Even the most radical, anarchic movements of their day are eventually canonized by institutional powers, all while their contemporary equivalents continue to be forcefully crushed. Perhaps it is no surprise then to see archival documentation of early performances by the Russian punk feminist collective Pussy Riot appearing in a museum context. The group caught the world’s attention in 2012, after a guerrilla concert performed in trademark colorful balaclavas outside a cathedral in Moscow landed two of its members in prison.

One of these was co-founder Nadya Tolokonnikova, whose first solo museum exhibition, “RAGE,” opened in June at OK Center for Contemporary Art in Linz, Austria. While it surveys much of her career and Pussy Riot’s work, it is also a showcase for several much newer pieces of activism made in direct response to Russia’s ongoing war on Ukraine and other international injustices, like the U.S. Supreme Court’s attack on women’s reproductive rights.

“It’s very unusual for a museum to not try to censor the political content of art but actually encourage it,” Tolokonnikova said. “I’ve had a lot of private conversations with representatives for various [Western] institutions and they told me they support my mission but, unfortunately, it’s not for them.” Instead, in 2023, she premiered the performance piece Putin’s Ashes at Jeffrey Deitch’s commercial gallery in L.A., one of the few spaces willing to allow her to present new works and performances. As part of the performance, she burned images of the Russian leader. This summer, the Brooklyn Museum acquired Putin’s Ashes for its permanent collection.

Pussy Riot cover of Time Magazine from 2012. Image courtesy of OK Linz.

For a punk protestor, who was imprisoned for almost two years for “hooliganism,” Tolokonnikova is disarmingly soft-spoken. When we met in the lobby of her London hotel, she wore a timeless gothic outfit complete with black boots, black nails, tattoos, fishnets, and heavy eyeliner. In discussing her past, she appears startlingly unfazed when making frequent passing reference to traumatic events.

Born in 1989 in the remote Arctic Circle city of Norilsk, Tolokonnikova moved to Moscow at the age of 17 and immediately became involved in performance art as co-founder of the collective Voina. Its name translates to war, meaning, “a war against conservative art institutions and the politics in Russia.” Pussy Riot, an amorphous and international group that anyone is free to join, followed in 2011. Those now seem like halcyon days, as the collective’s work has only grown more urgent.

In early 2021, for example, Pussy Riot joined nationwide protests against the imprisonment of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, a friend of Tolokonnikova’s who died in prison under disputed circumstances in February. He is commemorated by a memorial at OK Linz under a large protest banner reading “murderers.” The filming of RAGE, a performance from 2021 in support of all political prisoners in Russia, was shut down by authorities who accused it of “gay propaganda.” The incident was caught on camera and makes for a fitting conclusion to the work.

Given the constant threat of persecution, Tolokonnikova said preparing for Pussy Riot performances is like a “military bootcamp” that includes learning self-defense tactics and keeping very fit. “The idea of Pussy Riot is that we are almost a superhero-type force that cannot be tackled by something as mundane as the police,” she said.

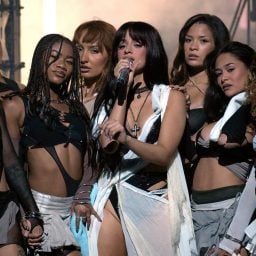

Performance by Pussy Riot at OK Linz in June 2024. Photo: molly.a.pop.

The institutional setting of OK Linz is worlds away from these working conditions. “It wasn’t extremely difficult to put together a show when you don’t have police trying to drag you away,” Tolokonnikova shrugged with a wry laugh. But, she stressed, the presence of her work in an institution by no means amounts to its fossilization. These performances live on through their documentation and the nature of this afterlife becomes part of the work.

“Our goal is to involve people,” she said, which includes “the reaction of people who watch the video, whether they’re enraged and want to burn us at the stake or are inspired. Performance art removes the fourth wall.”

On the opening night of “RAGE” on June 20, Tolokonnikova staged a new performance. Wearing a yellow balaclava, she sang with raspy, tortured vocals while standing beneath a giant, suspended knife titled Damokles Sword, which she modeled on a prison shiv. It is hardly an ambiguous metaphor for the danger that hangs over Tolokonnikova’s head at all times since Russia added her to its list of wanted “foreign agents” in 2021.

Another live performance, also titled RAGE and featuring 50 members of Pussy Riot, will take place on July 4 at 8:15 p.m. at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin.

Installation view of Rage Chapel at “RAGE” exhibition at OK Linz in Austria. Photo: Manuel Carreon Lopez.

In translating her earlier oeuvre into the Western institutional context, Tolokonnikova was inspired by the late Ilya Kabakov. After emigrating to the U.S., he made immersive environments known as “total installations” so that he could “put people inside the world that was stolen from him by his government.”

As this reference might suggest, Tolokonnikova’s anti-Putin stance is born of a deep love for her country. She expressed pride in many aspects of Slavic history, from Malevich’s Black Square—“they wanted to change the old world and build a new one”—to the Russian Religious Renaissance, an important philosophical movement that was exiled by the Bolsheviks. Tolokonnikova’s resistance is a part of this legacy, a way for her to uphold rather than deny what she sees as essentially Russian values.

The first room of “RAGE,” known as the Rage Chapel, is dedicated to Russian activists and inspired by advice from Tolokonnikova’s father that “a good artist is one who creates their own religion.” It contains a series of icons in the manner of the Orthodox tradition, including gold-leafed portraits of anonymous Pussy Riot members bearing slogans like “fear no more”—a phrase borrowed from Navalny—and “enlightening of the darkness.” On the opposite wall is a riot symbol that vaguely resembles the Christian cross and bathes the room in its warm red glow.

Installation view of Putin’s Mausoleum at “RAGE” exhibition at OK Linz in Austria. Photo: Manuel Carreon Lopez.

In the next room, Putin’s Mausoleum, Tolokonnikova has screened the performance of Putin’s Ashes. The ashes of the president’s photos that she burned are displayed nearby in labeled glass vials. It marks one of her first uses of the physical object as a documentation device, which she compares to “a relic or a monument.”

One of the show’s focal points is a life-size replica of Tolokonnikova’s prison cell at the penal colony in Mordovia, where she was detained for 22 months between 2012 and 2013. The durational work of Marina Abramović has helped Tolokonnikova make sense of this period in her early twenties.

“To claim this time back and not let the Russian government own two years of my life, I say it was my performance,” she explained.

Tolokonnikova pictured in the replica of her prison cell at OK Linz. Photo: Manuel Carreon Lopez.

Tolokonnikova has recently been embraced by many figures in the international art community, including Abramović, Jenny Holzer, the Guerrilla Girls, and Judy Chicago. However, “I never wanted to be a nomad,” she said of her itinerant existence. “When you live in exile it is so difficult to continue making good art. It’s so important to be close to your context.”

Nonetheless, it is clear that whatever challenges the world puts forward, Pussy Riot will rise to meet them. Last November, the group stormed the Indiana Supreme Court in a performance titled “God Save Abortion.”

“In 2011, when we started Pussy Riot, it was really a time of hope,” said Tolokonnikova, referring to anti-Putin uprisings across Russia. That year also saw the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street movement. “Since then, everything has become worse and worse but I don’t want to give up on hope. My role in life is very simple. My goal is to always think about the future.”

“RAGE: Nadya Tolokonnikova Pussy Riot” is on view at OK Linz through October 20, 2024.