On a summer night in June 1969, New York City police officers raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village. For the cops, it was routine—roughly once a month a team would raid the mafia-run establishment, seizing alcohol (Stonewall didn’t have a liquor license), cuffing cross-dressers, and often taking a cash payoff from the owners. But for the patrons—some 200 gay men, lesbians, drag queens, transgender people, prostitutes, and others—it was the last straw. Tensions mounted, crowds grew, violence ensued. The riots lasted several days, on and off.

While the organized fight for gay rights went back more than a century, the Stonewall Uprising was the catalyst of the modern LGBTQ liberation movement. Organizations like the Gay Liberation Front were created in its wake. Newspapers and magazines were launched. Pride marches became a yearly staple in cities around the nation.

The incident and the reinvigorated fight for gay rights that followed had a huge impact on artists, as it did on the culture at large. Yet, within the art historical canon, this impact has been largely been overlooked. What defines this era in art? What are artists central to its evolution? What themes do they address? What subjects do they depict, and why?

“Art After Stonewall, 1969–1989,” a landmark show organized by the Columbus Museum of Art and now on view in two parts at the Leslie-Lohman Museum and NYU Grey Art Gallery, seeks to answer these questions. Co-curated by artist and historian Jonathan Weinberg with Tyler Cann and Drew Sawyer, the show brings together 250 works of art made in the two tumultuous decades after the riots. It’s loosely grouped into themes, and brings together both the artists we often associate with this era—Robert Mapplethorpe, David Wojnarowicz, Keith Haring—and many others that we don’t.

“Art After Stonewall” has been a critical hit since it opened in April, and it’s not hard to see why. More than just plotting this moment on the art historical map, it taps into sentiments that remain culturally salient in our current time. “We’re obsessed with autonomy right now,” Weinberg tells artnet News. “People are very anxious and feel like they have no control over their lives, so we look to these moments in time and we see them as a declaration of selfhood.”

Weinberg is quick to note that this period doesn’t constitute a movement, per se—there are no set rules, there is no program or definitive aesthetic. So what is it?

To find out, artnet News spoke with Weinberg to look at some—but certainly not all—of the predominant themes in the art made after Stonewall and before the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s.

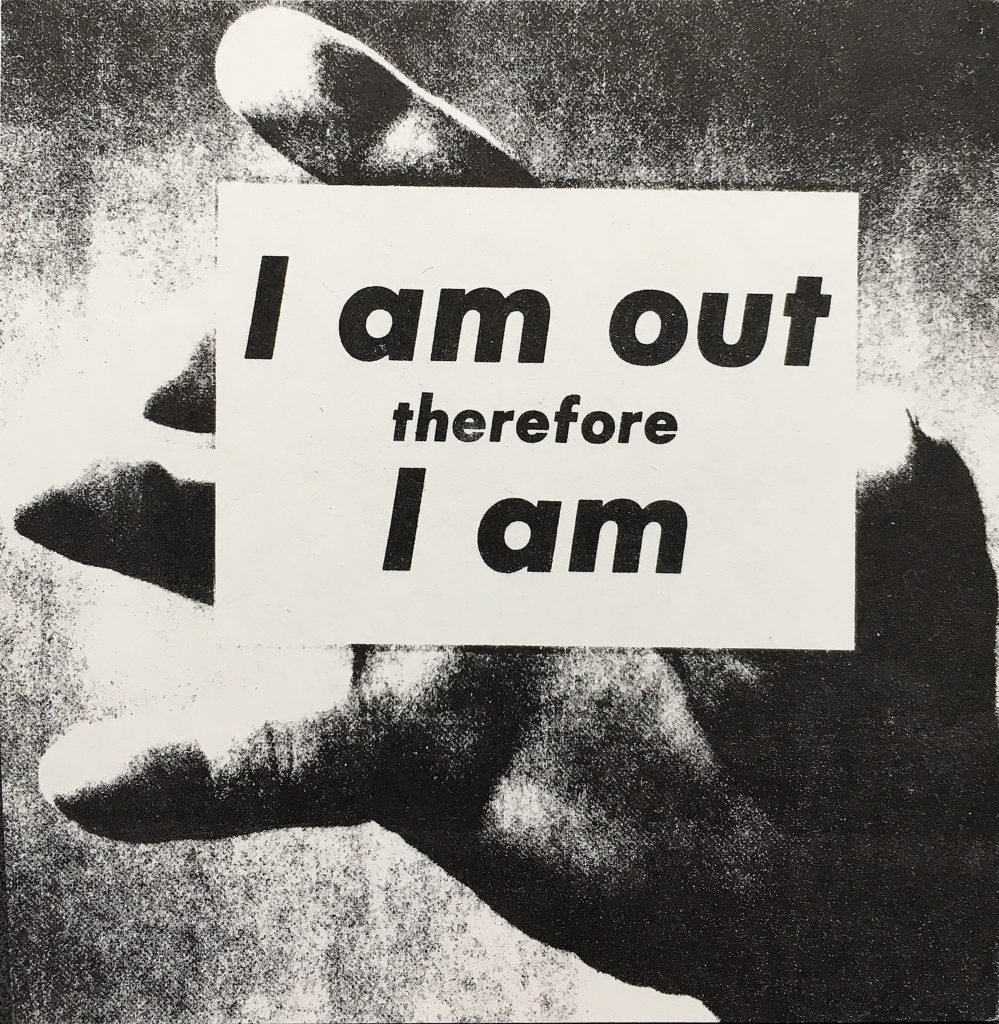

Coming Out

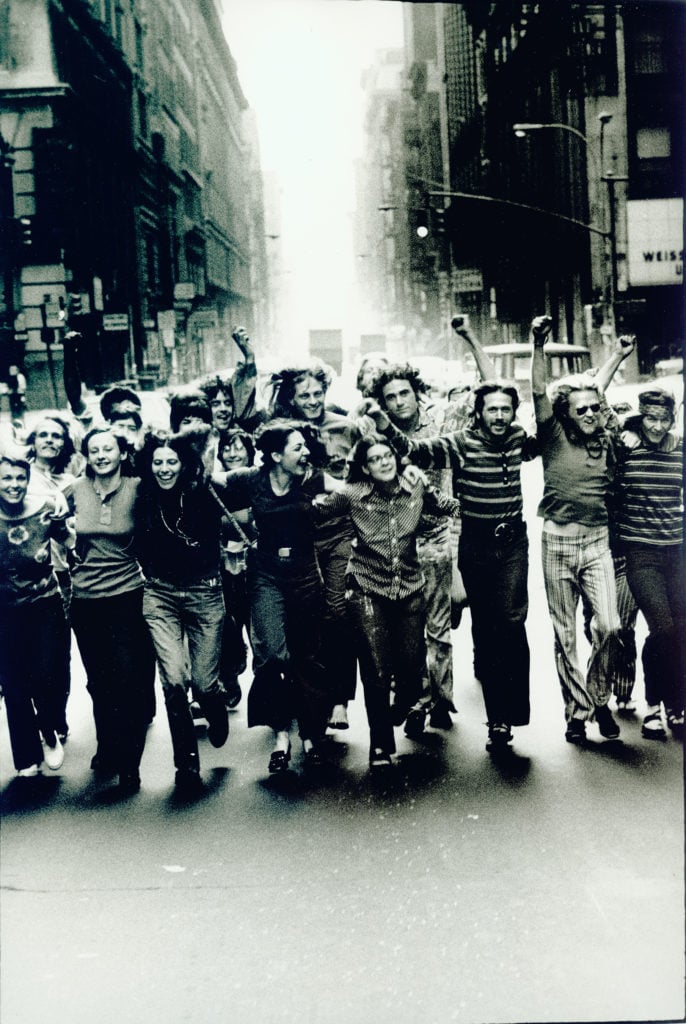

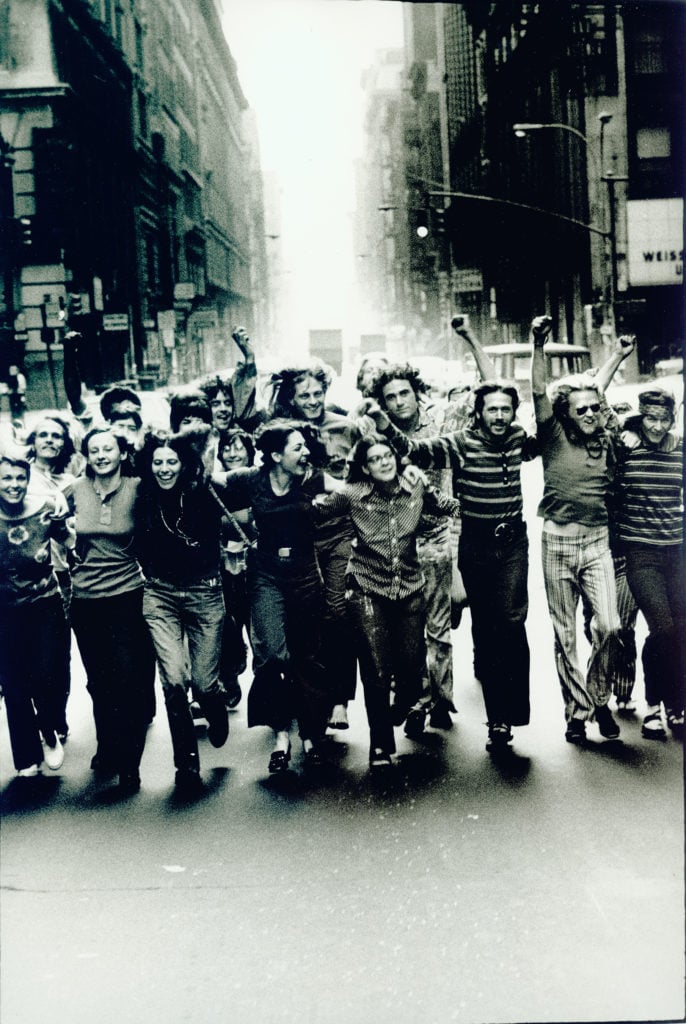

Peter Hujar, Gay Liberation Front Poster (1970). Courtesy of the Leslie Lohman Museum.

The fight for gay rights goes back much further than in 1969, but it was during this period that the notion of “coming out” took hold. “That is a huge transformational idea in the history of gay rights,” says Weinberg. “What begins to happen in the late ’60s is the notion that, in order for there to be a transformation in the gay movement, in order for us to make a difference, we have to come out.”

“So much of the work in ‘Art After Stonewall’ is declarative. It’s saying, ‘Here we are,’ or, “This is who we are,’ or, ‘This is what we want to do, this is what we feel.’ A lot of it is about visibility and the creation of a community.”

To illustrate this idea, Weinberg points to one of the most iconic images of the post-Stonewall era: the recruitment poster for the Gay Liberation Front. Photographed by Peter Hujar and designed by his partner at the time (and Gay Liberation Front founder) Jim Fouratt, the poster shows a couple dozen young people careening down an empty New York street, as if in a public march. But the image is not from a march. Rather, it was organized in the early hours of a normal morning, when Fouratt brought together a group of his friends.

What we take for granted about this photo is just how gleeful everyone in it is. Today, we might associate Pride with happiness, but that wasn’t always the case.

“They don’t want to look like an earlier generation of people fighting for gay rights,” Weinberg explains, “which would have meant wearing ties and jackets and looking very serious and heterosexual. They look like hippies— pretty hippies, young and beautiful. In a certain way, that might have gotten in the way of it being considered serious. We’ve been told through formalism that art that has too much of a single message or is propaganda is a problem. But I think a lot of that hierarchy has begun to drop from the art world actually.”

Not Asking Permission

Shelley Seccombe, Pier 52 (1978). Courtesy of the artist.

Another idea embodied by the Hujar photograph is that of occupying public space. No longer were gays gathering in special bars or private communities. They were taking to the streets.

“These were spaces that were policed and under control of the government,” says Weinberg. “In the ’60s, the idea was not to frighten anybody. In the ’70s, no one was asking for permission.”

New York’s west side piers, a derelict gay haven in the ’70s and early ’80s, is a perfect example of this, says Weinberg (who also published a book about the piers this spring). In 1973, a cement truck caused a section of the elevated West Side Highway to collapse, resulting in the closure of the southern stretch. Below, abandoned industrial spaces and rundown concrete outcroppings along the Hudson River became a hot spot for cruising, drug-using, and sun tanning—and an arena for making art.

Weinberg points to artists like Vito Acconci, who used the site as a setting for performance pieces, or Gordon Matta-Clark, who sliced open an adjacent industrial building as one of his own conceptual works. Meanwhile, a number of photographers trained their lenses on the piers and its denizens. Leonard Fink got up close and personal, shooting friends fornicating or sunbathing nude. Alvin Baltrop photographed from afar, imbuing in his images a sense of voyeuristic desire.

The Taboo

Catherine Opie, Raven (gun) (1989). ©Catherine Opie, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

It’s not a coincidence, of course, that the gay liberation movement took off on the heels of the sexual revolution of the late ‘60s. The breaking down of traditional gender constructions in art was part and parcel of a larger quest to undo sexual mores.

“It’s worth remembering that in 1969, in most of the United States, homosexual acts were illegal even in the privacy of one’s own bedroom,” Weinberg writes alongside Anna Conlan in the catalogue for “Art After Stonewall.” “For many artists, being a sexual criminal was a badge of honor.”

Two dedicated sections within the show, “Sexual Outlaws” and the “Uses of the Erotic,” look at artists trafficking in this space. Artists such as Nancy Grossman, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Tee Corinne honed in on fetishism, bondage, and sadomasochism as a means of pushing the limits of taboos. Others went for the overtly sexual, such as Lynda Benglis, who took out an ad in Artforum to run a nude picture of herself inserting a double-headed dildo into her vagina.

On the other hand, there are the artists who turned to the spiritual power of the erotic. “There’s a physicality, a sensuousness to art-making and the spirit that comes through in the works themselves,” says Weinberg, alluding to artists like Mildred Thompson and Harmony Hammond. “It isn’t necessarily genital or about having orgasms, but it might be.”

Fun!

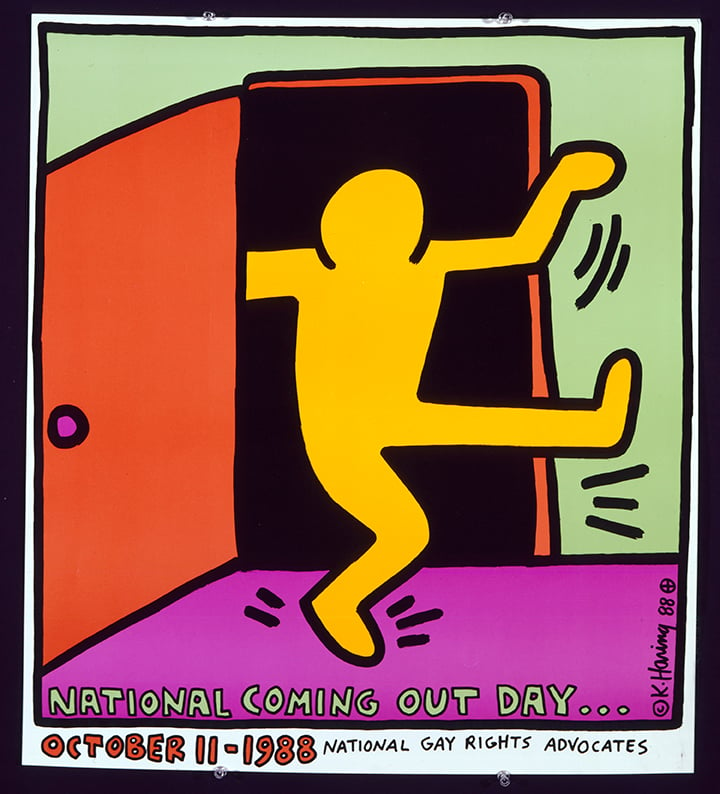

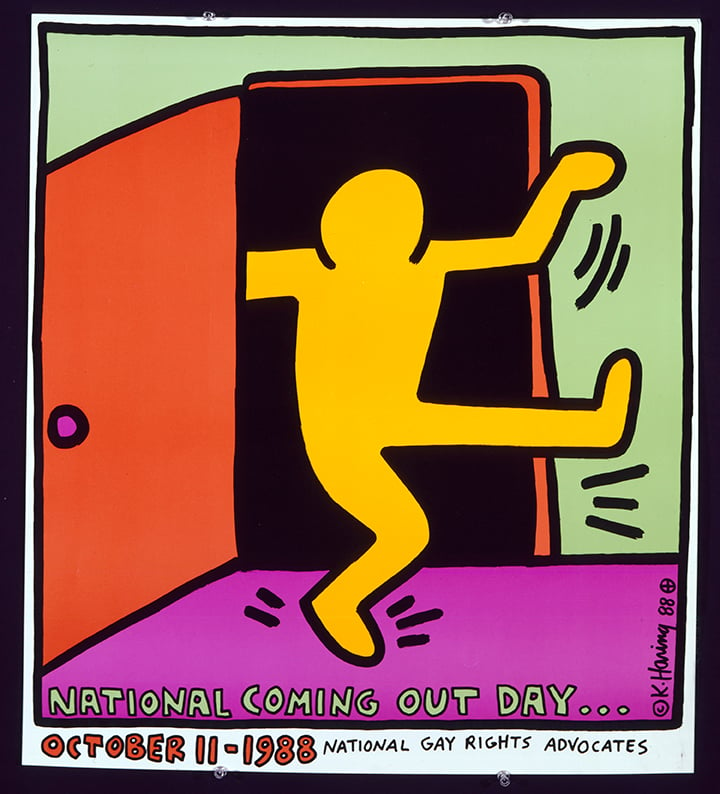

Keith Haring, National Coming Out Day (1988). ©Keith Haring Foundation.

While heady conceptualism weighed down the art discourse in the late ‘70s and early ’80s, a nascent downtown counter-sensibility emerged at the same time. “It was the deflating of the establishment, a breaking down of hierarchies, a crossing of media,” says Weinberg. “There was an explosion of galleries in the East Village. You could put anything on the wall. Painting was back. It was all noisy and busy. It was not sanctioned by the so-called ‘academy’ in any way—and that was the point.”

Keith Haring was spraying up the city streets on his way to discos. The career of Andy Warhol, who by the mid-’70s was thought of as a has-been, was resurrected. Jean-Michel Basquiat, derided by left-wing art critics as a sellout, exploded.

“There was a glamour to it all, which the New York intellectual art world thought was corrupt. There was a certain kind of idea about what was and wasn’t acceptable behavior, and then you have a young generation of artists coming in and saying, ‘fuck that.’”