Art World

The Riveting Stories Behind 5 Art Historical Masterpieces, From ‘American Gothic’ to Leonardo da Vinci’s Vision of Cecilia Gallerani

A new book by Francesca Bonazzoli and Michele Robecchi explores these pictures and others.

A new book by Francesca Bonazzoli and Michele Robecchi explores these pictures and others.

Caroline Goldstein &

Eileen Kinsella

In a beautifully illustrated new book, Portraits Unmasked: The Stories Behind the Faces, authors Francesca Bonazzoli and Michele Robecchi give readers a glimpse into the illuminating narratives driving some of the best-known paintings in art history.

“The ancient stories of Pygmalion and Faust, the creators of the golem in Jewish legends and even the biblical tradition that has God moulding Adam out of clay seem to suggest that picture-makers have always had the upper hand over their subjects,” they write in the introduction.

The book probes the pas de deux between artist and sitter—that distinctive dance of “fear, flattery, gratitude, and mistrust” between two people spending hours together in pursuit of the perfect portrait.

Below, we take a look at some of the most compelling artworks discussed by the authors, and highlight the incredible stories behind their creation.

It all started when Milan’s arrogant ruler, Ludovico “il Moro” Sforza, thought he could pull off the impossible: have his wife and his lover—a beautiful, intelligent young woman from the Milanese court named Cecilia Gallerani—live together under the same roof.

Sforza hired his favorite artist, Leonardo da Vinci, to paint Gallerani’s portrait, which he completed before she became pregnant with the ruler’s son, Cesare. The ermine, said to be a stand-in for Sforza, “had the same liveliness and rapacious expression as Ludovico,” Bonazzoli and Robecchi write in a chapter appropriately titled “Love Will Tear Us Apart.”

Sforza’s wife, Beatrice, tolerated the uncomfortable arrangement for a while, even allowing the illegitimate son of her husband and Gallerani to appear in court. But when Beatrice saw that both she and Gallerani had dresses made of the same cloth, she threw down the gauntlet and demanded that the Duke send his mistress away. Cecilia took the portrait with her when she left in 1498.

A trailblazing nonconformist, the artist Hannah Gluckstein would only tolerate being addressed as Gluck, sans any gendered modifiers. Though her early output was almost exclusively botanical paintings and banal flowers, that changed in 1936 with her double portrait, Medallion (YouWe).

The painting depicts the artist (with close-cropped, dark hair) dressed in a man’s tailored suit, and her lover, the American socialite Nesta Obermer, painted in profile, almost like a shadow or echo of Gluck. The two women fell in love almost immediately upon meeting. They shared a love of opera, and Gluck memorialized their partnership in this painting following a weekend of taking in musical performances together in 1936.

But Obermer was accustomed to her privileged life, thanks in large part to her in-name-only husband, and she and Gluck eventually parted ways. But the artist’s longing for her former lover never diminished, and her eventual partner, Edith Shackleton Heald, resented their relationship until Gluck’s death.

Upon its public reveal, American Gothic was lost on many viewers who assumed that the portrait depicted husband-and-wife farmers. But Wood intended something else: to create an image of a father and his daughter. There was a gap of 32 years between the models: his 30-year old sister, Nan Wood, and a local dentist and friend of the artist, B.H. McKeeby.

“Something must have gone wrong in Wood’s execution,” Bonazzoli and Robecchi write in their book. “Or maybe not, given the painting’s success.”

Wood, anyway, was not terribly bothered about this misperception. His main goal was to underscore the Puritan roots of American culture and to depict the archetypal simple family. The picture, now one of the most imitated and parodied works in modern history, is today housed at the Art Institute of Chicago, where the artist began his career by taking an evening course in painting.

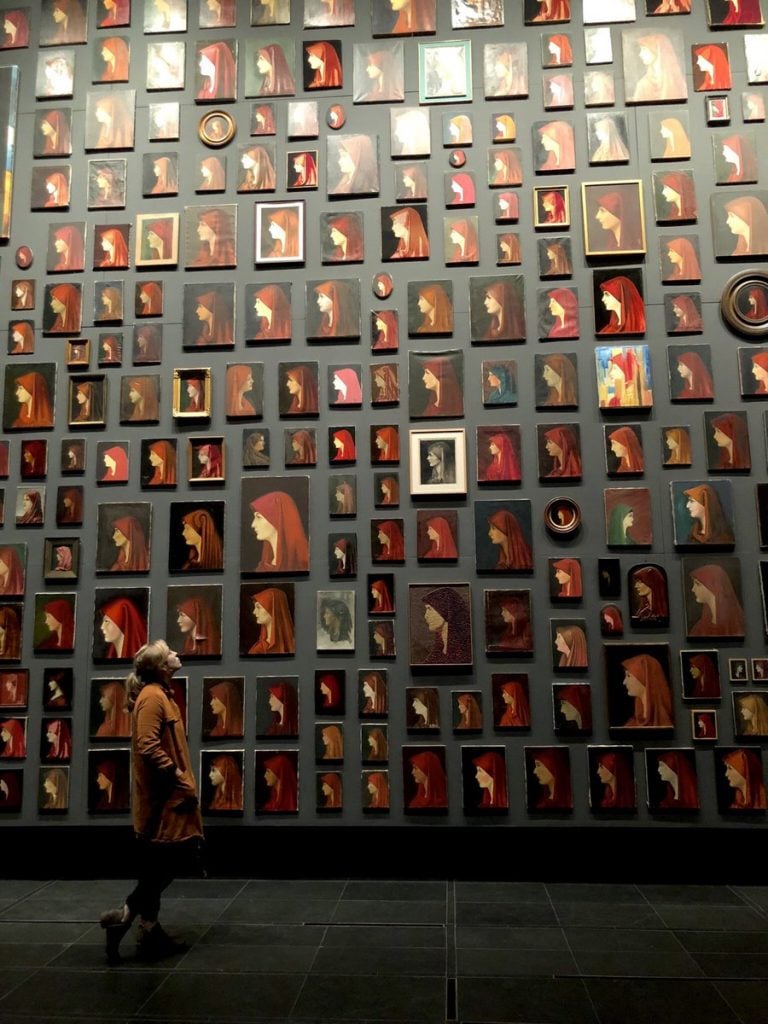

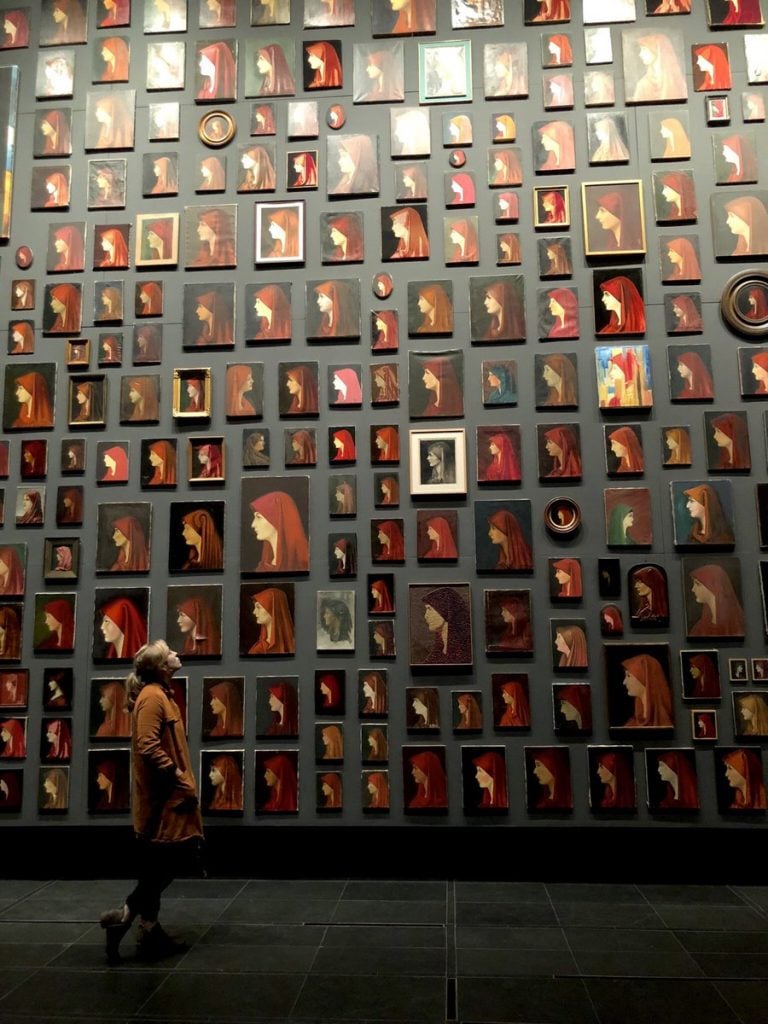

Upon moving to Mexico City, the Belgian artist Francis Alÿs found himself roaming flea markets and artisan stalls, combing for reproductions of famous Renaissance artworks to start his own collection, when he noticed a strange pattern.

“The undisputed star was instead an unassuming, left-facing profile of a nun wearing a red headscarf, who appeared to be available in every conceivable format, size, and medium,” Bonazzoli and Robecchi write.

The woman was St. Fabiola, an Italian nun whose unhappy marriages drove her to the church, whereupon—after forging a relationship with St. Jerome—she decided to put her wealth into a hospice for sickly pilgrims visiting the Vatican. Following her death in 399, Fabiola was canonized.

Around 1,500 years later, the artist Jean-Jacques Henner, a painter of religious figures and an advocate for female artists, chose Fabiola as his subject. His painting was mysteriously lost in the midst of a 1912 auction in Paris, and copyists the world over seized on the opportunity to cash in on reproductions. Alÿs has now amassed more than 450 depictions of the saint.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Hollywood Africans (1983), courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ ADAGP, Paris. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Basquiat’s meteoric rise to fame around 1980 was not without drawbacks. Having led a peripatetic lifestyle as he became famous for his street tag, “SAMO,” he suddenly found himself thrust into the center of the contemporary-art spotlight.

“Dealers were supportive but demanding, and exploitative; fellow artists were congratulatory but jealous; pressure to ‘keep it real’ and not ‘sell out’ was strong,” Bonazzoli and Robecchi write.

Basquiat was keenly aware of his surroundings, perhaps even more so when he took a trip to Los Angeles with fellow street artists and close friends Toxic and Rammellzee. Hobnobbing with Hollywood stars turned out to be even more of a reality check—and thus, Hollywood Africans was born.

Amid references to Sunset Boulevard and the Hollywood Walk of Fame, the artist included a nod to 1940, the year that the first Black woman, Hattie McDaniel, won an Oscar, for her role in Gone With The Wind.

Francesca Bonazzoli and Michele Robecchi’s Portraits Unmasked: The Stories Behind the Faces is on sale now.