Art & Exhibitions

Restoration of Famed ‘Rainbow Portrait’ of Queen Elizabeth I Uncovers New Discoveries

The painting, which depicts an ageless monarch, has returned to the Queen's childhood residence at Hatfield House.

The iconic “Rainbow Portrait” of Queen Elizabeth I, painted when she was nearly 70 but where she is portrayed as youthful, has been restored and returned to Hatfield House, which sits alongside her childhood home in Hertfordshire.

“It is probably the most iconic piece in our collections and the focal point of the Marble Hall, so its loss was certainly felt during conservation—the House feels complete once again,” Vannis Jones Rahi, head of archives and collections, told the BBC.

The portrait, painted between 1600 and 1603 by an unknown artist, is believed to be one of the final depictions of Elizabeth I, created just before or shortly after the so-called “Virgin Queen” died in 1603. It has long captured the public imagination. In it, she is seen holding a thin rainbow arc in her right hand, beside which is the Latin inscription, “Non sine sole iris”, or “No rainbow without the sun,” in what is considered a reference to the queen as the sun, both a source of light and wisdom, as well as a harbinger of peace.

After traveling to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Cleveland Museum of Art in 2022 and 2023, the portrait underwent a “meticulous conservation,” by Nicole Ryder, who cleaned and corrected minor losses to the subject matter for more than a year, according to the BBC. The canvas was also X-rayed, and pigments were further analyzed.

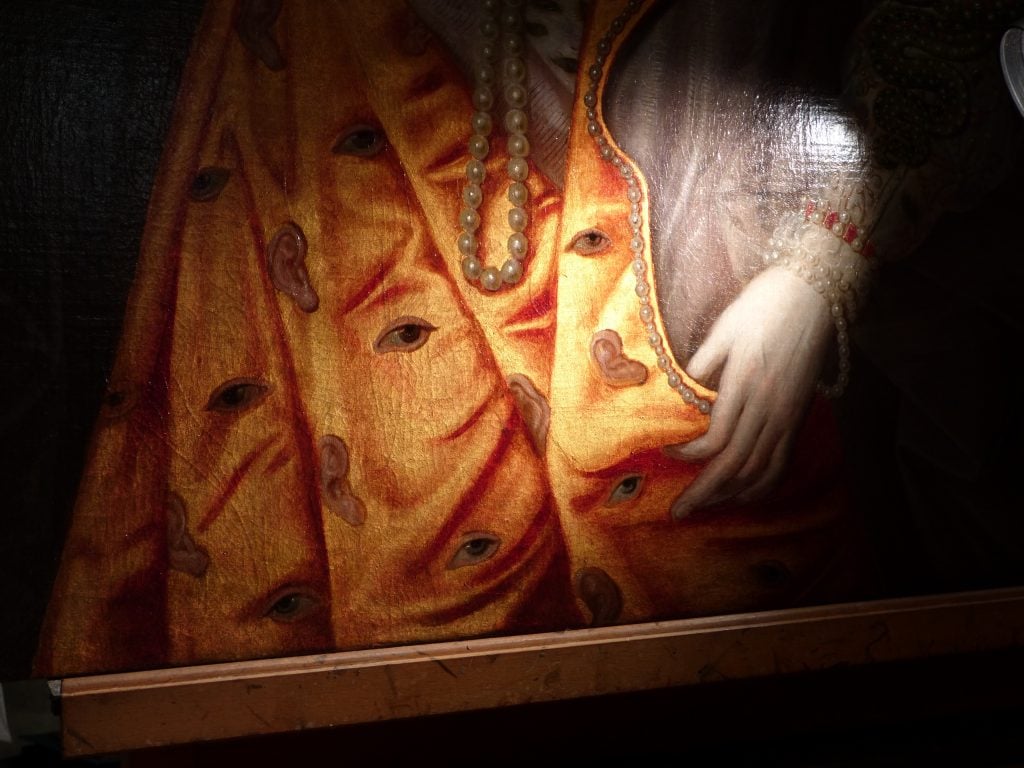

Detail. Rainbow Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I (c. 1600-1603). Courtesy of Hatfield House

The restoration and conservation process also revealed several new discoveries. Most notably, “one of the key takeaways from the event was that all experts were in agreement that this likely represents a posthumous portrait of Elizabeth, rather than one commissioned and painted during her lifetime,” said Rahi in an e-mail. Ryder found underdrawings suggesting the face was created using a pre-existing pattern, so the queen need not have sat for this portrait.

Indeed, instead of depicting an aging monarch, the portraitist took artistic liberties akin to modern-day Photoshop, erasing wrinkles and portraying the queen with ageless beauty. The queen’s thick, blonde, ringlets match a lustrous, golden-tinged, orange cloak. Though she would have been in her 60’s when this was painted, it is believed the queen wanted to be perceived as a youthful, virgin beauty, a message the artist took great pains to convey, down to the smallest details. White pearls, a symbol of chastity, literally drip from her hair, neck, and dress.

The name of the painting’s creator is another great unknown, for which the recent conservation has provided a few more clues. A bill of payment in the Hatfield House Archives from the painter John de Critz for alterations to a portrait of the queen—not unlike alterations revealed during the Rainbow Portrait restoration, “could strengthen the argument for the painting’s attribution to de Critz,” Rahi added. In addition to de Critz, the portrait has been attributed to several other artists, including Federico Zuccaro, Isaac Oliver, Nicholas Hilliard, and Marcus Gheeraerts the Young.

Detail. Rainbow Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I (c. 1600-1603). Courtesy of Hatfield House

Other intriguing, but strange symbols by today’s standards, emerge from the artwork, such as floating eyes and ears on the cloak mentioned, believed to represent Queen Elizabeth’s all-seeing and hearing eyes and ears, as well as her wisdom. A richly embroidered serpent seen on her sleeve was also a recognizable sign of shrewd wisdom in Tudor England.

This early Surrealist cloak, if you will, was originally painted red, not orange, but it had faded, and a layer of 24-carat gold was added, according to Ryder’s study. Its inner lining was also originally purple, not gray, and made from crushed insects. Silver-leaf patterns around her cloak have also disintegrated, and the famous rainbow in the queen’s hand was not painted in shades of gray as it appears now, but full of color.

While scientists now have more clues to work from, questions remain. “This portrait of Elizabeth is enigmatic because there is so much that is still unknown surrounding the painting’s purpose and creation and so much rich symbolism that can be interpreted differently through so many different lenses,” Rahi told reporters.

The portrait’s display in Hatfield House’s Marble Hall, built in 1611, is also a return home of sorts. Elizabeth spent a happy childhood in Hatfield, according to the heritage site. She lived with her siblings in the adjoining Old Palace, a medieval brickwork home built in 1485, of which only the banquet hall remains today. But the princess was also later kept at Hatfield in what amounted to house arrest, after her half-sister, Queen Mary, assumed the throne in 1553, and rightly feared the younger Elizabeth could replace her. As historians tell it, only five years later in 1558, Elizabeth was sitting under an oak tree in Hatfield Park, when she learned she was to become queen. The park’s website points visitors in the direction of that “Elizabeth Oak,” located a good ways off the map.