only for François de Ricqlès. He understood what I expected of him.”

In correspondence with artnet News earlier this week, de Ricqlès explained that he saw the sale as “a testament to the dedication and eye of the two collectors, one of whom, Yves Saint Laurent, was one the most influential fashion designers in the second half of the 20th century. The radical decision of Pierre Bergé to sell the whole collection, without keeping a single piece, brought to light a side of their lives that had not yet been fully understood and appreciated by the wider world—it was this dimension that fascinated the public.”

While some funds from the sale were put toward charities long supported by Bergé (notably AIDS research, a cause of which he has been a leading patron in France since 1988), 50 percent was funneled into the Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent. Founded by Bergé in 2002 at the closure of the Saint Laurent couture atelier, and dedicated to preserving the designer’s legacy, the Fondation is now responsible, among other things for the preservation and content of the two museums. Its archival holdings include more than 5,000 haute couture models with full matching accessories, over 1,000 photographic prints, comprehensive sketches and fabric swatches, notes and press cutting, all of which represent some six decades of planning and preservation.

Joanna Hashagen, curator of fashion and textiles at the Bowes Museum, which hosted the exhibition Style Is Eternal in collaboration with the Fondation in 2015, praises Bergé’s “great foresight. He and Yves had been disciplined from the start to keep all sketches, designs and catwalk garments. It is now the largest single archive of an haute couture designer, which Bergé was probably responsible for.” The Bowes Museum exhibition was one of a handful of carefully stage-managed shows held around the world over the last few years, as the Fondation’s archive has readied itself for mounting the rotating displays in its own museums.

Hashagen recalls the care and exactitude with which the exhibition was administered: “all the decisions that were made had to be ratified by Bergé. He strongly protects the legacy of Yves Saint Laurent,” she says. On the day of the opening “he toured it like a king with his royal entourage and we all waited nervously— his team and myself—for the reaction. He uttered the word ‘Magnifique!’ and we sighed with relief.”

Short cocktail dress a tribute to Mondrian. Photo ©Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent

This focus on details is familiar to the team running the Pierre Bergé & Associés auction house, which he founded in 2002 with salesrooms in Paris and Brussels. “The one thing which really mattered was for him quality, precision, and rigor: he always looked carefully at auction catalogues,” recalls auctioneer and vice president Antoine Godeau. “He was a close friend and always supported me during all those years. I remembered once at the beginning of the auction house we had a jewelry auction which didn’t go well in Geneva and he invited the whole team to dinner. He told us that failure was not important but we had only to think of the next one and make a success of it.”

Speaking to the New York Times in 2015, ahead of another fundraising auction (this, of his collection of art and artifacts from the Islamic world), Bergé outlined his aims for the two museums. They were to be cultural centers “that use Yves’s heritage and vision or true beauty to inspire new generations of talent. New artists must be able to come and learn from these sites. I want our legacy to be one that centers around sharing and providing, creating forums of possibility.”

The Paris museum will focus on Saint Laurent’s couture work, both with Dior and his own house, as well as his prêt-a-porter collections for Rive Gauche. Displays will change frequently so as to safeguard the fragile textiles from over-exposure.

Long evening ensemble inspired by Picasso

Photo ©Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent

In Marrakesh, a city that Saint Laurent and Bergé had visited regularly since 1966, and to which both felt a special attachment, the museum functions as something closer to a cultural center. Beside exhibitions dedicated to Saint Laurent’s work, there is also a gallery equipped to host visiting exhibitions and an auditorium for film projections, high-definition live broadcasts from L’Opéra de Paris, recitals, conferences, and colloquiums. The opening exhibitions will include a show of paintings by Jacques Majorelle, an artist whose former gardens and studios were both re-opened as museums by Bergé, one as an environmentally sustainable garden project, the other as a museum of Berber culture.

“Mr Bergé was a man who transformed memories into projects throughout his life,” says Olivier Flaviano, director of the Musée Yves Saint Laurent in Paris. “The two museums which are to open this autumn are his last such efforts, and possibly the most important. Speaking personally, I have been profoundly shaped by his discerning taste for the arts. He has been my school.”

With state-of-the-art facilities hidden deep within the Marrakesh site, the legacy of Yves Saint Laurent, and his influence on future generations of designers is assured. Bergé however, was outspoken about changes within the fashion industry in the years since Saint Laurent’s death in 2008.

Portrait of Yves Saint Laurent (1986). Photo Guy Marineau ©Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent

“The time of Chanel, Balenciaga, Dior and, of course, Yves—well, that time is over,” he told The New York Times in 2015. “So too is the era of haute couture. Completely over, gone. This is why what we call luxe today is just ridiculous. To me, that whole industry now—all money and marketing—it is all something like a lie.” More than the end of an era, he saw something closer to the death of the very art form he had striven so hard to elevate to the status of a museum exhibit.