The first state-owned contemporary art museum in mainland China, Power Station of Art in Shanghai (PSA) celebrated its 10th anniversary in 2022. Housed in the former Shanghai Nanshi Power Plant, once the Pavilion of Future at the 2010 Shanghai World Expo, the museum has branded itself as “Shanghai’s generator for its new urban culture” that, over the past decade, has become a central hub of the city’s art scene.

Besides hosting the Shanghai Biennial, PSA presented exhibitions of local and international artists not limited to Liu Xiaodong, Ai Weiwei, Shirin Neshat, and Anselm Kiefer, in addition to shows on architecture and design, and the acclaimed Emerging Curators Project. The PSA building hasn’t just marked the city’s landscape with its iconic silhouette, but has served as a witness to Shanghai’s vast changes and transformations.

On the occasion of PSA’s 10th year, Artnet News invited art critic and curator Shen Qilan to conduct an exclusive interview with Gong Yan, the museum’s director. In the following conversation, Gong opens up about her decade-long work at the museum, where she established its curatorial direction, refined its visual identity, and formed its global connections.

Power Station of Art on the bank of Huangpu River. Photo: ©PSA

When PSA opened 10 years ago as the first state-owned contemporary art museum in China, did it draw from the models of other institutions? What kind of museum did PSA want to be?

We did not model any particular institution at the time. I joined the project at the end of 2011 when we were working as a preparatory team. One of my tasks was to establish overseas connections and tell the world about Shanghai’s visions.

The city officials wanted to use the Paris and London models as reference and I thought, since we were looking at Paris as a model, we should invite Centre Pompidou. After the first meeting with the director of Pompidou, they were initially quite surprised and even skeptical—could Shanghai realize this? Centre Pompidou sent a delegation to visit our site.

I suggested exhibiting the Surrealist works from the Pompidou collection because Surrealism is the stepping stone for contemporary art. What’s more, I felt that Surrealist works were in tune with the vibe of the city at the time. How would the area respond to the sudden arrival of contemporary art? It felt quite magical and surreal.

The Surrealist works enjoy a platinum status in the Pompidou collection; reflecting the essence of Zeitgeist. They agreed and proposed a list of works. But when I received the list, I felt it was not what I expected.

Why?

I told the curator that they were not giving us the most important works. The loan list went through several versions; when I finally saw the “reluctance” in their curator’s eyes, the stone in my heart was finally put down. We received the most significant and magnificent Surrealist works for the show, such as Duchamp’s bottle rack and valises, as well as works by Ernst, Miró, and a huge piece by Stella.

The whole process was exciting and I think the curator of Pompidou found it very interesting as well. That year, he was also thinking of doing a Surrealist exhibition himself, so he used this opportunity in Shanghai as a trial. Two years later, he launched a big Surrealist exhibition at Centre Pompidou; most of the exhibits were the same as the Shanghai exhibition.

What were your first actions when you were appointed museum director in 2013?

Starting with our look. Our museum is probably the earliest institution in China to develop a complete system of signage. The museum signage system should speak for itself—it reflects the five basic elements needed for an art museum through the variations of the five bars in the “Dang” character. It had to be simple and easy to remember, and it is better to have a sense of humor by looking like a big chimney visually.

Another important thing was to give the museum an English name—Power Station of Art. We were hesitant if the word “power” would be too strong. Boris Groys, a museum friend, said that an artist or institution should be ambitious like that. I feel that it’s also a kind of manifesto.

Installation view of “Bâton Serpent III Spur Track To The Left,” 2016 at Power Station of Art.

In your dealings with the international art community over the past 10 years, have these boundaries changed much?

I feel that the change has been significant: from 2012 or 2013 to now, there has been a dramatic change in the perception of China by international institutions. This is not something that can be done by a contemporary art museum alone. Whether institutional galleries or individual artists, including art schools—they all want to make their voices heard in Shanghai. Shanghai is willing to embrace contemporary culture in order to match other international cosmopolises. If a cosmopolis is always about finance, politics, economics, and trade, that would be deficient and cannot be truly respected. Ultimately, what people respect and aspire to is culture, and Paris and London are the best examples.

How does PSA choose what kind of exhibitions to host or which artists to show? What are the criteria for this judgment? For example, Liang Shaoji’s exhibition could not have happened anywhere else.

There are both subjective and objective elements to it. If you are completely objective, open an art history book and make your pick. The reason that I went from artist to working in art media to running an institution is that, when I see peers that are more talented or the older generation of artists being neglected and forgotten by the times, I feel pity. Discovering great artists gives me tremendous joy.

Whether it is Liang Shaoji, or the exhibition of Xia Yang and Ding Liren that we just did in December, I think their exceptionally vigorous and unique creativity and inventiveness should be seen by more young people. It is not their age but their artistic attitude that should be rescued. What we want to salvage is the creative ability that is slowly being lost in the booming art market.

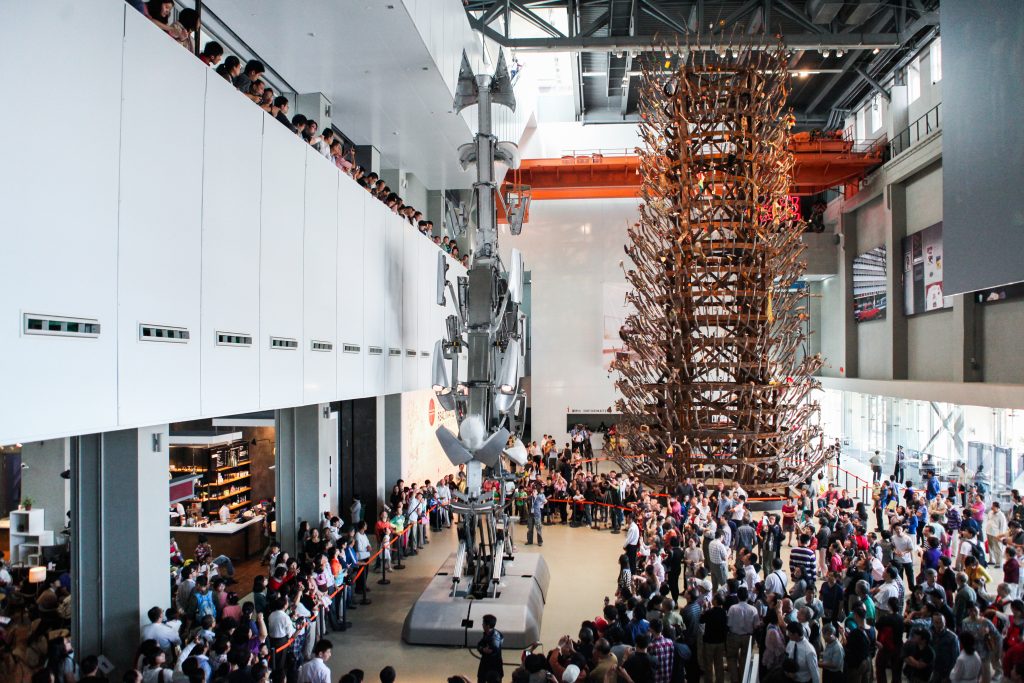

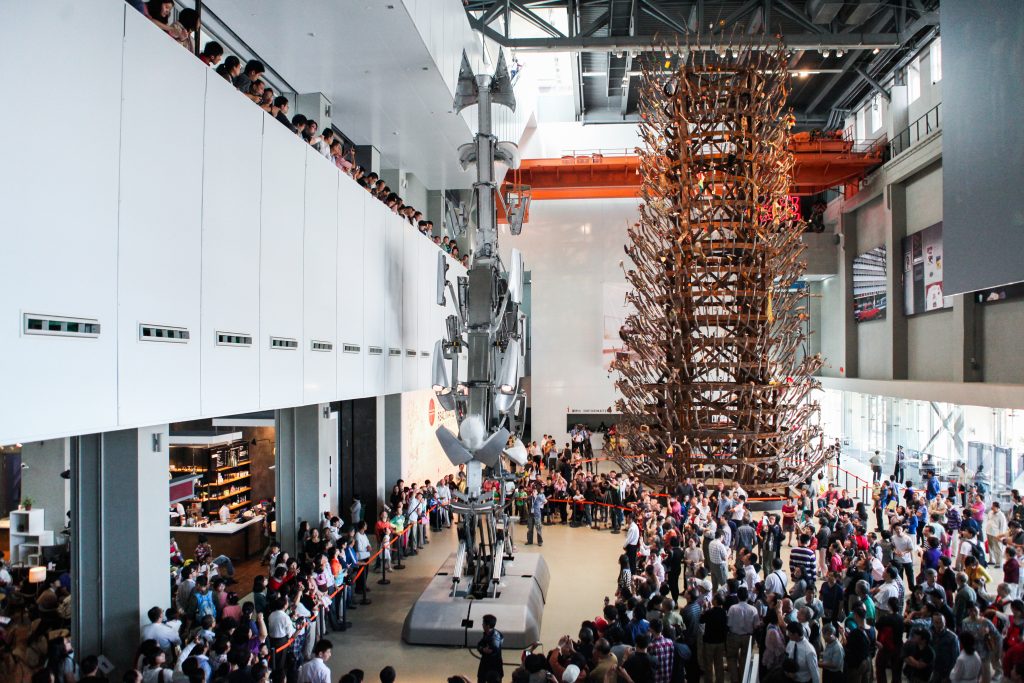

Installation view of the 9th Shanghai Biennale, 2012, Power Station of Art

Let’s talk about the Shanghai Biennale. The previous editions “Why Not Ask Again,” “Social Factory,” “Proregress,” and “Bodies of Water” were all curated by foreign curators. Going forward, how will the Shanghai Biennale proceed?

In 2014, we changed the curatorial selection system; previously it was basically a system of a balancing act, that is, one Chinese curator collaborating with a foreigner, which sometimes felt like contrived matchmaking. Since 2014, we have adopted the “lead curator” system regardless of nationality; the only hope is that the lead curator can fully fulfill his or her curatorial vision. As long as his or her proposal shows sufficient necessity and urgency, and he or she is someone who has good artistic perceptiveness and can communicate with artists and live with them, we will conduct in-depth communications, before putting it to a vote by the academic committee.

How would you respond if an exhibition or work causes controversy? What position does the museum take when an artist is criticized?

There is definitely criticism. I think a lot of criticism stems from a lack of communication. Communication is to seek common ground while acknowledging differences. At least we have to have a dialogue; if there is no exchange of views, [the criticism] is mere conjecture.

For example, some of Li Shan’s works challenge certain traditional ethics, but he has spent 20 years getting ready to reply to those ethical taboos with his life. If not in a public space like the museum, he may not have the opportunity to face the general public’s perception and to have an open and meaningful discussion in the public sphere.

The only time I was outraged was when one of the press reviewed the Datong Dazhang exhibition. The press called it “negative.” I couldn’t understand what they meant by “negative.” Doesn’t a person have the right to decide his own life and death? Such a shallow and rude understanding of humanity is intolerable. Art should defend humanity and protect the basic right to exist as an individual.

Li Shan, Smear-1 (2017). Photo: PSA Collection Series – Li Shan

How do you think the interest of foreign art institutions in Chinese contemporary art has changed?

I think we have not done enough in this regard. In the early years, we mostly “imported.” One thing we can see is that international artists are very interested in showing in Shanghai, and they are very much looking forward to it.

The number of curators in China is indeed rising, which has formed a healthier and more positive understanding of curation; curators today are very capable of communicating, and language is no longer a barrier. Foreign artists and institutions trust Chinese curators to curate shows of foreign artists in the hope of getting a different perspective, which I think is a good thing.

However, it is true that we have taken too little initiative in taking Chinese artists overseas, which is actually very important work going forward; the only traveling exhibition we did was to take Yona Friedman’s show to Rome.

What do you think about touring international exhibitions?

I think it’s judged by impact and significance. Collaboration is actually an opportunity to learn and show how much you can do. Otherwise, it’s just cultural commerce.

We need to build something together upon a shared sense of challenge and urgency in our international engagements. For example, during the collaboration with Centre Pompidou in 2012, we put a lot of pressure on the curatorial process and with each kind reminder people would realize that you were serious, and then they would devote more. I think this kind of friendship is solid, and because of such respect, discussions from an academic angle can ensue. This is true equality, which is not just a word on paper. Cooperation leads to future co-creation.

I think we also have to be selective in emulating others. What we must learn from foreign institutions is their rich cultural legacy, but the richness should be carried by not heavy footsteps. Any institution, having reached a certain level of development, will inevitably show its limitations; when it has become a huge machine, it would be difficult to dance.

Opening Ceremony of The Challenging Souls Yves Klein, Lee Ufan, Ding Yi, 2019, Power Station of Art

Do you have any dream projects at the moment?

We want to build a library. It has been five years, but there is no funding yet. We hope to have a library of contemporary art, as well as an archive, which can be used by scholars for archival research. We have a lot of artists’ manuscripts, letters, and other precious materials. We hope that support from the public sector will come together to do this.

In the future, I want to renovate the chimney. We will have a chimney museum, but I cannot disclose specific plans yet.

This interview was originally conducted in Chinese and translated by Leo Yuan.

Shen Qilan is an art critic, curator, writer and cultural scholar. She holds a Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Münster, Germany. Formerly the editorial director of Art World magazine in China, she has curated exhibitions, conceived programs, and written catalogue essays for international museums and foundations, including the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney; Uffizi Museum, Florence; and Long Museum, Shanghai, among many others.