The president of Paris’s Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac has spoken out against a radical report advising the French President, Emmanuel Macron, on the return of African art plundered during the colonial period.

The first senior French museum official to criticize the report in public, Stéphane Martin told AFP on Tuesday (November 27) that he disagrees with the proposals for a “maximal restitution” set forth by its co-authors, the academics Bénédicte Savoy and Felwine Sarr. Martin argues that a statement from the presidential palace on Friday, November 23, leans more towards the increased circulation of African art in French collections rather than their wholesale return.

The Savoy-Sarr report proposes a progressive and permanent restitution of Sub-Saharan African art acquired “without consent” during the colonial era. Tens of thousands of works in the French national collection are potentially implicated.

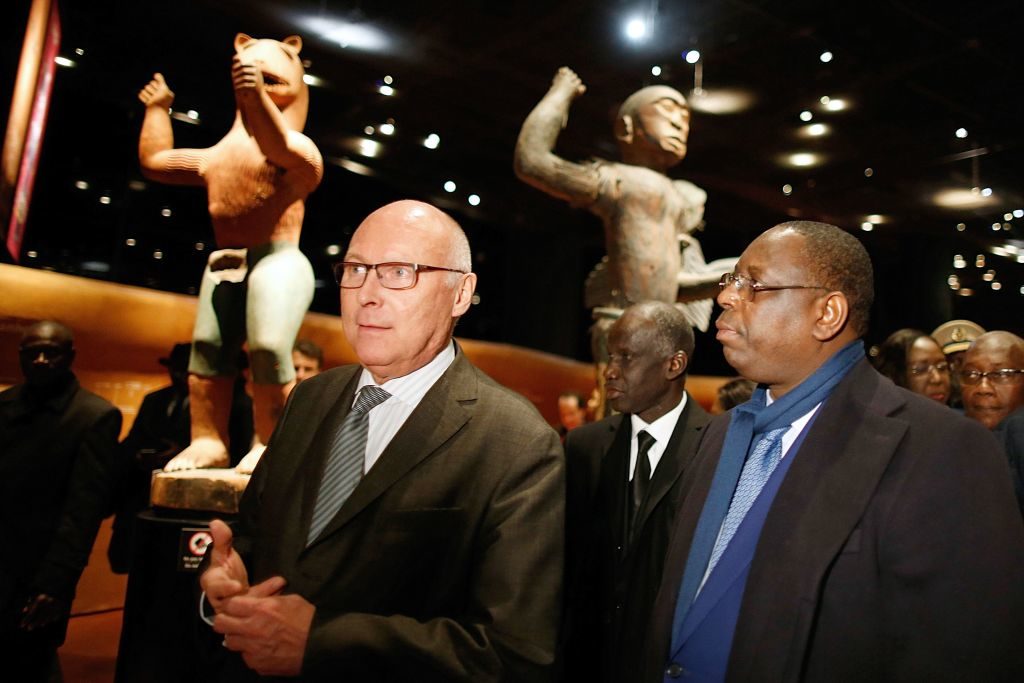

The Musée du Quai Branly, which Martin has lead since 1998, was created to bring together the art and culture of Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas in a new home designed by Jean Nouvel. It holds nearly 80 percent of the works of African art in French public collections, around 70,000 pieces in total.

In a gesture of the seriousness of the French commitment to restituting these objects, the Élysée palace announced that 26 objects from the quai Branly collection will be returned to the kingdom of Benin “without delay.”

Tainted With the Same Brush

Martin says the “main problem” with Savoy and Sarr’s report is that “it sidelines museums in favor of specialists in historical reparations.”

The museum president says he disagrees with the conclusion of the report, which taints all objects acquired during the colonial era with the same brush. It stains “all that was collected and bought during the colonial period” with “the impurity of colonial crime,” he says.

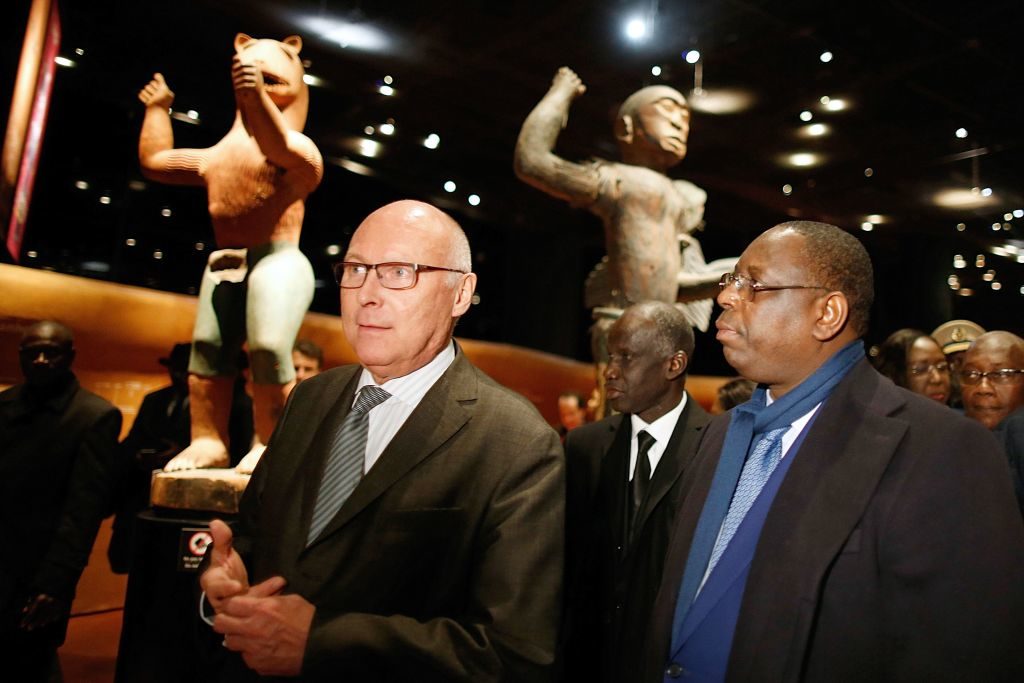

Stéphane Martin (left) and the Senegalese President Macky Sall during a visit to the quai Branly museum in Paris. Photo by Charles Platiau/AFP/Getty Images.

Martin says the report makes vulnerable “donations to museums from people related to colonization (administrators, doctors, soldiers) and their descendants” as well as “everything that was collected by scientific expeditions.” Gifts given freely would also be susceptible to restitution claims, he adds, offering up the example of works in the collection that were gifts from Cameroonian chiefs to a doctor, Pierre Harter, who treated their families for leprosy in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Martin also balked at Savoy and Sarr’s suggestion of establishing a “mixed commission” to deal with each demand for restitution. “It would be a huge overhaul of French law for a foreign state to have equal footing with the French nation in determining what is rightfully or not a part of its own heritage.”

Loans, Not Returns

The museum president does not think the release issued by the Élysée endorses the idea of comprehensive restitution. “The way I read it, it closes the door on the Savoy-Sarr report by insisting that museums, and above all universal museums, are an important element of the common heritage of humanity,” Martin says.

He believes that the French president intends for “circulation” to remain the principal means of cultural diffusion. To support this belief, he cites part of the release stating Macron’s hope that “all possible forms of circulation of these works be considered” including “restitution, but also exhibitions, exchanges, loans, deposits, and cooperation.”

Martin says restitution “can, in very specific cases, be considered,” as in the case of the Benin sculptures exhibited at Quai Branly that were ransacked from the Dahomey king’s palace in 1892 by the French. That said, he maintains that there have long been examples of these transfers of state-to-state ownership. “The Getty has returned objects to Italy, the British Museum to Australia, the Musée Guimet Museum to China,” he says, arguing that the “current legal apparatus” in place is sufficient to organize the deaccessioning of these works.

The Quai Branly Museum-Jacques Chirac. Photo by Ludovic Marin/AFP/Getty Images.

Restitution “cannot be the only way, otherwise we will empty European museums,” Martin says, fearing that “heritage will become the hostage of memory.” Instead, he focuses on alternatives to restitution in which museums can play a role, such as building new museums, and working with private collectors and foundations such as the Zinsou Foundation in Cotonou. Martin says the presidential line “invites museums to play a vital role,” while the report frames museums dismissively as “poachers.” Contacted by artnet News, the Quai Branly did not immediately respond to a request for elaboration on Martin’s comments to AFP.

In all this, France’s new minister for culture Franck Riester, as well as the French minister for foreign affairs, will have an important role to play. Macron has invited heads of state, museum directors, and conservation experts from Africa and Europe to meet in Paris early next year to build on the framework set out in the Savoy-Sarr report.