Art World

Poisoned Tongues and Chicken Feet: My Sojourn to China’s Rising Kingdom of Contemporary Art

Our dealer-scribe ferrets out the news to be had in the Far East.

Our dealer-scribe ferrets out the news to be had in the Far East.

Kenny Schachter

As an art lifer, I’ve begun to measure the remainder of my days by how many Art Basel fairs I’ve left to attend. The fifth iteration of Art Basel Hong Kong (or 10th if you include pre-Basel ownership)—together with Beijing’s first Art Gallery Weekend—brought me to China this time around. For the art world, China and the region represents a new constituency with a voracious, unparalleled curiosity and hunger to learn. The military may run the biggest auction house, Poly, but who’s to judge considering what’s happening in the rest of the world? China was recently defined as constituting 20 percent of the art market in the Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report by Clare McAndrew (poached from the Maastricht fair) versus 21 percent for the UK and 40 percent for the United States. So, off I went with no clear plans and fewer invitations.

The Song dynasty, from 960 to 1279, was the first government to nationally employ the use of paper money, and begat a blossoming in the support and celebration of the arts. Emperor Huizong (1082-1135) was better known for his poetry and painting prowess than his governing capability, and during his lifetime he accumulated a collection catalogued at 6,000 works. He was the proto-Mera Rubell of the Song. One imagines that if Trump picked up a brush he’d be a more sympathetic character, too; it didn’t do any harm to George W. Bush, now the subject of a best-selling book and an exhibition of his paintings.

Since art and the trading of it burgeoned in the Song, my theory is that collecting may in fact be responsible for the conception of currency. In 2014, a federal agency declared there were more than 35,000 museums in the US, while in China today there is but a single operating state-run institution for contemporary art, Shanghai Power Station of Art. (Another is in the pipeline, M+ in Hong Kong, where ground has recently been broken.) Coincidentally, the M+ museum just announced it will have a collection of some 6,000 works of art and design on opening day. The song remains the same, but the future is infinite.

As an aside, I took the art of self-inviting to unprecedented levels, literally foisting myself into dinners, parties, and gallery excursions from Beijing to Hong Kong no less than half a dozen times. If inveigling ever became an Olympic sport, I’d be well decorated. But hey, I was there to chase stories and as trader, writer, and, er, personality—it’s entirely understandable why I’m not the most desirable party favor, or mascot. But as a dealer-to-dealer dealer that sells through many of the galleries I called upon (though not all), what choice do they have?

Beijing

In the taxi from the airport, I saw more than once the destruction of rudimentary housing in the hutongs that shape the city, endless mazes of cement shantytowns; ample police were on hand in each spot to accompany the razings. The drivers in Beijing lean on their horns as much as any other pedal, and the notorious pollution is probably the worst on earth—a one-country global warming machine. When need be, the government temporarily blasts it away, but it’s impervious, and the effort futile. In New York and Europe taxis have irritating video screens that are impossible to turn off; the Beijing equivalent are portable air filters affixed to the backs of the seats—a paternalistic gesture, if ineffectual. Craning to see some sun, I hate it when the pollution blocks out the smog.

Not a good sign (Courtesy Kenny Schachter)

The internet is exasperating too, not too dissimilar from Cuba (for now); it’s hard to imagine taking email for granted, but you do. WeChat (developed by the Chinese holding company Tencent) kind of makes up for it as a multipurpose platform that conjoins email, Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram into one. To befriend others, you scan their QR code—Quick Response Code, a matrix barcode designed for the Japanese auto industry—or vice versa, another kind of phone sex.

WeChat is part of a post-business-card-and-email universe, but Chinese custom and etiquette dictate an endless exchange of cards: my own stash ran out in days and I returned with a pile, even though I barely recall who’s who. Soon I’m sure you’ll simply shake hands and that will do the trick, digitally.

Beijing Gallery Weekend, based on the Berlin model, was launched by German writer (and artist) Thomas Eller as an attempt to help 14 local galleries increase audience share—and not just eyeballs, but bodies on the ground. For $5,000 a pop, galleries were included in the official program and invited to a gala dinner that was more a corporate mixer, but nevertheless entertaining. I was an early convert when offered transport from the airport (they were sponsored by Porsche). It’s not too difficult to sway me.

Beijingers have an enduring antipathy for the Shanghainese, whom they consider bourgeois, overly commercial, and superficial. All art is made in Beijing and exhibited in China’s best galleries there, they’d have you think. But I visited plenty of galleries, private museums, and artists in Shanghai as well, and the two cities are clearly embroiled in something like the old East Coast-West Coast rap rivalry in the states. In either case, we art-worlders don’t skip many opportunities to do business while partying like it’s 1999, i.e., ferociously, and that’s what we did.

Beijing taxi air filter (Courtesy Kenny Schachter)

Manuela Hauser and Iwan Wirth of Hauser & Wirth celebrated their 25th anniversary with dinners in Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. I managed an invite to the first leg of the festivities in a restaurant located in an exquisite ancient temple in Beijing, but like an eccentric uncle turned up at their hotel the following day to join their next excursion, too, largely unbeknownst to the gallery. Iwan is only 47 but he’s been at it for years. I joked he must have started at 15, and I wasn’t far off—at that very age he called upon Swiss painter Martin Disler to organize an exhibition, only to be shot down. Not long afterwards he traveled to Egypt to pursue another artist who ultimately granted him a show that Wirth presented in his Zürich apartment.

The first location of our whistle-stop tour was to the studio of Zeng Fanzhi, among China’s most celebrated contemporary artists—and, with an auction record of $23.3 million, the most expensive. It was an auspicious start. A collector onboard offered to send a group studio portrait to Gagosian, the artist’s primary representative. Rich as the painter obviously is, all I saw was purity of intent and a profound passion (and an elegant Morandi). It was a common thread throughout my trip—the enthusiasm, that is.

The Ullens Center for Contemporary Art staged a group exhibition entitled “The New Normal,” which for the trailblazing institution also alludes to the fact that a buyer for the museum still hasn’t been found, even though it’s been dangling on the block for some time. Standouts included installations by Cui Jie (she’s got an architectural Enoc Perez thing going on) and Gao Lei.

Philip Tinari, the museum’s director since 2009, is an Oxford-educated intellectual who is about to co-curate “Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World” at the Guggenheim in New York next fall. That upcoming show, organized with Alexandra Munroe, is named after a work by Huang Yong Ping (who is featured at Art Basel Hong Kong at Kamel Mennour Gallery) in which live scorpions, beetles, and other insects battle it out in a real-time life-or-death match. The artist might have pursued art dealing instead.

By the way, in what can only be termed the most illustrious ad-hoc membership drive in museum history, when Apple’s Tim Cook and his entourage rocked up to the Ullens they were all forced to join to gain admission to the preview. On the bright side, Cook must have been heartened to see the preponderance of tech-infused art.

By day’s end, I was privileged to have been a member of Team Hauser, if only for a (relatively) brief period; as a group, they were warm and familial, and I was grateful to tag along. Manuela, Iwan, and their dedicated staff have a childlike sense of wonderment and patience to pay attention, both of which vastly outstrip mine, and their joyful enthusiasm for seeing new art and artists was infectious. I can’t thank them enough—they really are a family affair, albeit a 200-strong army of a clan. Here’s a scoop, between us: look for Hauser’s next outpost in Hong Kong. By the way, when Martin Disler passed away in 1996, Hauser refused the estate.

Miao Ying at .com/.cn organized by K-11 and MoMA PS1 (Courtesy Kenny Schachter)

Later on, the Art Weekend dinner was chockablock with collectors, dealers, and the kind of young artists—straight from central casting, with their filthy clothes and artfully unkempt hair—who are filling the city’s private museums, a downright proliferation. Ubiquitous Klaus Biesenbach was on hand (who together with Hans Ulrich Obrist constitutes the dynamic duo of globe-trotting curocrats), checking placement settings before the ball kicked off to confirm seating hierarchies. (I may have been doing the same thing moments before.) I’m warming up to Klaus and his free-reigning curatorial style. All that paling around with celebrities paid off and Bisenbach has become one in his own right, a curatorial Svengali to art’s up-and-coming buyers and makers, casting his spell from Germany to China. He’s better at it when working with artists as opposed to… oh never mind. During the Art Weekend, he had his fingerprints on the Si Shang Art Museum video show and had co-curated a thoughtful show (if raucous with gifs and videos) in Hong Kong for the K-11 Foundation.

Throughout my trip from Beijing and beyond, I encountered an endless barrage of readers of my column (it’s been translated into Chinese for some time) who felt no compunction in expressing feedback—or pushback?—and rightly so. Such a reaction is in the vein of my voice, so touché. Here is a taster, but by no means the full smorgasbord: “You are shorter than I expected”; “Ah, here is the poisoned tongue”; “You don’t look funny”; and on and on. A previous column I wrote about Shanghai even became a bone of contention. I was beginning to bore and disgust myself. I never meant badly, I love what I do, art, and even the market. I can’t help myself pulling back the curtain to reveal mystic truths (as Nauman might say) about the machinations of the market, and my reputation seems to have preceded me. “Oh, it’s you!” said a journalist of a prominent Chinese art publication upon making my acquaintance; later that night, a friend of a friend cancelled dinner because I was on the menu. Yikes.

Simon Fujiwara at Beijing’s Si Shang Museum (Courtesy Kenny Schachter)

Si Shang Art Museum, on the far-flung North 6th Ring Road of Beijing—the last of the concentric loops that comprise the layout of the city—is a 400,000-square-foot art museum with a residency program, library, and built-in onsite freeport, the best of all possible worlds. Started in 2010 by the family of Linyao Kiki Liu, the daughter who contemporary-ized the space (she’s a closet painter), Si Shang is a Los Angeles-scaled former food-canning factory that showcased the most spaciously, generously installed video show I’ve ever seen, each piece accorded the equivalent of a vast hall. It was in itself amazing, and a sign of things to come, ranging from Virtual Reality to the multichannel to the multi… everything. That’s even though I’ve never been a video fan—I term art that has to be turned on (and off) “cocktail-party art.” I’m a prude, and prefer pigment and pencils. Some of the Si Shang displays I wouldn’t watch twice, but I’ve never seen a better-composed media show, other than Vito Acconci at MoMA PS1, another Biesenbach enterprise. (I sound like a fan.)

Hong Kong

The gruffness of Hong Kong taxi drivers almost exceeds those of Beijing. When a cabby deemed my destination too close, he pressed a button that swung open the rear door—an ejector-door—and barked in Chinese: “Walk!” The trick to HK is knowing when and where you can cross the street, which is not as straightforward as it sounds and entails countless enclosed, claustrophobic walkways. It’s baffling and makes New York feel like a walk in the park. Streetlights are equipped with an audio component for the visually impaired that resembles the sound of chattering teeth, and which I could hear from my hotel room. (In fairness, it seems my writing has the same effect on many.) Trying to get around the city by Google Maps is hopeless due to the height of the buildings, causing me to chase my tail trying to find a lunch until I melted in the rainforest-like humidity.

As for Art Basel Hong Kong itself, it was refreshingly less European and American this time around, but there were still plenty of well-known faces, including Jeffrey Deitch, Francesco Bonami, Stefan Edlis, his wife Gael Neeson, and a group of museum trustees from the New York’s New Museum. In the art department, an mixture of obvious and less so Western work was on display alongside a respectable array of regional material. Exhibitors approached the fair with better art than in fairs past, for a more informed crowd; as one put it, dealers realized they are not selling to suckers (anymore). Dare to say, I found this Basel as interesting as Basel-Basel—even more interesting, perhaps, by way of seeing, learning, and meeting the unfamiliar. The gallerists were reaching higher than ever before in terms of the quality of their offerings. There were also an awful lot of Australians on hand, due to proximity. Art Basel HK is Miami Basel for Australians.

As much as the American and European collectors are fair-fatigued and weary, the Chinese were left to pick up the slack, and did so with aplomb. A participating dealer (from LA, obviously) spoke of the “super-stoked energy” on the floor, and recalled a collector who taught himself English over the course of a year to better negotiate, and who happened to refer to my writing as “rough trade.” Argh. Monumental amounts of mints were consumed on the floor, an integral ingredient of any fair—but beware, I read that synthetic sweeteners can “hinder digestion, cause bloating, and prevent fat burning.” Top quote overheard: “The best way to make friends and never pay for a meal is to spend $500,000 at a gallery—and you never even have to buy another work!” If dealers gave out credit-card-style loyalty points it could hardly be a more effective inducement.

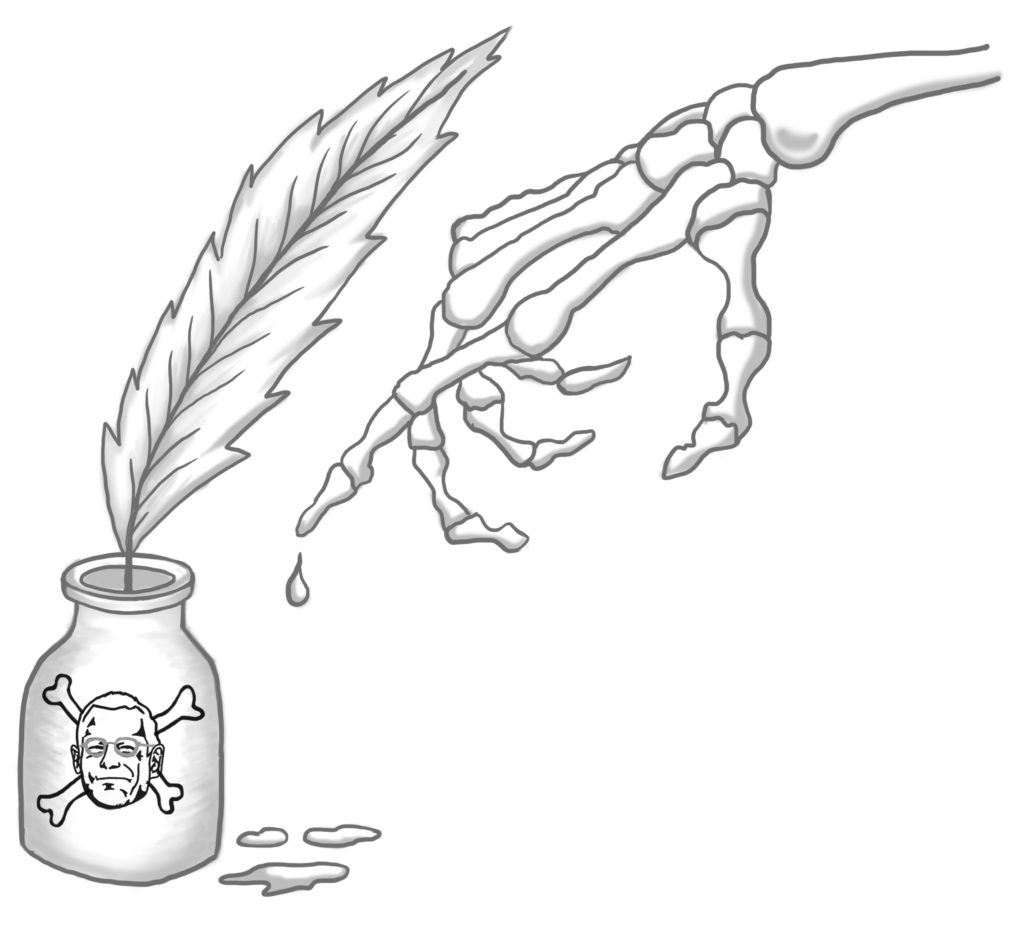

A few fairs ago, I poked fun at Fergus McCaffrey Gallery of New York about a recurring Sigmar Polke diptych that went directly from auction to a series of fairs under the tutelage of McCaffrey, at a hiked-up price. It’s a good little painting, albeit a tough one due to the murky colors. The 1983 diptych ($1.3 million asking price) has become like a member of the gallery—it should have its own fair passes. When I asked after another Polke at the booth, Fergus started to make incomprehensible sounds, like a steam engine getting underway, before he blurted: “You trashed my Polke in the past, why should I tell you!” Though he looked combustible, I persisted: “How much is it, $2,000,000? C’mon….” He shot back: “It’s yours if you want to pay that.” I heard Fergus described as ornery and argumentative by more than one. I’ve begun to admire him. In all seriousness, he had an astounding booth, presenting a solo show of Toshio Yoshida (1928-1997), an unheralded Gutai artist, if there are any left. Abstraction with mixed media such as rope, the paintings were colorful, kitsch, and serious simultaneously, and pegged between $20,000 and $80,000 seemed a bargain. And I was later informed that tucked in the closet was the very Polke diptych that elicited his near-apoplectic response. Time for a rest, it seems (for both).

Toshio Yoshida painting at Fergus McCaffrey (Courtesy of Kenny Schachter)

Bookending my entire nine-day trip was a seemingly imploding deal characterized by money-chasing, parsing false promises, and damage control after it emerged that the work was being re-offered before it was paid for. I went to a gallery dinner at a local restaurant (I was actually invited to this one) and a dog-sized cockroach dropped from the ether onto my plate: I felt like I was in a Huang Yong Ping piece engaged in bare-knuckled, mortal combat. I was, in effect, with a handful of venomous art dealers looking for blood—mine. As the multiple parties on hand were waiting to be paid in my painting sale—past the expiration of previous promises to do so—a SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) confirmation appeared on my phone, but even that’s not enough until the credit is reflected in the account. I’ve seen dealers Photoshop transfer receipts in the past. This grief is unfortunately a component of just about every deal I’ve been involved in.

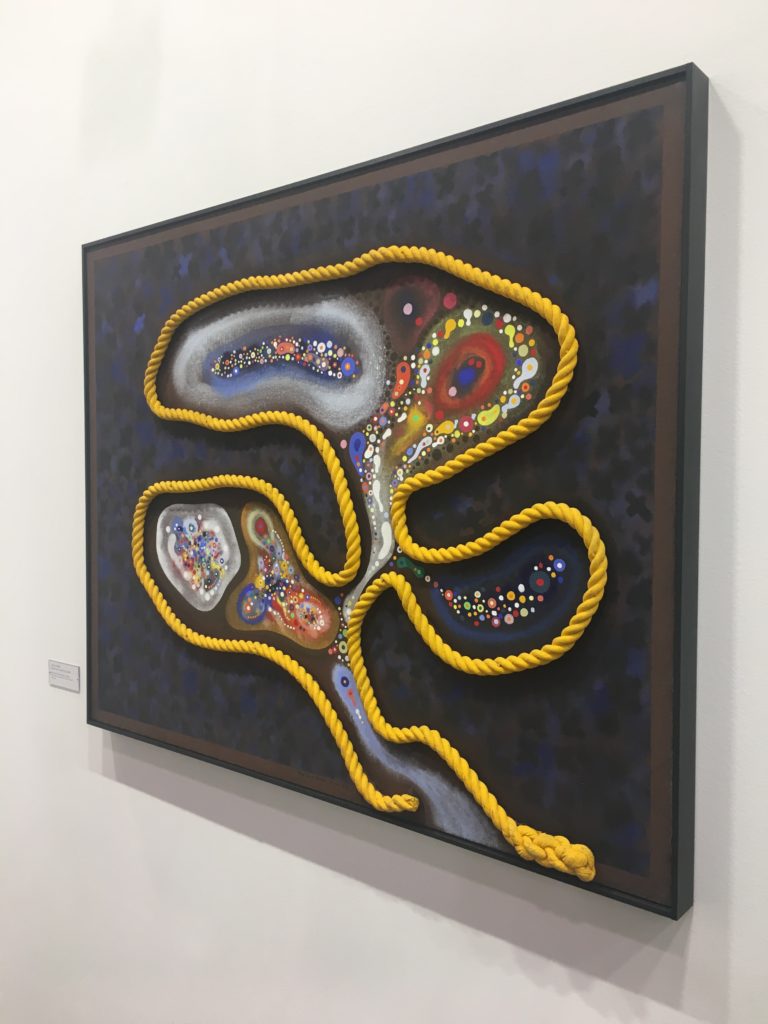

Zaha Hadid (detail) at ArtisTree, Hong Kong (Courtesy Kenny Schachter)

Artis-Tree (surely they could have done better in the naming department) is a space run by the Swire group, a huge conglomerate launched in 1816 by Joh Swire, listed on the Hong Kong exchange, with humble beginnings in Liverpool of all places. (I sound like Hans Haacke… who should consider an investigative piece on trade in China.) Hans Ulrich Obrist, in his best accidental Godfather imitation, told me it would mean a lot if I viewed the Zaha Hadid show that traveled from the Serpentine to HK. It was an offer I couldn’t refuse and, besides, I relish any occasion to visit my beloved friend Zaha. I even donned the Virtual Reality goggles, an increasingly ubiquitous accessory in exhibitions nowadays; the guide told me no glasses, however, so I had to squint to see a building shard neatly hit me in head. Someday there will come a masterpiece from VR, not just yet.

The Peak, Zaha’s renowned unrealized HK house, was commissioned by Alfred Siu, the very young and debonair resident who welcomed Andy Warhol on his trip to China—a sojourn that was the subject of a Phillips auction house photography exhibit in the lobby of the Mandarin Oriental Hotel. Siu was advised back in the early 1980s by Jeffrey Deitch, who figures in one of the Warhol photographs, which reveal themselves in the show to be casual holiday snaps.

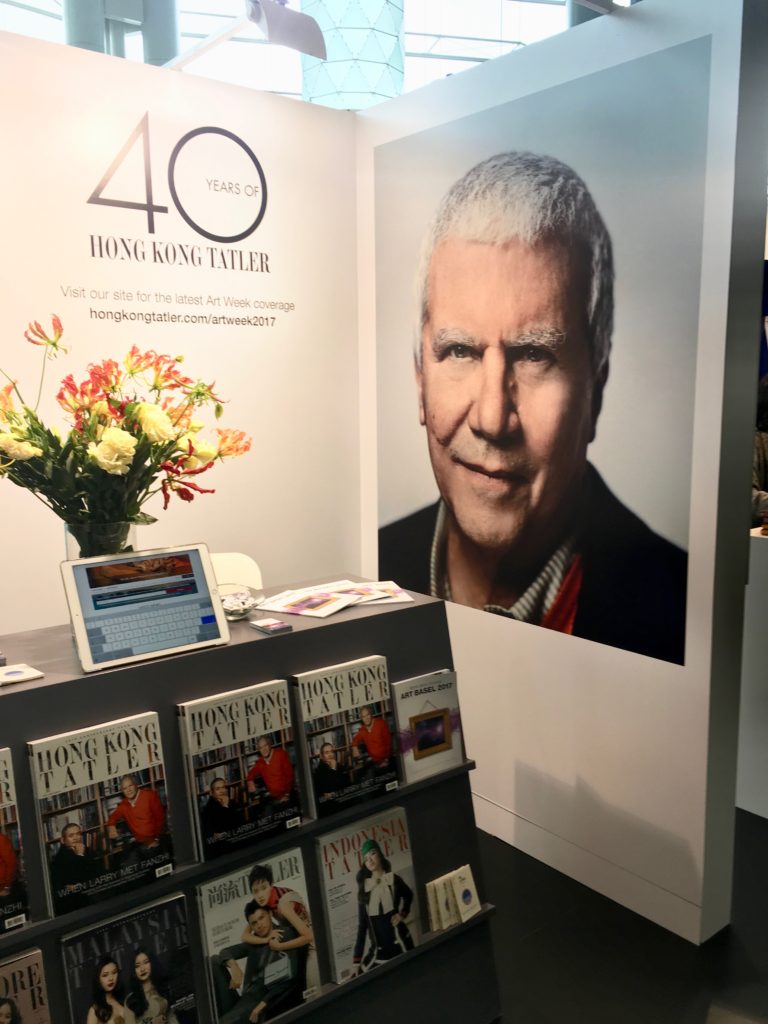

Larry G. poster (Courtesy Kenny Schachter)

Beijing and Hong Kong were a rollicking ball, and I even managed to contribute to an Arte (the Franco-German TV network) documentary on Larry G. that charts his rise from selling posters to poster boy, literally—Tatler Hong Kong used him in their advertisements plastered in the lobby of the Art Basel exhibition halls. I have only admiration and respect for the model dealer. Back on point: the two biggest changes I’ve witnessed in 30 years on the job are Instagram, where each day everyone can find a tailored art show (and tell), and the growth of Asian demand for international art. Look for the Chinese market to double in five years—mark my words. As gallerygoers, and people, we are very much the same. Perhaps not, however, in their yen for the delicacy of crispy chicken feet, where a thin film of meat between skin and paws (tendons) must be sucked to extricate the morsel, while spitting out bone pieces in the process. I must hand it to them for being non-wasteful of the animal’s totality, but, as a pescetarian, I prefer my food with no feet.

Chinese chicken feet (Courtesy Kenny Schachter)

China now has its place firmly inscribed on the art map, the significance of which the industry—or anyone else, for that matter—can’t afford to ignore. An Uber driver called the Hong Kong Basel fair the busiest week of the year in an already “quick-on-steroids, vibrant, fast-paced city.” I’ve put down my poison pen, fully appreciative of how very lucky I am to do what I do and to do it in places such as Beijing, Hong Kong, and Shanghai, too (despite the backlash experienced there). As I boarded the plane home, the crew passed through the cabin spraying pesticide—it made me nostalgic for chicken toes, which I would prefer—but even that couldn’t dampen my enthusiasm for the trip and my imminent return to China. That, plus I finally managed to close the deal that bedeviled me throughout my trip. The funds, unlike Beijing’s pollution, cleared.