Art World

‘The Queen’s Gambit’ Has Driven an Unprecedented Surge in Chess Sales. Here Are 13 Classic Artist-Designed Sets to Get Your Fix

From ancient Persian craftsmen to Yoko Ono, artists have reinterpreted the game over the ages.

From ancient Persian craftsmen to Yoko Ono, artists have reinterpreted the game over the ages.

Brian Boucher

The ancient game of chess has everyone abuzz once again, thanks to the enormous popularity of the new show The Queen’s Gambit, in which Anya Taylor-Joy plays a chess prodigy with, well, prodigious issues. Chess sets and books are flying off the shelves as the series rockets to more than 62 million viewers, making it Netflix’s most-watched show ever.

It’s been a long journey for the game, which has traveled from prehistoric origins in India to the Middle East and thence all over the world. It saw a monster wave of popularity in 1972, when America’s Bobby Fischer bested Russian Boris Spassky to win the world championship, which inspired the 1983 novel on which the Netflix show is based.

Among chess’s greatest proponents in the art world was Marcel Duchamp, who even claimed (falsely) to have quit making art in favor of the game (and he did compete at high levels). “From my close contact with artists and chess players,” he said, “I have come to the personal conclusion that while all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists.”

In any event, countless artists have tried their hand at creating chessboards and figures. Here’s a selection of some of our favorite artistic interpretations of the game, starting with examples by anonymous craftsmen of yore and then on to modern interpretations.

Chess set, 12th century, Iran. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

One of the earliest known examples, and an almost complete one to boot, resides at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. The 12th-century Persian who created it may be unknown, but it was certainly an artist by any standard who created these abstract forms.

Unknown artist, China, chess set, 18th century. Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

This stunning ivory set, with detailed figures perched atop elaborate filigreed globes, has resided in an 18th-century period room at the Minneapolis Institute of Art for years. Funnily enough, several years ago, a chess-obsessed visitor pointed out that the setup was anachronistic, with the pieces occupying positions that wouldn’t normally have opened a game at that time, leading the museum to reorganize the pieces into a more historically appropriate gambit.

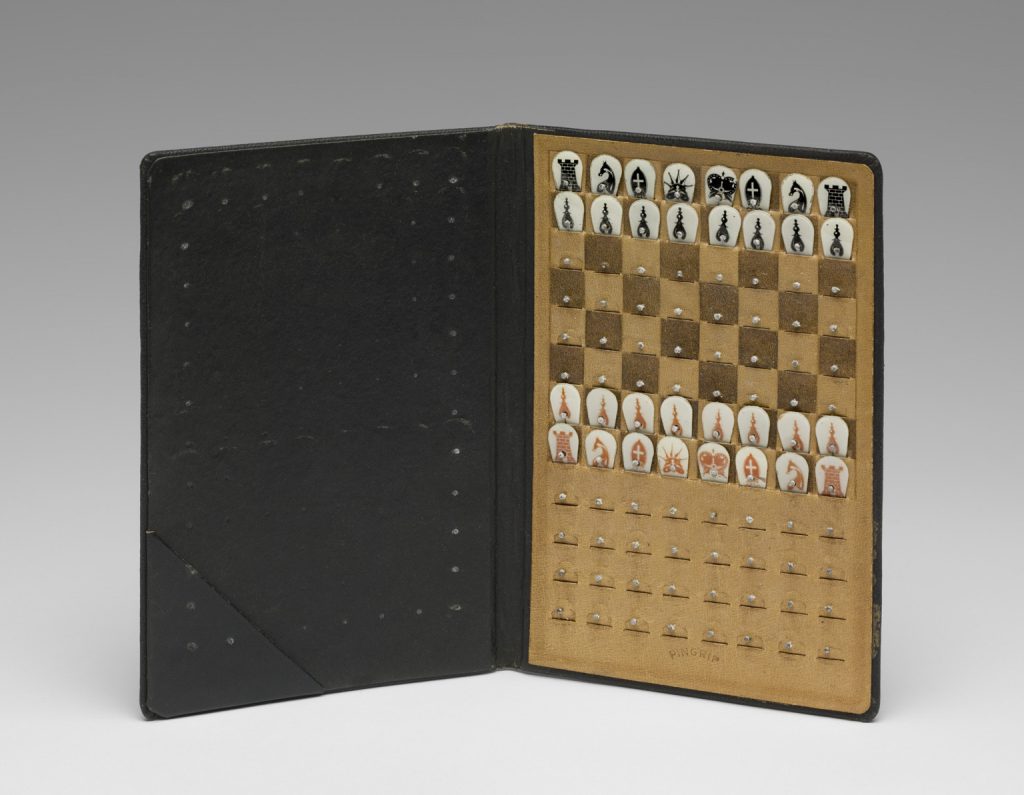

Marcel Duchamp, Pocket Chess Set (1943). © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Succession Marcel Duchamp. The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950. Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2020.

Duchamp created this pocket chess set as a refugee from Europe and, according to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where it resides, planned to produce it in the hundreds, marketing it to players with the guarantee that the pieces would stay in place during travel. It’s akin to his La Boîte-en-valise (Box in a Suitcase), created between 1935 and 1941, a travel case with miniature versions of some of his greatest hits.

Meschac Gaba’s chess set as part of the installation “Game Room” at Tate. Photo by Stefan Rousseau/PA Images via Getty Images.

Back in the 1990s, the Beninese artist Meshac Gaba conceived the Museum of Contemporary African Art as a gambit, if you will, a provocation to the Western art world. One room therein is the Game Room, including a chessboard with one side’s handmade pieces covered in dollar bills and the other’s in euros, suggesting that even allies are in a game of dominance.

Rachel Whiteread, Modern Chess Set. Photo Saul Leob/AFP via Getty Images.

In keeping with her preoccupation with all things domestic and her concern with gender roles, the English artist Rachel Whiteread modeled all the pieces in her Modern Chess Set on objects from her personal collection of dollhouses.

Maurizio Cattelan, Good Versus Evil (2003). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Adolf Hitler and Cruella De Vil as the Black King and Queen face off against Martin Luther King Jr. and the Virgin Mary in Cattelan’s tongue-in-cheek rendition of Good Versus Evil, accompanied by, among others, Mahatma Gandhi and Che Guevara on the virtuous side and Count Dracula and Donatella Versace among the wicked. The eagle-eyed will note that Sigmund Freud makes an appearance on both sides.

![Abraham Palatnik, Quadrado perfeito [Perfect Square], 1962. © Courtesy of the Artist and Galeria Nara Roesler.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2020/12/Palatnik-chess-1024x683.jpg)

Abraham Palatnik, Quadrado perfeito [Perfect Square], 1962.

© Courtesy of the Artist and Galeria Nara Roesler.

PLAY IT BY TRUST aka WHITE CHESS SET (1966)

Play it for as long as you can remember

who is your opponent and

who is your own self.

y.o. 1966 pic.twitter.com/Wg5n3fi6b5— Yoko Ono (@yokoono) April 19, 2017

Chess is all about playing by the rules, and the Fluxus art movement, of which Yoko Ono was a key participant, was all about flouting them. Ono is also all about world peace, and so she converted a game about war into one about tranquility, with all-white pieces.

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Do you feel comfortable losing?) (2006). Courtesy of Christie’s Images, Ltd.

Chess relies on concentration, with players generally contemplating their next move in tense silence. Barbara Kruger turns this custom on its head, with each piece hiding a speaker that blares taunts like “You can’t be serious?!” and “What’s up with your hair?” Adding a bit of imaginary noise is the face of a screaming woman on the board itself, in place of the usual black and white grid.

Takako Saito, Small Chess Set (ca. 1964 – 1975). Courtesy of Christie’s Images, Ltd.

Fluxus art movement founder George Maciunas invited this Japanese artist to create a chess set in 1964. In a delightfully perverse move, Saito made all the pieces visually identical, but designed the piece to double as a spice cabinet, filling each one with a different aroma, so that you play by smell.

Damien Hirst, Mental Escapology (2003). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

In keeping with his fascination with prescription medicines, British giant Damien Hirst has transformed each of his chess pieces into a medicine bottle and, recalling other works that include surgical tools, used a surgical trolley bearing the chess grid as the table on which the contestants play. Chess grandmaster Jonathan Rowson has said that Mental Escapology “captures the unconventional truth that chess functions for many as a tonic, a medicine for the soul.”

Tunga, Eye for an Eye (2005). Courtesy of Christie’s Images, Ltd.

If you’re squeamish about body parts, you might want to avert your eyes from Eye for an Eye, by Brazilian titan Tunga. Based on the coincidence that there are 32 chess pieces and 32 teeth in the human mouth, Tunga has cast our own chompers as kings, queens, and pawns.

Keith Haring Chess Set, available at the MoMA Design Store.

If you’ve read this far, you’re a true enthusiast, so maybe you want to pass on your love of chess and art to the next generation. For just $38 at the MoMA Design Store and you can teach the young ones in your life about chess and contemporary art at the same time, with New York icon Keith Haring’s trademark barking dogs as pawns.