People

‘Hysteria Is Still Taboo’: Performance Art Dynamo Nora Turato on Why the Art World Still Isn’t Ready to Hear a Woman Scream

The Croatia-born, Amsterdam-based artist is on a hot streak.

The Croatia-born, Amsterdam-based artist is on a hot streak.

Kate Brown

She performs in the typically quiet, hallowed halls of museums, galleries, and even churches. She storms around; she gets hysterical.

Nora Turato’s penchant for disruption has earned her, at 27 years old, a coveted place in the European art scene. Although she comes from a somewhat unexpected background—she found her way to art via punk music and graphic design—the Croatian-born, Amsterdam-based talent has rapidly assembled an impressive resume that includes a performance at Manifesta in Palermo and a buzzy turn at the Liste art fair in Basel this past summer. Both left onlookers a bit bewildered.

Now, she’s working on two solo shows that open in early 2019, one at arts center Beursschouwburg in Brussels and the other at the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein. Last week, she wrapped up her two-year stay at the prestigious Rijksakademie residency in the Dutch capital.

This rapid-fire pace is fitting for an artist whose work is as dynamic as Turato’s. Typically setting herself up against a backdrop of dizzying text-based posters or typographic videos, Turato presents brazen, wandering monologues using her most transgressive artistic tool: her voice.

Nora Turato, i’m happy to own my implicit biases, 2018, performed at Oratorio San Lorenzo, Palermo, as part of Manifesta 12. Courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina; Photo credit: Francesco Bellina

“Rarely do you see artworks where the female voice is going to these extremes,” Turato tells artnet News from her home in Amsterdam. “It’s usually trying to be sexy, calm—like a voice operator. And rarely do you see the female voice being used hysterically.” (“Sorry… I just ramble,” says Turato to an audience after spewing a bunch of sounds in her recent performance leaning is the new sitting at Vleeshal Markt in Holland. “I often say ‘sorry’ when I mean ‘thank you,'” she continues. “But I was only given a nail file and ‘sorry’ to cut my way out.”)

Turato enters into typically male-dominated spaces in an armor of conspicuous, colorful garb—like a tailored Balenciaga suit paired with spiked heels. And she starts talking. She goes on for half an hour (right around the length of a punk record) and, with her clipped melodies, she races through a stream-of-consciousness tangle of references that range from advertisements to book excerpts, movie quotes, and social-media posts. As artnet News’s editor-in-chief Andrew Goldstein described it, “the effect is a bit like listening to ‘The Wasteland’ as composed by a bot and broadcast via Alexa.”

Nora Turato, i’m happy to own my implicit biases, 2018, performed at Fffriedrich, Frankfurt; Courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina; Photo credit: Eike Walkenhorst

Croatia’s bloody war of independence broke out in 1991, the same year the 27-year-old artist was born. Luckily, she says, her family was not directly involved, so her trauma is much milder than that of many others from her generation. But, nevertheless, she came of age in the context of Croatia’s hardened postwar and post-socialist music scene emboldened. After high school, she moved to Amsterdam to study graphic design at one of the city’s top art schools, the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, and took up work as a full-time graphic designer.

Condo New York, LambdaLambdaLambda at Metro Pictures, New York, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina; Photo credit: Object Studies

Turato says she was always performing on the side. “I never became an artist on purpose,” Turato says. “I’m doing this by accident because the art world was the first world that let me do this.”

It’s true that her work could just as easily be adapted to cinema, avant-garde theater, or fold back into music. But after a long spell as a musician in Croatia, she found the punk scene boys’ club boring; the Dutch art world proved to be more engaging and accepting. “There’s still a genuine surprise when women do something good in music,” she says.

And like many immigrants, she now feels at home both everywhere and nowhere. “I had to change my ways a lot to exist in Holland,” she recalls. “There is something about living in the West and having a distance from it. But I also have distance from back home. I am always somewhere in between.”

The spoken word artist explores the feeling of not-quite-belonging in her performances. At Kunstverein Bielefeld in Germany earlier this fall, Turato pounded around the institution in a cobalt blue suit jacket and a vibrant orange turtle neck that matched her dyed hair, frantically listing off the things her peers have obsolesced while she glared back fiercely into a crowd that quietly lined the walls.

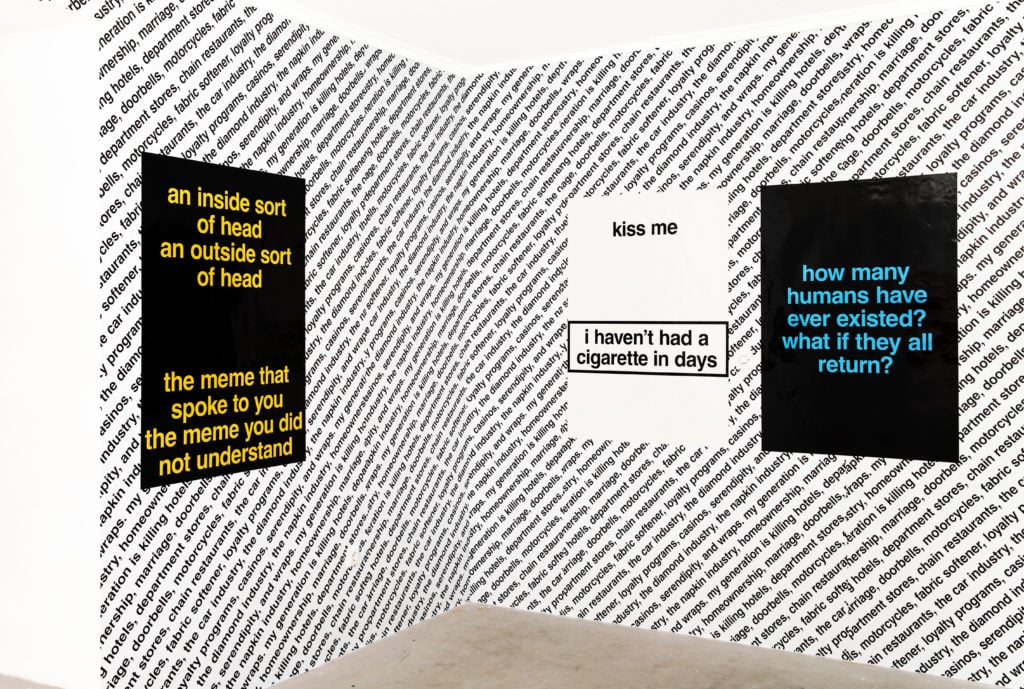

“My generation… My generation is killing hotels, department stores, chain restaurants, the car industry, diamond industry, napkin industry, home ownership, marriage, doorbells…serendipity…” She speeds up; her list goes on. With raucous acceleration, you can almost feel the BPMs turning up—changing a tangent into a punk anthem that’s too frank to be cynical.

Nora Turato, i’m happy to own my implicit biases, 2018, performed at Oratorio San Lorenzo, Palermo, as part of Manifesta 12. Courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina; Photo credit: Francesco Bellina

Turato’s experience in advertising is evident in her magnetic, bold, sans serif posters, which bear snappy slogans reminiscent of advertising billboards. She prefers the simplicity of print because it recalls inexpensive merch seen at music venues. She doesn’t want to make art that’s too precious.

But while her ephemera aims to look both casual and replicable, her presence is anything but that. “I wondered what could come next after this whole ‘don’t-give-a-fuck’ moment,” she says, reflecting on the abject trend in contemporary art that surrounded her. That’s partly why she decided it was important for her to dress well.

Her formalism in dress stands in stark contrast to other performance artists of the moment, who opt rather for more unstudied or so-called effortlessness fashion. (Anne Imhof’s Golden Lion-winning performance at the Venice Biennale in 2017, for example, included performers that were meticulously dressed to look like they had just rolled out of bed.) “I do give a fuck, so what do I wear if I really do give a fuck?” asks Turato.

Nora Turato, A Festival of Consent (2018). Installation view, LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina. Courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina. Photo credit: Lule Bagta.

As she steps into character, Turato describes going into “complete autopilot.” (She memorizes her lengthy scripts beforehand.) “If I was doing what I do in Croatia, I would be seen as nothing short of insane,” she points out. “I don’t think Croatia would be ready to have a woman talk like this yet.”

Depending on the mood and composition of the audience—the more men present, the more skeptically she says she is received—Turato reworks her lines each time, ramping up particular snippets. “It’s like a band performing their favorite song,” she says. Lines are repeated like a hit chorus, but a little differently every time.

Her work can still be a tough pill for audiences to swallow. At Manifesta 12 this summer, Turato was taken aback by the audience’s reaction to her performance at a baroque chapel in Palermo during the opening days of the nomadic European biennial. Some people left vicious comments in the book at the front of the church, writing that she was a “crow in paradise” and a witch. “It reminded me of south Croatia, where it is really conservative and Catholic and uptight,” she says.

Nora Turato, i’m happy to own my implicit biases, 2018, performed at Fffriedrich, Frankfurt; Courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina; Photo credit: Eike Walkenhorst

Turato is showing us that, even today and even in the more progressive corners of the world, many are not quite ready to have a woman shriek, rant, gossip, and whine at them, or stare them down. She wryly notes how many words there are to negatively describe a woman’s voice when it does not fall into the soft-spoken category. “I feel like men are still not capable of listening to a woman for 25 minutes straight without saying anything,” she says. “Hysteria is still taboo—no one wants to be seen as hysterical. You do so much by just doing that.”