Today, hand axes are considered foundational artifacts for understanding prehistoric humans. But prior to the Enlightenment and the emergence of paleontology, what did they signify to the people who found and preserved them?

This is an intriguing, yet unresolved, question posed in a new research paper by academics from Dartmouth College and the University of Cambridge that examines a stone object that resembles a hand axe and appears in the Melun Diptych, a c. 1455 painting by the Northern Renaissance artist Jean Fouquet.

Jean Fouquet, Virgin and Child Surrounded by Angels, the right panel of the Melun Diptych (circa 1455). © Antwerpen, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten.

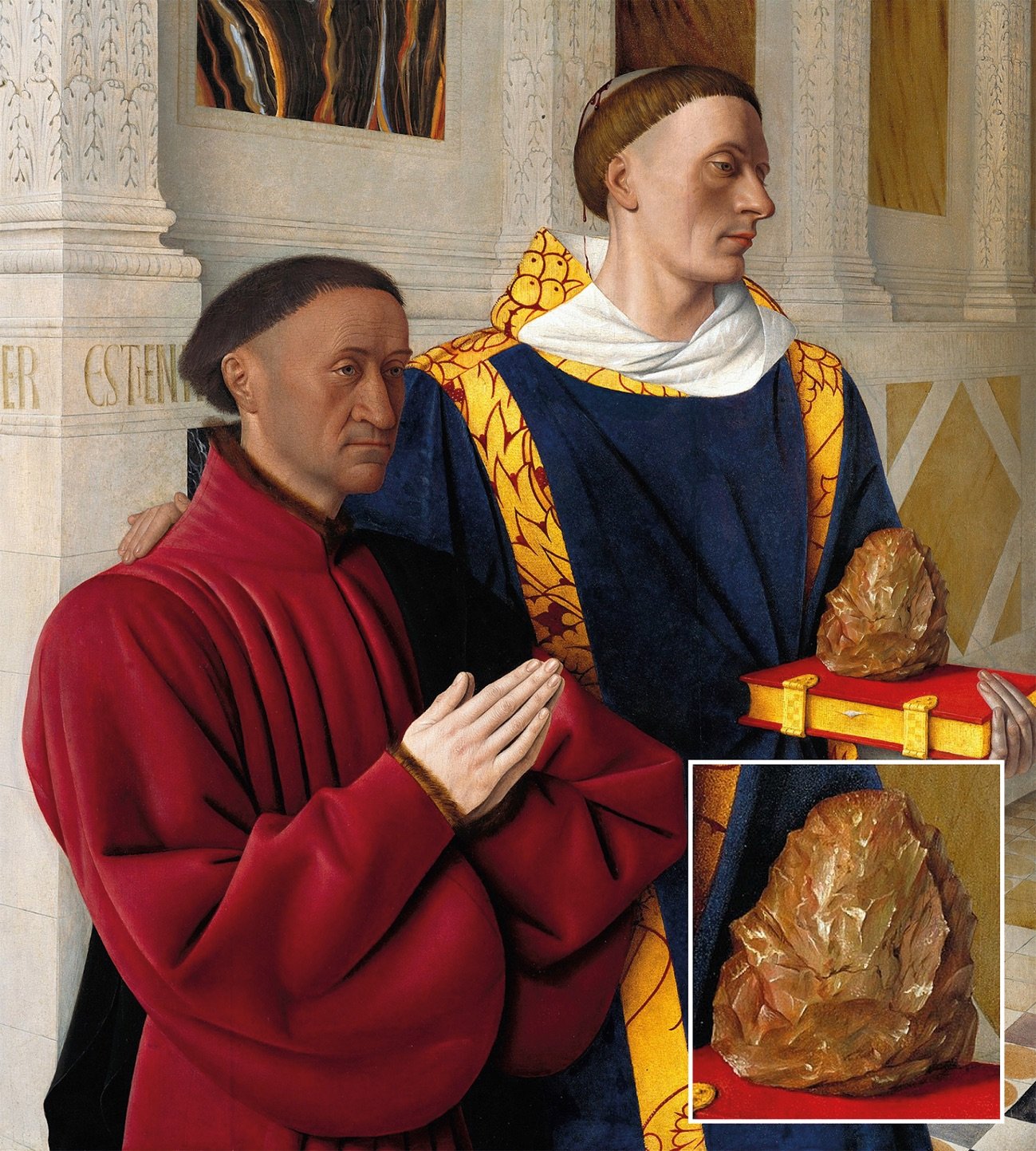

The Melun Diptych takes its name from the Northern French town in which church the painting was originally housed. The right panel depicts an enthroned Virgin with Child surrounded by blue and red cherubs. The left panel shows the diptych’s commissioner, Étienne Chevalier, kneeling beside his patron saint St. Steven, who holds a gilded book upon which the stone in question sits.

The object has traditionally been understood simply as a reference to St. Steven’s martyrdom by stoning. The article published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal suggests the meticulous detail with which Fouquet painted the stone turns it into a “sacred relic,” one that likely had social or religious functions in 15th-century France.

“The hand axe–like stone had social significance and the painting now adds to our already complex understanding of the social implications of hand axes across Paleolithic, historic, and modern periods,” the authors wrote.

The stone object placed alongside the raw outline coordinates and other artifacts used in the paper’s analysis. Courtesy Steven Kangas and authors.

The paper notes that the society in which Fouquet lived had uncovered flint tools, known as Acheulean handaxes, in regional quarries. Indeed, there is written record of people in Europe finding such objects in the mid-1500s, though at the time they were believed to be “thunderstones shot down from the heavens.” This paper strongly suggests prehistoric hand axes were discovered and cherished more than a century earlier than was previously known.

To identify the hand axe, researchers compared Fouquet’s painted stone with those discovered in Northern Europe and focused on shape, color, and the number of cut flake marks.

“This interpretation is supported by our shape and flake scar analyses, which demonstrate the object to be typical for European Acheulean assemblages,” the researchers wrote.

The possible presence of a prehistoric tool in the Fouquet painting had preoccupied Steven Kangas, a Dartmouth College art history professor, for years. After attending a lecture on Tanzanian hand axes, Kangas connected a paleoanthropologist colleague and two Cambridge scholars and began researching.

Their conclusions on the Melun Diptych suggest the need for more research into the importance of prehistoric hand axes in the pre-Enlightenment world.