Art & Exhibitions

The Story Behind RAGGA NYC, The Caribbean Queer Collective Seizing the Spotlight at the New Museum

The group is fostering a creative community of dynamic and talented people.

The group is fostering a creative community of dynamic and talented people.

Terence Trouillot

me: oh ok… so, ma, my friend chris has a group—let’s say, called RAGGA

mami: RAGGA?

The best of Artnet News in your inbox.

me: uh-huh. he’s jamaican, he throws parties and interviews people from the caribbean that are from the lgbt community, he asks them: where they’re from, how has their culture inspired their work, the connection between their work and their culture—and things like that… so he hired me for a party and interviewed me as well. that came out a couple of months ago. i was talking about how i felt as a dominican coming to the US after having lived in Santo Domingo for 6 or 7 years… and just about being dominican and how i felt about looking mixed, you understand?

This is artist Maya Monès talking to her mother. The conversation, originally in Spanish, is available to listen to as an audio recording (or read as a translated transcript) as part of a group exhibition at the New Museum, “RAGGA NYC: All the threatened and delicious things joining one another,” part of the Bowery institution’s just-opened fleet of spring shows (which also include Carol Rama and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye). Monès’s quote gives a glimpse of the community-building behind RAGGA, a loosely connected network of artists, poets, and designers that serves as both a creative group and support network for queer artists from a Caribbean background.

The “friend Chris,” mentioned in Monès’s dialogue, is multi-disciplinary artist Christopher Udemezue (Neon Christina), the artist and impresario who founded RAGGA NYC in 2015. (The name comes from the voltaic musical genre that originated in 1980s Jamaica.)

In a dynamic exhibition brochure, Udemezue gives his own picture of the ferment that brought the group together. RAGGA, he says, represents “a hybrid of ideas that began as late-night conversations over familial island roots, current social politics, empanadas vs. beef patties, pum pum shorts, scamming, and a longing for an authentic dancehall party that would also provide a safe space for queer Caribbeans and their kin.”

The two-part sound installation that makes up Monès’s piece, Ciencias Sociales (2017), mirrors this lively mix of concerns.

It includes intimate audio of Monès talking to her mom, revealing how her art practice functions as a way of thinking through her African heritage as a Dominican woman. Their dialogue plunges deep into a candid discussion about the rampant racism in Dominican culture against their Haitian neighbors, and their own African roots—what the artist calls a “cloudy sense of pride in a sort of racial limbo.”

But, at the same time, Ciencias Sociales foregrounds the artist’s ambient music, a song she recorded with conga drums called Mami, filling the gallery with melodic Afro-Caribbean beats.

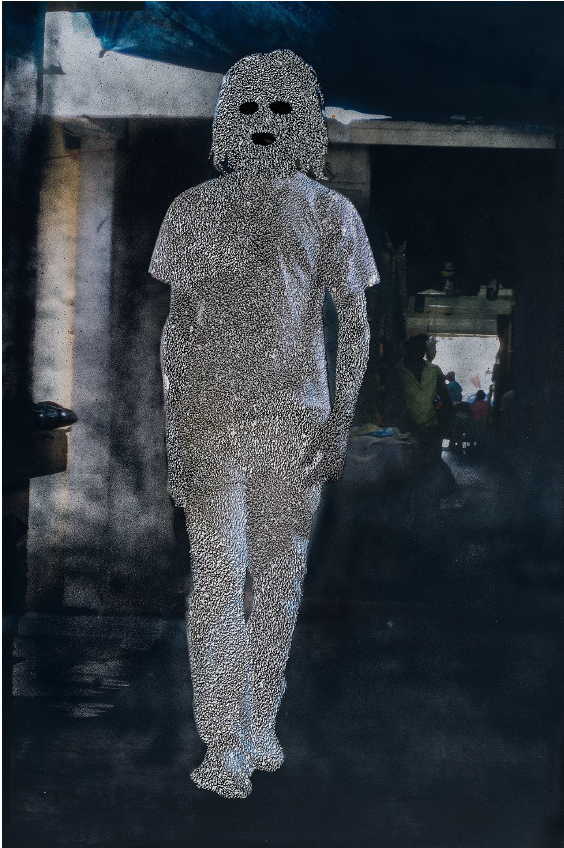

Paul Anthony Smith, Port Antonio Market #4, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Zieher Smith

Curated by Sara O’Keeffe for the New Museum’s residency program, the exhibition gives a sampling of the creativity marshaled by the RAGGA network. Multivalent in style, the show reflects the group’s emphasis on celebrating diversity, and its determination to wrestle with the racial complexities of Caribbean consciousness.

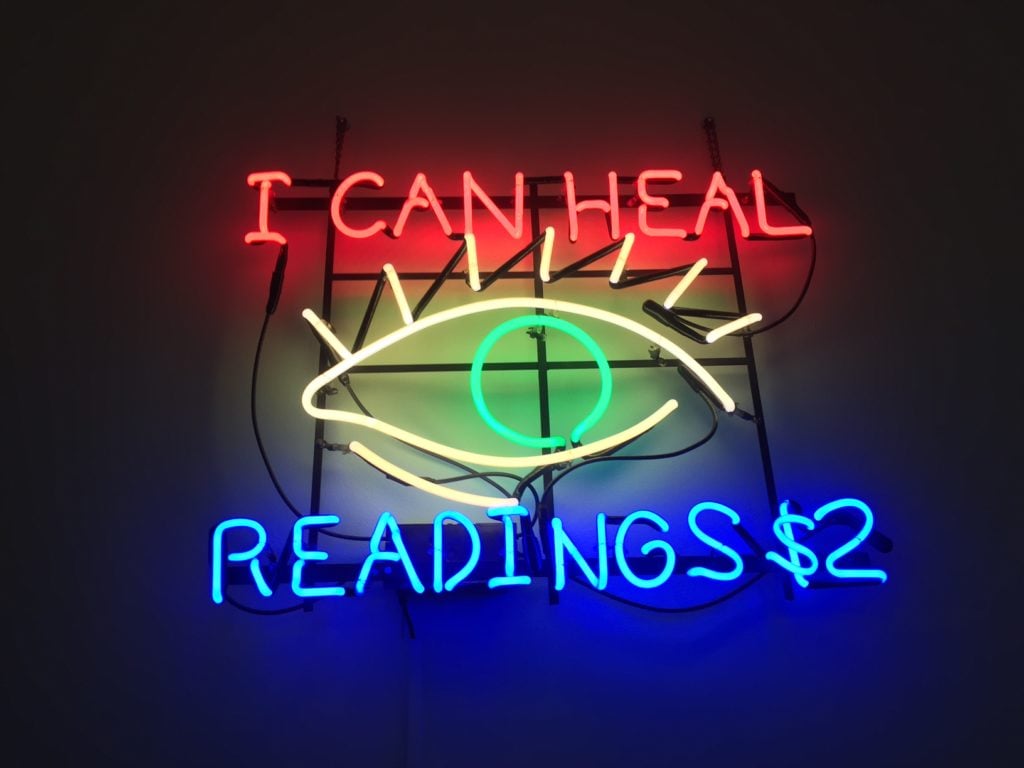

Renée Stout, I Can Heal (2000-2001). Image: Ben Davis.

Highlights include the sculptures of Renée Stout and Tau Lewis. Both look at creole traditions in the US. Stout’s work recalls the advertising signs of root medicine shops in New Orleans and DC, while Lewis offers an affecting marble portrait bust, presented on a plinth of cinder blocks, and with chains for hair. (The material is meant as a nod to so-called “creole marble,” mined in Pickens, Georgia, and incorporated into monuments across the country.)

Tau Lewis, Georgia marble marks slave burial sites across America (2016). Image: Ben Davis.

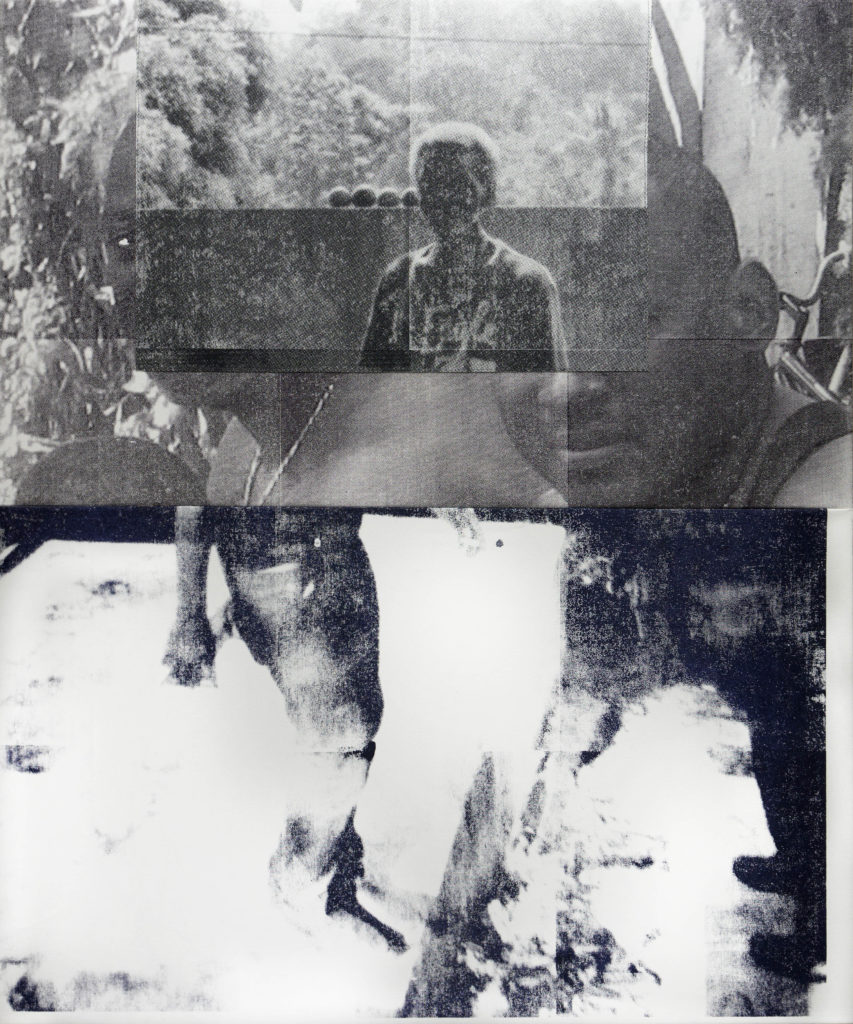

Paul Anthony Smith’s prints use a process called ‘picotage,’ a kind of pointillism where the points are torn or scratched off the surface of the work to create a textured pattern of white hatch marks. The artists also selects from his “Grey Area” series, silkscreen prints, reminiscent of Lorna Simpson, of scattered images of men he encountered in Jamaica at the time of this uncle’s funeral, with images of burial grounds.

Paul Anthony Smith, Grey Area #5, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Zieher Smith.

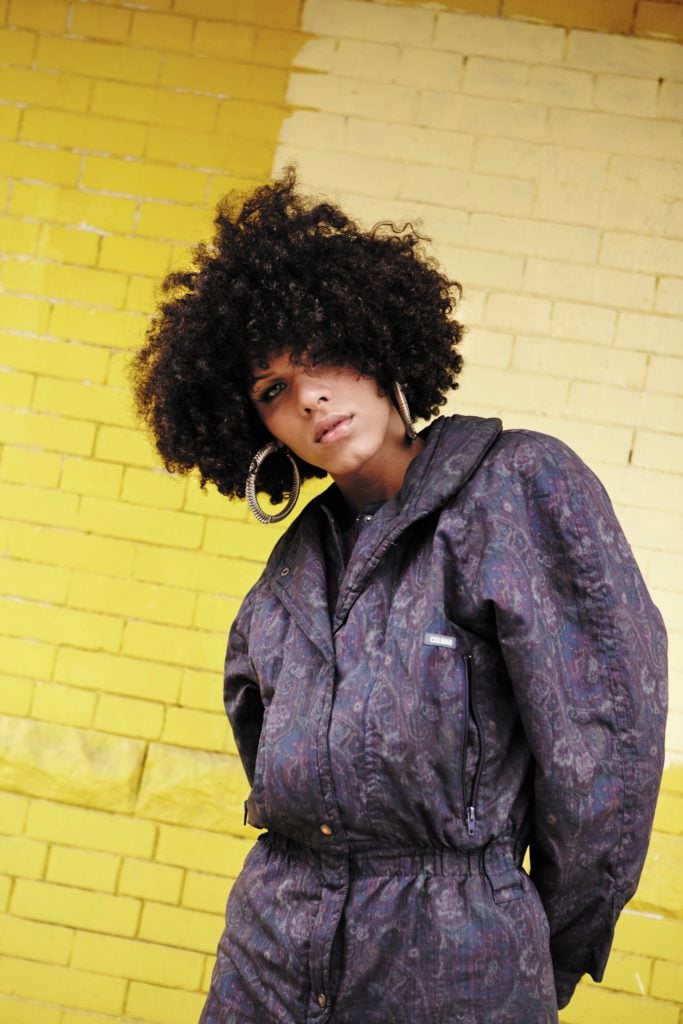

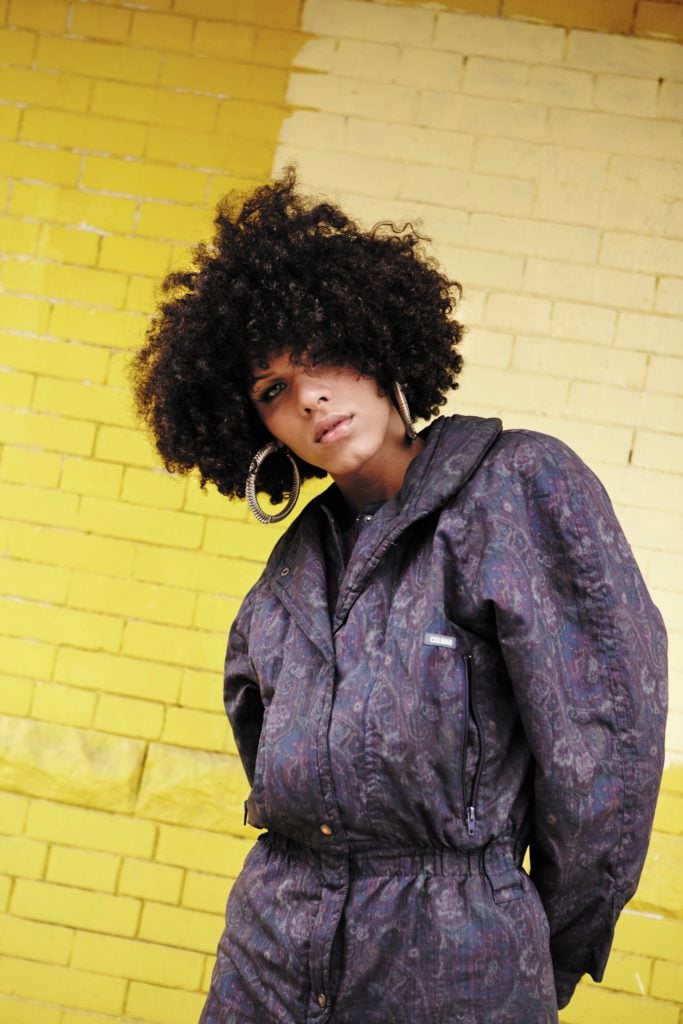

Udemezue’s own contribution are colorful set-up photos, imaginatively re-staging the Vodou ceremony at Bois Caiman, which marked the Haitian revolution, and depicting Queen Nanny, an Obeah woman who fled from slavery in Jamaica and became the leader of the group of escaped slaves known as the Maroons.

Christopher Udemezue, Untitled (Taken by the loa with a knife in her hand, she cut the throat of a pig and they all swore to kill all the whites on the island), 2017, Digital print. Courtesy the artist.

Christopher Udemezue, Untitled (In a trance, she walked out onto her reflection, closed her eyes and received a plan from beyond the mountains), 2017, Digital print. Courtesy the artist

Chaos-monde (2017), a collaboration between RAGGA artists Carolyn Lazard and Bleue Liverpool, incorporates an astrological map. A set of totems places on the map’s surface include leaves, sand, shells, and dried sugarcane, items that suggest Caribbean religious practice, which has been so important in claiming an identity in the face of both Christian missionaries and colonialism. The specific positions of these markers on the star map point to two days important in the assertion of Caribbean identity: January 1, 1804, the day independence was declared in Haiti, and October 27, 1979, the day St. Vincent gained independence.

The trick of the installation is that all this symbolically resonant stuff is barely visible, viewed only through a trap door in the floor that only lets you see fragments—a fitting metaphor for identities only now coming into view in shows like this one.

“RAGGA: All the threatened and delicious things joining one another” is on view at the New Museum, New York, from May 3 to June 25, 2017.