Art World

How the New Queer Asian American Criticism Is Shifting the Way We See Art

Artists and scholars shake up the foundations of art history in a new book, 'Queering Contemporary Asian American Art.'

Artists and scholars shake up the foundations of art history in a new book, 'Queering Contemporary Asian American Art.'

Terence Trouillot

In 2012, Jan Christian Bernabe, a Filipino-American artist and curator, and Laura Kina, a self-described “mixed-race Okinawan American” artist and scholar, met at the NEH Summer Institute at New York University. There, the two were part a three-week-long development program for teachers and academics, entitled “Re-envisioning American Art History, Asian American Art, Research and Teaching.” Sponsored by the Asian/Pacific/American Institute, the seminar was the genesis for Kina and Bernabe’s new book Queering Contemporary Asian American Art (University of Washington Press, 2017), which sets out to disrupt the conventional narratives of Asian American Art using queer theory.

“Within the Summer Institute, various groups started to form organically around some of the material that was being presented,” Bernabe told artnet News. “And our group was formed, called ‘Queering Asian American Art,’ because we just felt that the methodology used to critique and write about Asian American Art was lacking in theoretical foundations. And we thought it would be a good opportunity to bring in some queer theory, and to see how queer theory would inform our analysis.”

“It was sort of a nonstop discussion,” said Kina. “I think when you’re away for a month, the days run into evenings, and everyone is going out to dinner, continuing conversations over drinks and there was a real excitement brewing in the field. We’d all been showing together, exhibiting together, writing together in other capacities, and we wanted to capture this community that hadn’t yet been captured on the page.”

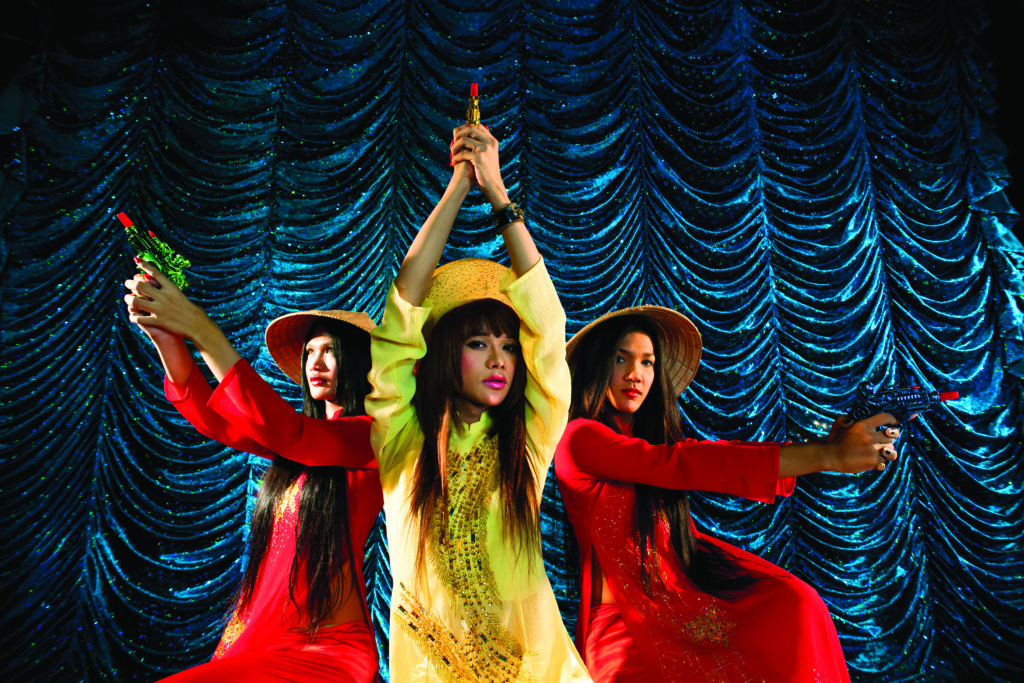

Jeffrey Augustine Songco, BOMH #1 (2009). Courtesy of the artist.

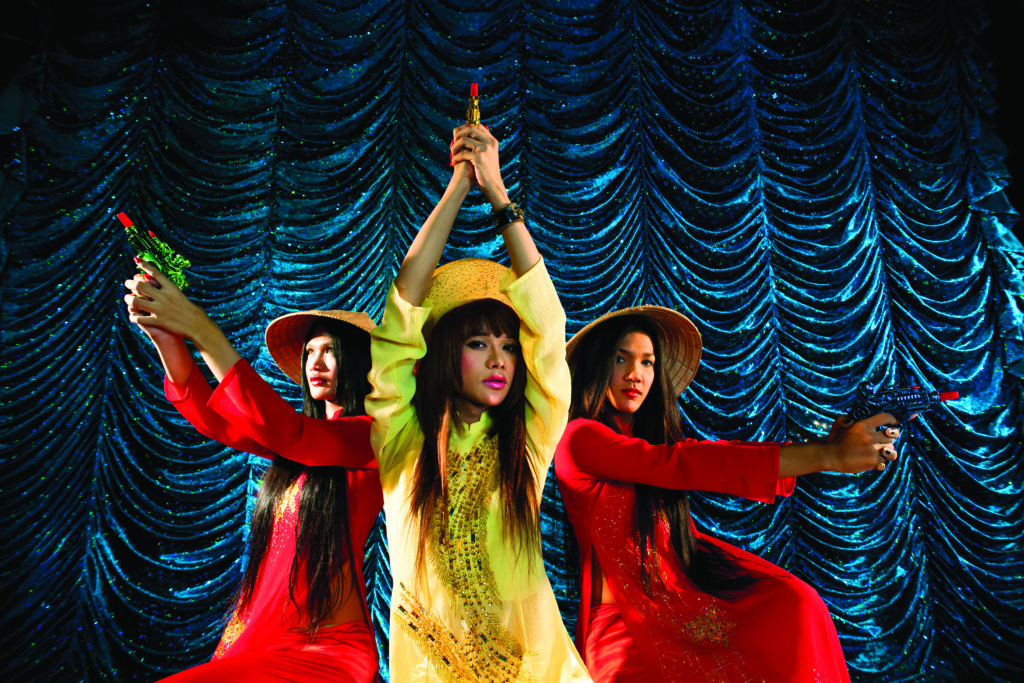

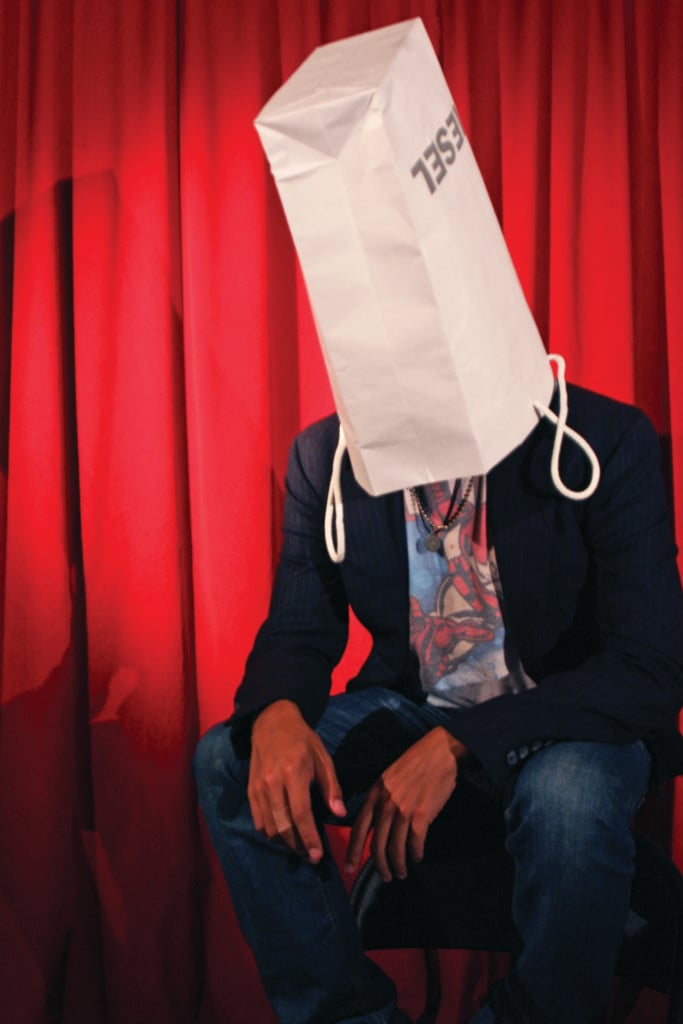

In the chapter “Queering Affect,” Bernabe’s essay “Filipino Diasporic Queer Killjoy” takes the work of Filipino-American artist Jeffrey Augustine Songco as a starting point to think about notions of Asian American queer identity. In both Songco’s BOMH (“Bag Over My Head”) series (2009) and his GayGayGay Robe (2011), the artist depicts himself concealed—covered by a shopping bag or draped in a rainbow-pride-colored KKK outfit, respectively—showing the anxieties of wanting to belong to a community but being torn between the different strands of his own identity: as Filipino, as American, as queer.

For Bernabe, Songco’s art “poses a challenge to… those who continue to embrace narratives of success and happiness while eschewing failure and failed bodies and missing the opportunity to nuance and show the affective stakes in identificatory practices of racial and sexual minorities.” In other words, Songco does not use positive imagery to discuss multiculturalism but instead focuses on the negative: the historical traumas of the Filipino diaspora in relation to race and sexual identity.

Jeffrey Augustine Songco, GayGayGay Robe (2011). Courtesy of the artist.

As a whole, the book focuses on how the queer perspective denaturalizes any number of categories, using the idea of “queering” as an operation to explore issues beyond gender and sexual orientation.

“The project isn’t purely recuperative,” Bernabe said. “We wanted to make a way where one could look at an artist and think about the work ‘queerly,’ and I think we laid that foundation down in the book where these questions pop up: What does it mean to do a queer reading? What does it mean to be Asian American and queer? And how do you take that all together using existing frameworks?”

In an essay by Harrod J Suarez, the works of artists Jill Magid and Hans Elahi are even considered to contribute to a queer Asian Americanist critique of surveillance. What does it mean to consider these non-Asian or non-queer artists through that lens?

The key comes in the notion, evoked throughout the book, that Asian American studies is a “subjectless discourse.” The idea (originally from another scholar, Kandice Chuh) is that the term Asian American is “subjectless,” insofar that it encompasses a multitude of identities across differences in race, gender, sexuality, class, and religion, shifting with each subjective context rather than having an objective essence.

In Elahi’s Tracking Transience (2003–present) and Magid’s Evidence Locker (2004–present), both artists decided to surveil themselves. Elahi captured every aspect of his life (where he eats, where he sleeps, where he defecates); Magid voluntarily asked the Liverpool police in England to surveil her using the cameras across city—and later sending love emails to the City Watch Operations manager.

Blurring the line between watcher and the watched, these projects become useful to a queer Asian Americanist critique of surveillance that focuses on defying the objectifying gaze of power, focusing on the subjective elements that resist simple classification: “By constructing an improper affiliation grounded in intimacy and desire rather than empirical data, these artists point to the limits of the purportedly objective comprehension of the surveilled subject/suspect.”

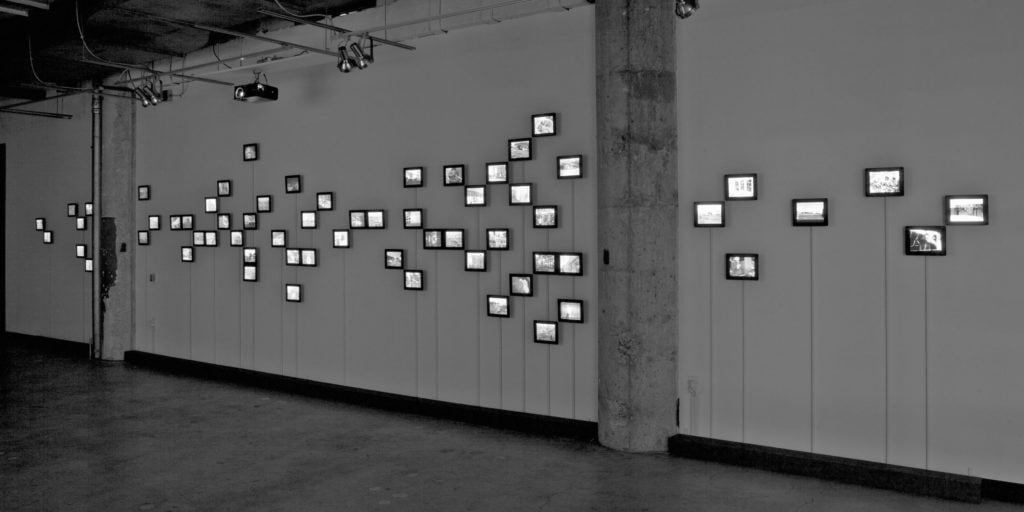

Hasan Elahi, Hiding in Plain Sight (2011), as installed at Intersection for the Arts, San Francisco, California. Courtesy of the artist.

“Our book is really about broadening the terms of Asian American, and also in a larger way, queering gender, race, sexuality, and citizenship; so I think that big questions of who can be a citizen and how, and what that looks like, and how can we form these strange coalitions, those were some of the things that sort of animated the project,” Kina told artnet News.

In the section “Queering Methodology,” art historian Alpesh Patel goes so far as to examine Cy Twombly’s work. The essay turns to Roland Barthes’s writings on Twombly as a way to understand the artist’s paintings as expressions of queer sexuality. Because Barthes interpreted the work through a Zen Buddhist perspective, Patel looks at ideas of a queer Zen within Twombly’s work, exploring ideas of identity and nationality through Chuh’s “subjectless” critique.

These are maybe startling examples to find in this book, but they relate organically to a larger point that the act of “queering Asian American art” challenges the very idea of what it means to be classified as part of a group.

A range of previous scholarship has covered the perils of notions of community identity. Miranda Joseph’s Against the Romance of Community (Minnesota University Press, 2002) showed how the rhetoric of “community” was used to reinforce traditional hierarchies of exploitation, while Ariel Goldberg’s The Estrangement Principle (Nightboat Books, 2016) warned that the label “queer art” was in effect another reductive classification.

But via its challenging and diverse reflections, Queering Contemporary Asian American Art shows how the specific questions of Asian American art history make the stakes of resisting a homonormative queer community (i.e. one that models itself after standards of success defined by white privilege and capitalism) even more vivid.

“We were really inspired by Karin Higa,” Kina explained, referring to the pioneer of Asian American art history who passed away in 2013. She tasked the younger generation of Asian American art scholars with collapsing established narratives of art history, telling them, “You guys are the termites of art history.”

That is, the new book sets out not simply to offer a “multiculturalist corrective,” but to eat away at the foundations of a white and heteronormative art historical canon.

Both Kina and Bernabe are in steadfast agreement: the collective practice of working towards social justice for an Asian American queer future is predicated on an alliance of hope and imagination—values that are quite fundamentally artistic.

In conjunction with the book’s release and Pride month, the Center for Art and Thought is hosting a virtual exhibition called “Queer Horizons,” featuring artists showcased in the book, and curated by Jan Christian Bernabe and Laura Kina.