Reviews

An Uncanny Exhibition Turns the Online World Into Artistic Material

The dark corners of the web inspired a group exhibition that became the site of political action.

The dark corners of the web inspired a group exhibition that became the site of political action.

Kate Brown

Something I’ve noticed: Almost a decade on, the Berlin art scene is still haunted by its 2016 biennale. The DIS-curated show enters the room whenever “post-internet art” is referenced, or during any discussion about the state of culture in the 2010s, and it rattles the picture frames when one of its artists has an exhibition here. It haunts the art scene because there is still no settled consensus on whether it was good or not. “These artists seem to want to have their fun and still get credit for topicality, but let’s get real: I have seen spambots with greater sensitivity,” wrote critic Jason Farago in the Guardian at that time. “Try being sincere; try believing in something,” he cautioned before taking himself to the opera.

So when the group show “Poetic Encryptions” opened in February with a handful of the same artists as the DIS exhibition—with post-internet art among the leitmotifs on view at KW Institute of Contemporary Art, which was one of the Berlin biennale host venues—it was inevitable that people would draw comparisons with the earlier exhibition. Yet, in spite of a few crossovers (Jon Rafman, Simon Denny, Trevor Paglen), the state of play feels different. That abject irony that embodied this art scene around the 2016 Berlin Biennale, so cozied up it was with corporate slang and a flip of the hair, seems to have bled out—a feeling of real stakes has emerged.

Installation view of the exhibition Poetics of Encryption at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2024; Photo: Frank Sperling

Spread across four floors, “Poetics of Encryption,” which runs through the end of May, is part of an ongoing project by KW’s curator for the digital sphere, Nadim Samman, that looks at how virtual life has been shaped by and is shaping climate collapse, artificial intelligence, online micro-ideologies, and Pepe the Frog. It casts a wide net, prodding some unwieldy topics: including omnipotent algorithms, data banks on which our identities are swiped, doxed, and recorded, often with little consent, as well as the endless strings of code that underline contemporary life.

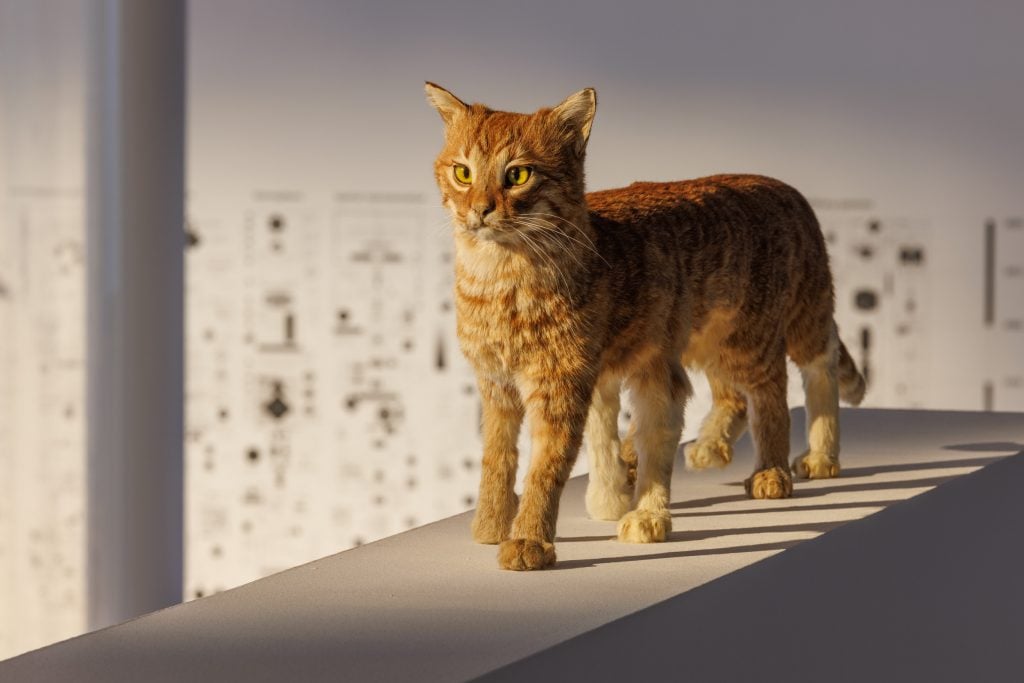

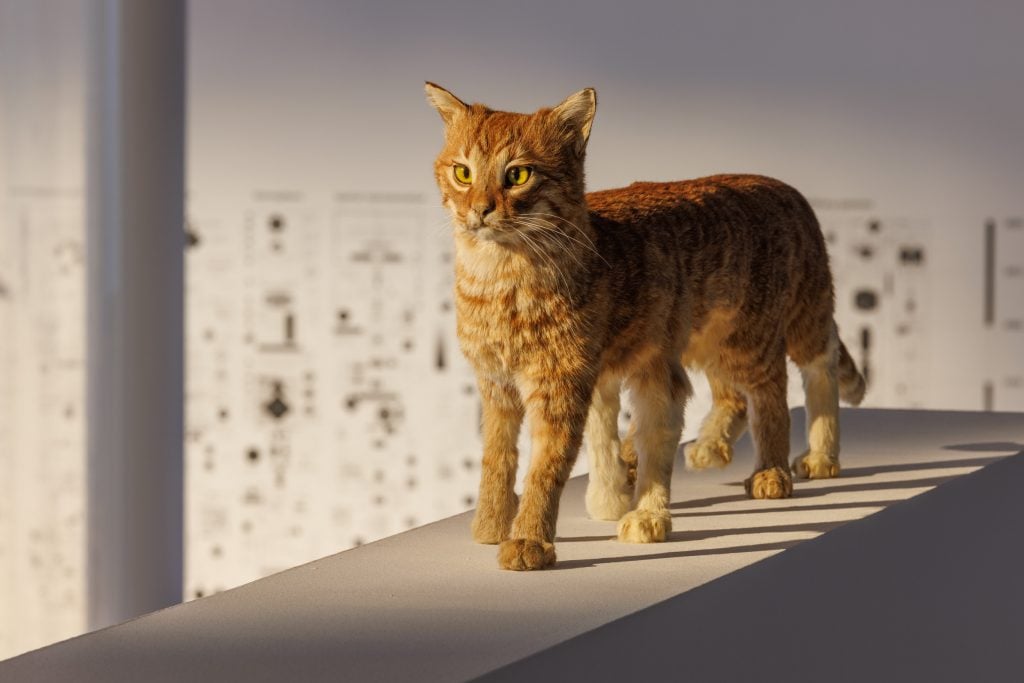

As such, darkness—a sense of non-permeable black zones—pervades the spaces by way of black walls and dim lights (so dim it makes the didactic panels too hard to read in places). It does make it hard to remember the sterility that can be associated with post-internet art. A phantasmagoric cat reappears in two transfigurations, once with eight legs and, later on, two. Both artworks by Eva and Franco Mattes, these taxidermy sculptures are based on memes called “panorama fails”—warped images that distort figures. The show, in moments, feels like one of these pictures, where works seem to echo and repeat, though I am not sure it is always intentional. Warehouse-like PVC curtains recur in several rooms with a plasticky stench, recalling industrial factories, an architectural intervention by the architect Jürgen Mayer H.

Installation view of the exhibition Poetics of Encryption at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2024; Photo: Frank Sperling

“Poetics of Encryption” has little of the standoffish aesthetic that was a prototype for the art scene and DIS-era art scene of a few years ago. The tone of that biennale on the whole (there were many compelling works), which came to be the emblem of post-internet art—largely cynical, apolitical, typified by a bit of smugness—has lost an edge. And actually, it would seem crass in the world of 2024. (Although there is Tilman Hornig’s 2013 Glassbooks, a bunch of glass MacBooks arranged on a table that recalls the merchandising of an Apple Store.)

Instead, the ethos of many artists in “Poetics of Encryption” strikes me differently from that 2016 moment—there is less celebration or naïve curiosity about digital life or the libertarian merits of crypto and online networks. One has a sense of moving through a techno-industrial landscape that meets a speculative museum of post-nature. Romanticism and, that pining sense of longing or maybe even mourning, is present in works that consider environments in states of entropy. Julian Charriere’s sculptures—faux meteorites made from trash—speak to this kind of yearning.

A.I. feels like some kind of endgame in Calculating Empires: A Genealogy of Technology and Power, 1500–2025 (2023) by Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler, which places it within a 500 years-long mind map, an expansive two-part flowchart pasted on a pair of walls that attempts to visualize the complex intertwining systems of innovation, colonialization, and technology. Carsten Nicolai’s mysterious all-black sculpture engulfs an entire gallery, driving home a feeling of ominousness, mystique, and low-level anxiety.

Installation view of the exhibition Poetics of Encryption at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2024; Photo: Frank Sperling

But if this version of the future feels burdened by the past, it’s because it is. The anti-industrialist, anarchist, and murderer Ted Kaczynski, who died last year, is embodied by Freedom Club Figure, a 2013 work by Daniel Keller that includes on a slender mannequin wearing Kaczynski’s backpack, which the artist allegedly purchased from a United States government auction.

Installation view of the exhibition

Poetics of Encryption

at KW Institute for Contemporary Art,

Berlin 2024; Photo: Frank Sperling

Rather than driving around the dubious detritus of the web, the group show steers right into it, and some of the most interesting works looks unflinchingly at the darker corners of the internet.

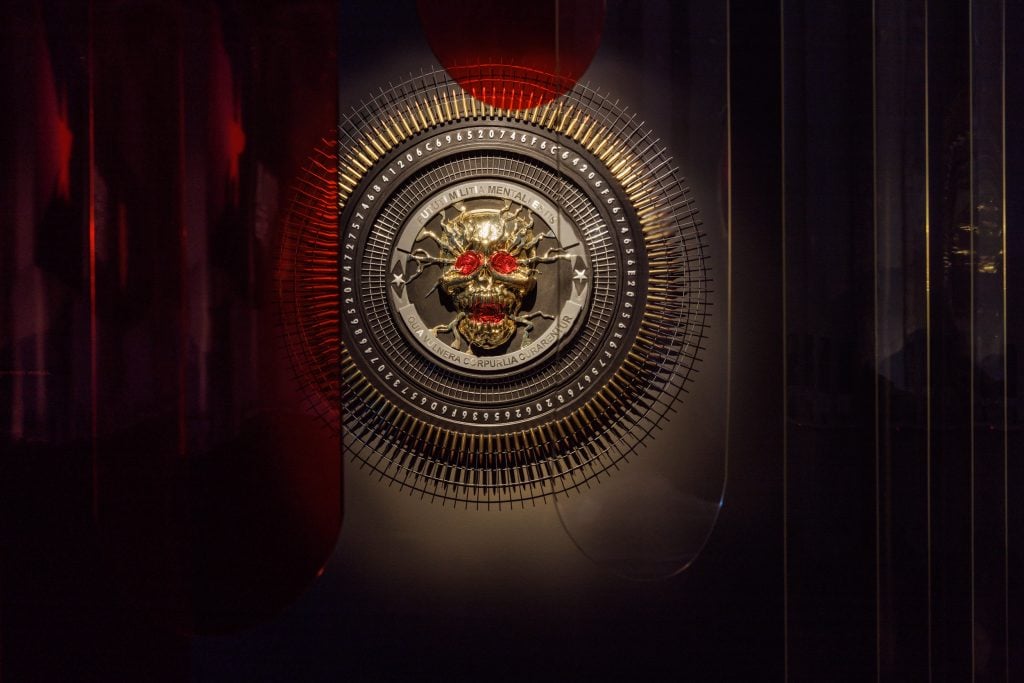

Dylan Louis Monroe, of the right-wing conspiracy movement QAnon, is not on the artist list but his deep state maps are on view, shyly relegated to a hallway, maybe because they are a bit too real. A cluster of computers reminiscent of a dank internet cafe includes several online-platform works, one of which is the very dystopian PMC Wagner Arts, a surreal (and fictional) company populated by a board that includes Peter Thiel, Yevgeny Prigozhin, and Julia Stoschek (speaking of real, the latter is actually a KW board member). A work by the art collective ubermorgen, PMC’s two-bit website veiled with corporate lingo, a very 2016 technique using a very 2024 cast of ambiguous characters.

Installation view of the exhibition Poetics of Encryption at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2024; Photo: Frank Sperling

Several works analyze political and cultural compasses retooled by algorithm and a changing society. The collective Clusterduck’s The Detective Wall (2020–24) provides a physical visualization of a thousand memes in thematic clusters, with red threads (I do appreciate the meta comment on the Pepe Silvia meme) building out a pictorial universe. According to the press text, it references Aby Warburg’s visual mapping of culture, but I might not go so far—however, I appreciate the tactile, zine-like aesthetic. Joshua Citarella’s flag series E-DEOLOGIES (2020–23) hangs in an atrium at KW, with various political insignia overlaid and reimagined as flags. His project—to crystallize a new constellation of mutating political ideologies that have emerged in online micro-communities (“Under no pretext shall we be tread on” is apparently the motto of a very emergent “Anarcho-Collectivist Capitalist Mutualist” group) codifies a political spectrum that is unraveling and rethreading itself in surprising ways.

Given the themes of this show—the web, politics, and our collective psyche as a shifty feedback loop—it is notable, then, that ubermorgen’s work caused controversy on social media when a preview of it was posted on KW’s Instagram as part of show promotion in March. It seemed to offend enough followers (who condemned the references to Prigozhin’s Wagner mercenaries) and was reported to Meta; the post was removed by its content moderators. For a show with this topic, this outcome felt almost tragically ironic. And it is striking how often it can be forgotten that the problems of the world rarely stem from art.

I wonder also if, maybe, the anger could have in part been a projection given what was happening in real-time: KW board member Axel Wallrabenstein resigned in February after inciting anger over his commentary on Twitter, which some saw as a trolling rhetoric about the Israel-Gaza war; many were infuriated by his posts, which included heart eyes and an Israeli flag accompanying footage of Israeli soldiers smashing shops and humiliating detained Palestinians.

Installation view of the exhibition Poetics of Encryption at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2024; Photo: Frank Sperling

In that fray, some of the most powerful moments in the show are not representative. American Artist and Morehshin Allahyari decided to remove their work from “Poetics of Encryption,” crossing out their names from participation as a part of strike against German institutions. “The aggressive censorship and suppression of critical voices by the German government and the support of genocide in Gaza is something I cannot tolerate,” American Artist wrote on Instagram when announcing their respective withdrawal.

This is where a struggle with media or post-internet art—how to bring the digital into the analog space in a convincing way—succeeds in the most concrete terms. There is one blacked-out screen among a series of works by other artists where Allahyari’s should have been (that said, I ran into someone who thought that screen was simply broken). In another gallery lies a crate that holds the sculpture American Artist chose to not unpack. What a shame to not be able to see the work Mother of All Demos III (2021), a computer of dirt, old parts, wood, and asphalt—a symbol of eroding modernity.

Against the backdrop of a brutal conflict in Gaza, and in the midst of a wretched German political arena marred by censorship, and a psychodrama online where artists have been canceled by institutions for comments, likes, and reposts, a question from DIS’s 2016 curatorial text, dripping as it was then with irony, comes to mind: “Are we at war?” Standing amid the hum of servers and screens at “Poetics of Encryption,” which only hint at the surrounding chaos, we can now answer from the future, this time with sincerity: yes.

The group exhibition “Poetics of Encryption” is on view at KW Institute of Contemporary Art until May 26.