Art World

Q & A with Artist Martha Rosler

Photomontage artist Martha Rosler's exhibition is at the Bronx Museum.

Photomontage artist Martha Rosler's exhibition is at the Bronx Museum.

Bree Hughes

We interview artist Martha Rosler, whose work is currently on view through September 8 in the exhibition, State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970, at the Bronx Museum in New York, NY.

Bree Hughes: How has your work changed the past 20 years? How has your audience changed?

Martha Rosler: I use more digital imagery than I used to, and I am more likely to orchestrate events with a number of participants, but those are largely technical issues, I think. Otherwise, I am not sure the basic impulses of my work have changed much. My audience has no doubt broadened as the art audience has expanded and internationalized, as time has passed, and as the internet has become the primary means of disseminating imagery and commentary. In the case of anti-war photomontages, I have consciously chosen, in effect, to quote my own method of work from forty years previously in order to create a meta-level commentary about the failure of our political class to learn anything from history. Today, we have new wars of choice that are being waged with the old mindset, so I chose to use the same mode of address: the photomontage.

Martha Rosler, Playboy (On View) from Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful, 1967–1972

BH: Most of your early work is about women in the domestic space. Is your message still about the domestic space and women?

MR: Even in the beginning, you could not make such generalizations about my work, since I was in fact a painter and part-time documentary photographer. But I will grant you that a lot of my work between the mid-1960s through the mid-1970s overtly addressed women and their representations. Although that is not always the first thing you see when you look at my work, I maintain that all my work is feminist, in that it insists on returning our attention to the social context of the work’s production and reception.

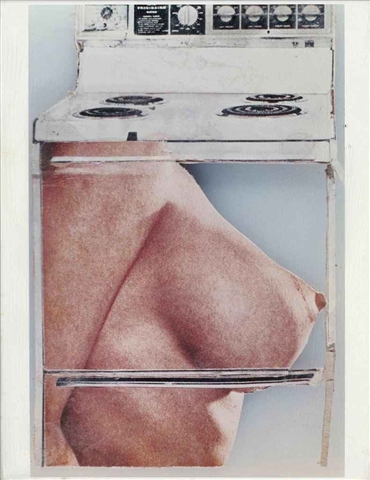

Martha Rosler, Hot Meat, from Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain, c.1966–1972

BH: What are your thoughts on the recent statistics that female breadwinners are on the rise? How do you think this affects home life?

MR: The present state of our economy, which has been characterized as a knowledge economy in a deterrorialized world, has no justification for discriminating against people on the basis of identity; the skills of the knowledge economy can be manifested by people with just about any identity (although prejudice has not been eradicated). Simultaneously, working-class jobs in goods production, and increasingly in service, have been outsourced, leading to what’s been called a “race to the bottom,” in which wages here at home are stagnant or falling, making it necessary for more than one person to support a family. Women are still cheaper than men, and thus in our prolonged economic crisis: higher-earning men are fired first, leaving more women as economic heads-of-households. At the same time, women’s ability to earn a wage means that they do not need to get married to ensure economic security.

BH: How is the preparation for a garage sale project different from a video project? How long are your timelines?

MR: An event like a garage sale requires long preparation time in terms of strategizing performance elements and staging the design, and construction of the space, the preparation and assembly of exhibition elements, and the accumulation and processing of goods. I remarked to the MoMA curator who commissioned me that, like Napoleon invading Russia, we were doomed to fail without adequate preparation, including our matériel–equipment and supply–trains set up well in advance. We took a year and a half to get the show underway.

Video projects on the other hand vary widely in what kind of work they require. Some are highly scripted and require actors, locations, and rehearsals, while others are essentially improv, and yet others are heavily dependent on editing. Some are very simple and are quick to work on. Some are constructed in the computer. Some require me or someone else to shoot footage, and others require me to assemble found material. I have made videos that required weeks and months of preparation and others were done almost on the spur of the moment.

For my sculptural and photographic projects, the former tend to be based on an idea that I then carry through, sometimes with little direct research, but photographic projects can take years and years to come to fruition.

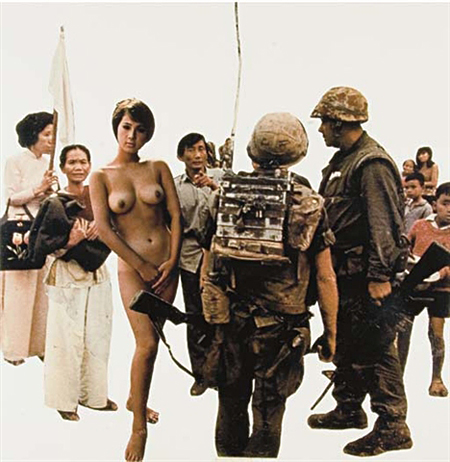

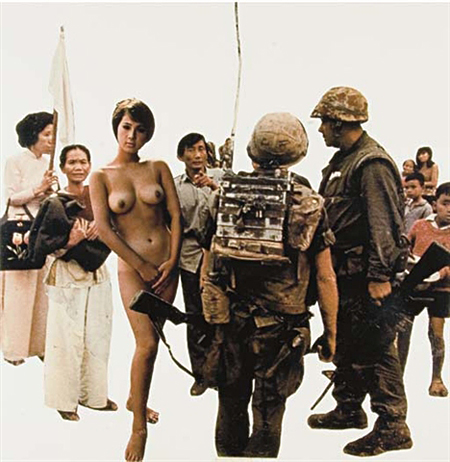

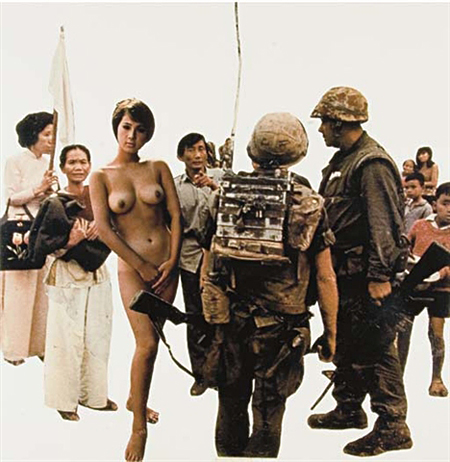

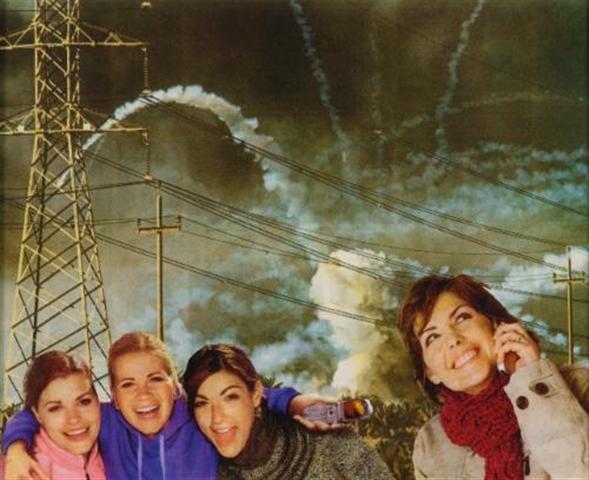

Martha Rosler, Cellular, from Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful, 2004

BH: What are you trying to communicate with your art?

MR: I want to open a space in people’s minds where they see that they can be active, intellectually and personally, rather than passive recipients of received ideas and prevailing worldviews. It is not answers I hope to provide but questions, questions for people to take home and think about.

BH: Would you recommend any particular type of training to people interested in becoming performance artists?

MR: Performance is a funny undertaking. It is similar to acting but not the same by any means. Most performance artists, especially young women, rely on what is essentially self-expression, activating a rather romantic and even old-fashioned idea of what that might consist of, and how much one’s rational mind interferes with that process. I think young performance artists ought to work on other people’s performances to break that attachment to the autobiographical, the psychoanalytic, and so on. Working collectively tends to help you curb your ego in the service of your art.

BH: Do you collect art yourself? If so, tell us about your collection.

MR: Like many artists, I collect amateur and thrift-store art, but I also collect women’s and girls’ needlework, especially the most ordinary.