Art World

Pioneering Cuban American Painter Rafael Soriano Gets the Catalogue Raisonné Treatment

Hollis Taggart will now be representing the artist's estate.

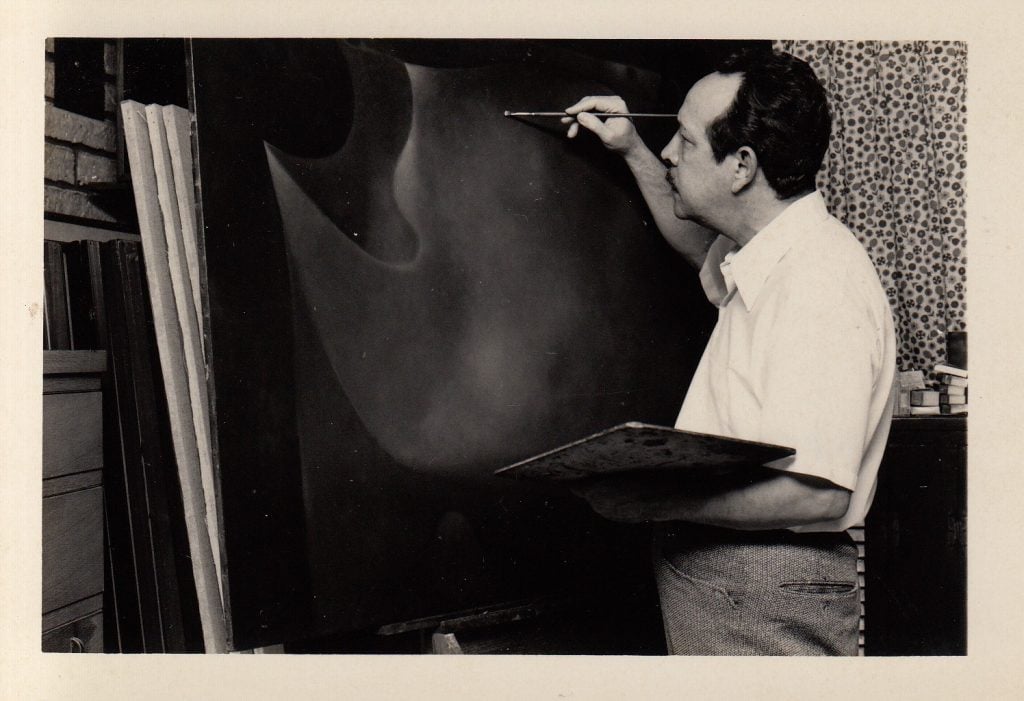

Nearly a decade after his death, the estate of Cuban American artist Rafael Soriano (1920–2015) is releasing a comprehensive digital catalogue raisonné of his work, from his hard-edged geometric abstractions of the 1950s and early ’60s to the more experimental, mystical canvases he made in exile in Miami.

The catalogue’s release also marks the start of a new chapter for the artist’s estate, which has signed with Hollis Taggart, the New York gallery known for its representation of Postwar American artists. The dealer staged a small show of Soriano’s work back in May, and will present a larger-scale solo show next June. (Miami’s LnS Gallery previously represented the estate.)

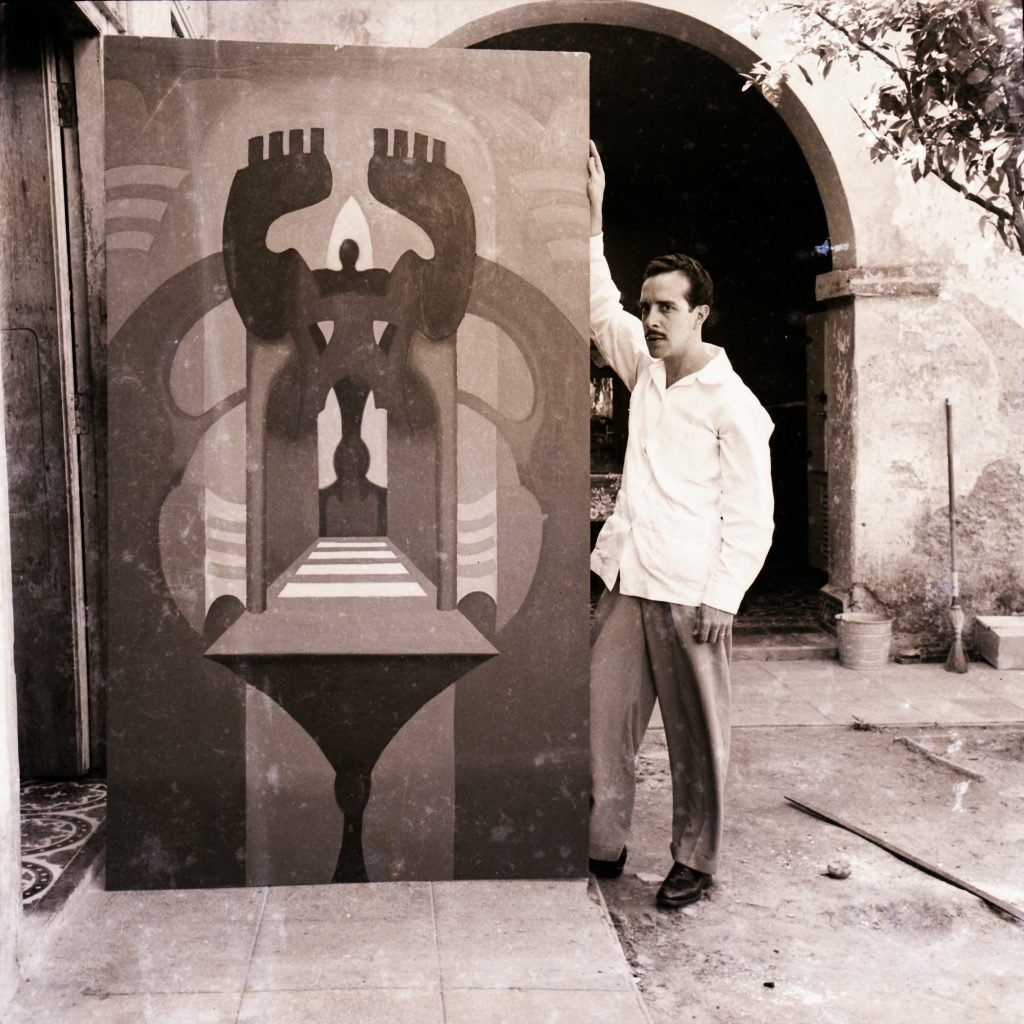

Soriano was a rising star in the Cuban art world in the 1950s, helping introduce the island to the concept of Concrete art, a geometric abstraction devoid not only of representation, but of symbolism as well. He was briefly part of the collective Los Diez Pintores Concretos, or the 10 Concrete Painters, and was also an important arts educator, cofounding the Escuela de Bellas Artes de Matanzas.

But after the 1959 revolution, the artist and his family, wife Milagros and young daughter, Hortensia, were forced to leave Cuba.

Rafael Soriano in Cuba (ca. 1949–50). Photo courtesy of the Rafael Soriano Foundation.

“He felt that he did not have any more freedom of expression,” Hortensia told me.

But free from Fidel Castro’s dictatorial regime, Soriano was able to forge a new beginning in the U.S.

“My parents were pioneers in the ’60s, with a group of other artists, establishing a real cultural scene here in Miami.… He was the artist, but my mother was the carpenter. She would make his frames. She would mount his canvases,” Hortensia added. ”They were a team.”

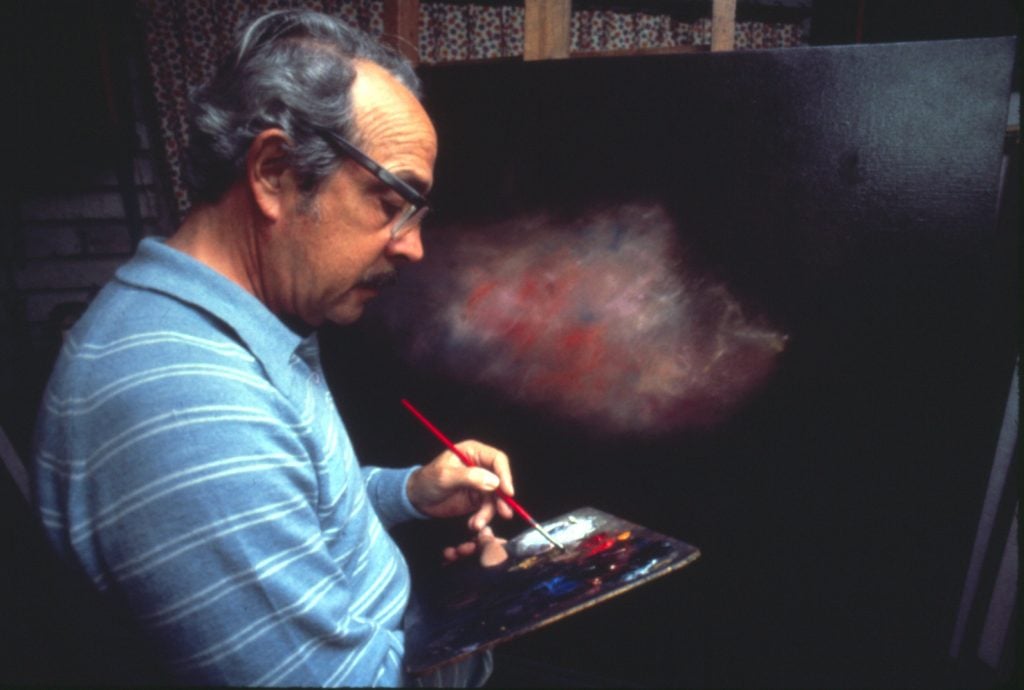

In Florida, Soriano initially struggled to continue his work, traumatized by the experience of fleeing his home country. When he resumed painting, it was in a new style, abstract but infused with his own unique sense of spirituality.

Rafael Soriano with his painting Flotando en el Astral in 1982. Photo courtesy of the Rafael Soriano Foundation.

“The anxieties and sadness of exile brought in me an awakening. I began to search for something else; it was through my painting,” Soriano said in a 1997 interview. “And I went from geometric painting to a painting that is spiritual. I believe in God, I believe in the spirit.”

“My father is one of the most important Latin American artists of his generation,” Hortensia said. “His work took on a great transformation once he came into exile, and he created a singular visual language. When you stand before Soriano, you know it’s a Soriano. You don’t mistake him for any other artist.”

The catalogue raisonné project took about four years, for which Hortensia enlisted art historian Alejandro Anreus to edit the publication.

Rafael Soriano as a 27-year-old in Cuba. Photo courtesy of the Rafael Soriano Foundation.

“It was an emotional challenge for me, because of course it’s going through my father’s entire lifetime,” she told me.

Fortunately, Soriano kept detailed records of his artistic output for his entire career, and the roughly 1,300 works he made in his lifetime.

In 1979, Soriano returned to Cuba for the first and only time, and was able to recover the records of the early years of his career that he had kept at his family’s house there.

Rafael Soriano, Doble imagen (Double Image),1968. Courtesy of the Rafael Soriano Foundation.

The Cuban period of geometric is the one most often targeted by forgers, Hortensia said. “I’ve had quite a number of people come and try to certify [Soriano forgeries] and if I don’t have it documented and it’s not in the archives, I don’t certify it.”

She sits on the board of the Rafael Soriano Foundation, which she helped establish in 2017 to safeguard her father’s legacy. The artist’s studio, where he lived and worked from 1965 until his death, is preserved exactly as he left it, and is open to scholars and academics. (The archives are promised to the Smithsonian Archives of American Art.)

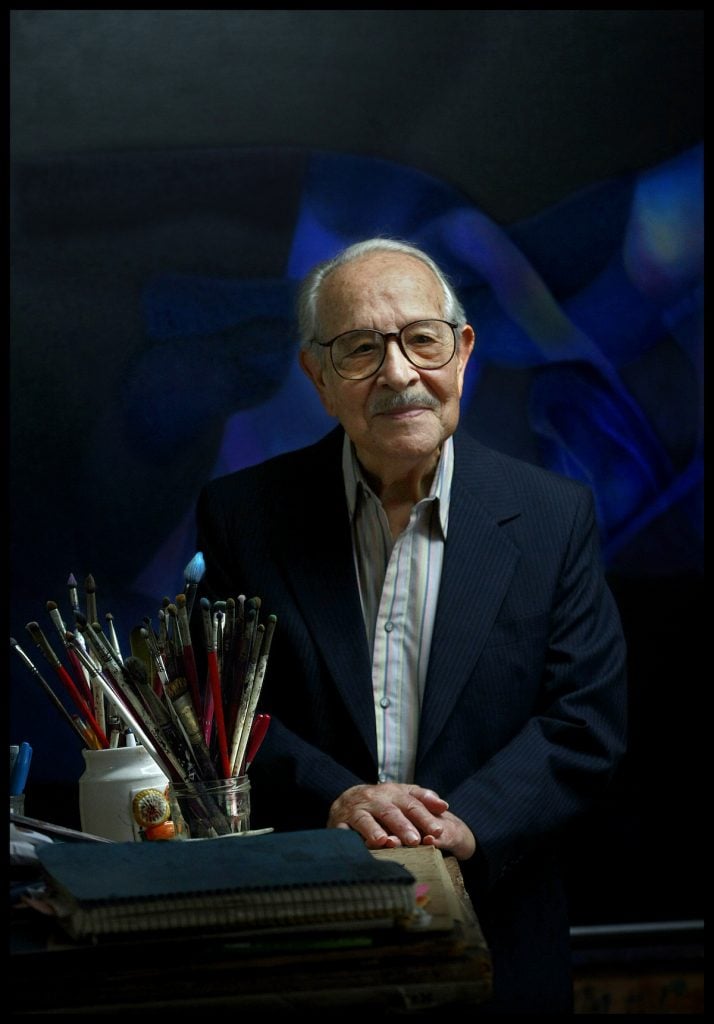

Rafael Soriano painting in the early 1970s. Photo courtesy of the Rafael Soriano Foundation.

“They can see where my father created his masterpieces,” Hortensia said. “His entire body of work was created in this humble home. They feel his essence when they walk in that little home.”

The catalogue begins with Soriano’s very first documented work, from age 14 in 1934, and his early explorations of Surrealism. It goes through to 2002, when the artist, diagnosed with dementia, made the decision to set down the paintbrush.

“I remember saying to him, ‘if you are not going to paint anymore, are you going to miss it?’ And he said, ‘No. Everything I was going to paint, I already painted,'” Hortensia recalled. “He went out on his own terms.”

During his lifetime, the artist held 43 solo shows and over 330 group shows. Since Soriano’s death, the artist has been the subject of a major traveling retrospective, “Rafael Soriano: The Artist as Mystic,” organized by the McMullen Museum of Art at Boston College in 2017. The tour concluded last year, at the Casa de América in Madrid.

Raphael Soriano, Luciernaga (Firefly), 1955. Collection of the National Gallery of Art.

Two major U.S. museums have recently added Soriano paintings to their collections. The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., acquired a trio of canvases representing three distinct periods of the artist’s career: the geometric 1955 piece Luciernaga (Firefly), La búsqueda (The Search) from 1968, and the late work El descanso del heroe (The Hero at Rest) from 1992. And the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York has added the 1970 painting La noche (The Night) to its holdings.

The catalogue raisonné, which will be free for anyone to access, launches October 16 with a private event at the Yale Club in New York.