Art World

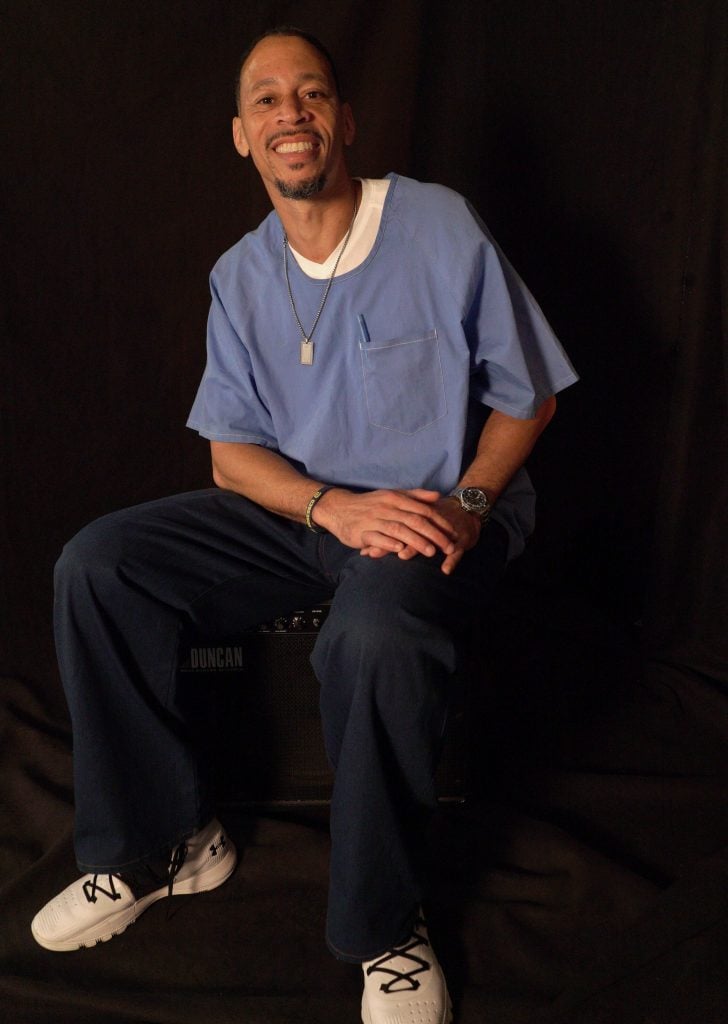

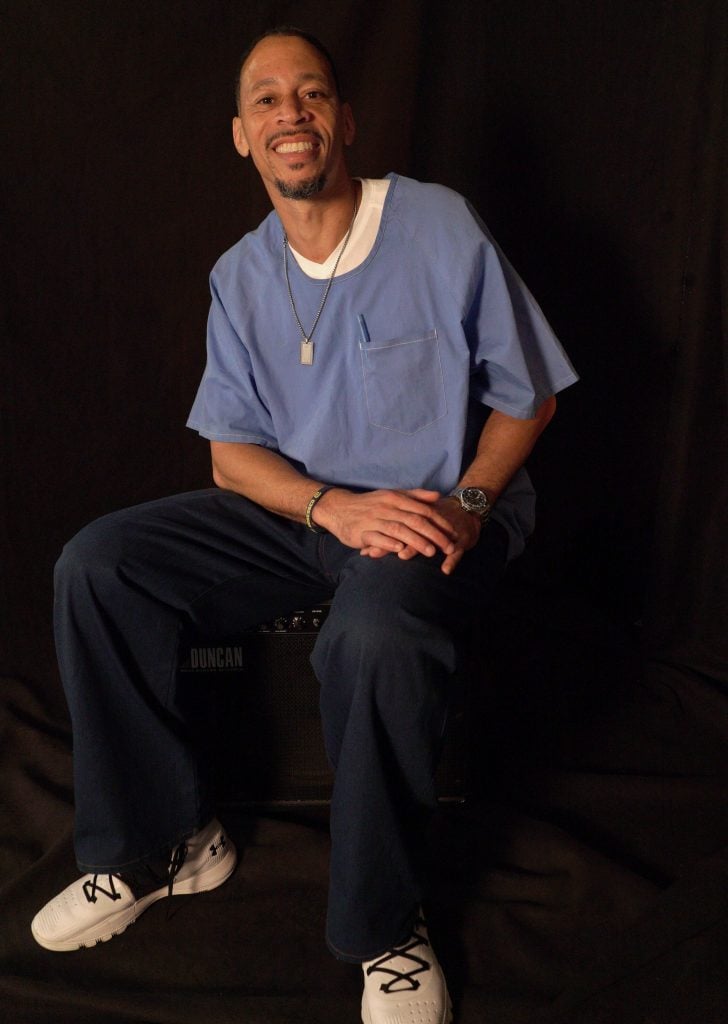

‘We Can Add Value to the World’: San Quentin Prison Inmate Rahsaan Thomas on Why He’s Curating Art Shows From Behind Bars

Thomas's spoke recently with Andrew Goldstein on the Art Angle podcast.

Thomas's spoke recently with Andrew Goldstein on the Art Angle podcast.

Andrew Goldstein

For Rahsaan “New York” Thomas, success came later in life—and at a cost. After being incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison in California, Thomas began to work with organizations and initiatives using creative forces to combat mass incarceration and shift attitudes about prisoners from the inside.

He is now the co-host of the Pulitzer Prize-nominated podcast “Ear Hustle,” co-founder of Prison Renaissance (which connects prisoners to people outside), contributor to multiple national news outlets, and staff writer at the San Quentin News. He has written about the devastating impact of the coronavirus on prisoners and the prison system for Insider, the Prison Journalism Project, Current, and more.

Before the New Year, Thomas spoke to Artnet News editor in chief Andrew Goldstein about art, empathy, and his acclaimed curatorial debut with the online show “Meet Us Quickly: Painting For Justice From Prison,” on view through January 31, 2021 via the Museum of the African Diaspora San Francisco.

A longer version of this conversation aired on the Art Angle Podcast.

Could you describe exactly where you are and what your surroundings are like?

I am calling collect from a phone booth at San Quentin State Prison, and about three feet from me there’s a yellow line that says “This is out of bounds.” Looking in front of me through clear glass, although it’s dirty, I can see the other guys on the first five phones nearest me.

How many of them do you think are on podcasts right now?

I’m confident to say that I am the only one talking on a podcast right now.

You have curated an extraordinary exhibition of work made by incarcerated artists, and I definitely want to talk to you about that, but first can you tell me about the series of events that resulted in your being at San Quentin?

Oh that’s deep. To make a long story short, basically I had some character flaws. I had a rough childhood growing up in Brownsville, New York. I was beat up a lot, exposed to a lot of fighting, and I started fighting back.

I wasn’t trying to be tough; I was fighting for acceptance. I felt like if I was hard enough then I would probably be respected. The last straw for me was when my brother got shot—we were being robbed and instead of cooperating I fought back. I felt like if I let them rob me, I’d be seen as weak and soft, and so I tried to fight and got my brother shot in both legs.

That put me on a path of carrying guns. Fast forward to 2000, and I was the type of person that carried a gun, not only for self defense, but to defend my identity. At that point, I became known as somebody that you don’t mess with. I carried around that gun to defend that identity at all costs, and some things happened between me and two men who were also armed, and I ended up killing one of them.

You’ve now served nearly 20 years of your sentence, and during your time in prison, you’ve accomplished some truly remarkable things. Just to name a few: you are currently the co-host of the Pulitzer Prize-nominated podcast “Ear Hustle,” you’re producing a short film for the Marshall Project, an organization you also write for, and you’re about to finish your college degree. Have you always been such a Renaissance man?

No, no. On the streets, I didn’t know what my number one purpose was. I was lost. I had jobs, but I never had a career. I had two jobs, two kids, just floating and lost.

So it was crazy to have to come to prison, that it took so much pain in order for me to find myself. There’s something [the actor] Chadwick Boseman said about how the struggle prepares you for your purpose, and that really struck me. Now I embrace my struggle and I look for a way to make something good come out of it.

I’m driven by purpose, to just accomplish as much as I can.

You are clearly very ambitious and you’ve accomplished a lot of things that are remarkable. I mean, you completed the first full marathon at San Quentin, is that right?

[laughs] No, no. I have completed a marathon in San Quentin and I have the record for the slowest time—ever. Many people definitely have completed a marathon before me, especially that day.

A lot of people who don’t have personal experience with incarceration may not really understand exactly what prison life is like. We watch movies and television, of course, but what is it actually like?

What people don’t know is that most of prisoner life is boring. A lot of chess games, a lot of pinochle, a lot of working out, a lot of wishing we had Netflix or anything on cable. It’s a lot of wasted time, and the feeling like “damn, my life has gone away.” I took a life, and that was a waste. And now I’m wasting my life. It’s just waste, waste, waste on top of waste.

That’s one of the things that drove me to make purpose out of this thing and see it as an opportunity to better myself. Like to start reading, to get into yoga, and find my spot. Instead of wasting time, how can I serve society? Because sitting in the cell costing society $80,000 dollars a year is not paying my debt.

So that brings us to your current exhibition. It’s called “Meet Us Quickly: Painting For Justice from Prison” and it features 21 artworks by 12 incarcerated artists. How did this exhibition come about?

Proximity. It came about through proximity.

Bryan Stevenson, the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, came here one time and made a speech, and one of the things I took from him that day is that if you want to solve a problem, you have to be proximate to it. And I realized that I have to get people to see us as people, and see a value in us. If people want to come in here and work with us, and go to all the trouble it takes to arrange that, making collect calls etc., we have to do something that gives value.

The questions I’m asking are simple. What can I write? What can I do? What can I say? What can we accomplish together? And so in that vein I was working with a woman named Taina Angeli Vargas, who co-founded the organization Initiate Justice, to get incarcerated people to understand how the system had impacted their ability to vote.

Working with Flyaway Productions, she wanted to do something with Black and Jewish people uniting to fight against mass incarceration. She put a call out for assistance and, through a web of connections, it hit Prison Renaissance’s ears. I ended up getting a letter in the mail with a fancy logo, and Jo Kreiter, the artistic director, told me what they were trying to do. One of the partners was the Museum of the African Diaspora and I was in.

Where does the title come from? What does “Meet Us Quickly” mean? And what does “painting for justice” mean?

The paintings for justice part I definitely added on my own, but “Meet Us Quickly” was Jo’s idea. It’s part of a trilogy of outdoor aerial dance performances that address mass incarceration called “Meet Us Quickly With Your Mercy.”

So how did you choose the artists in the show and how did you choose the artworks?

I’m not a professional curator. This is my first time curating anything, so I just went with my eyes and chose what spoke to me. I’ve long been a fan of several artists here at San Quentin, like Antwan ‘Banks’ Williams, who I work with on “Ear Hustle,” Lamavis Comundoiwilla, and O. Smith, to name just a few.

Bruce Fowler did a painting of a sun in a cage in 2018 that appeared on the CBS morning show, and I’ve been a fan of his ever since. Lamavis taught himself how to think and learned how to paint here at San Quentin, and now he’s reading all these books on Impressionism and applying it to his paintings. He created a style called “Fusion,” which uses multiple styles in one painting. These guys are amazing.

You mention Bruce Fowler, who has a portrait of the late Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg included in “Meet Us Quickly.” In his artist’s statement, Fowler calls himself RBG’s “most unlikely admirer.” What is the story behind this painting?

I think that would be a question best asked of Bruce, but what little I can add is that, I mean, that’s a Supreme Court judge, right? And we’re incarcerated. Judges and courtrooms and DAs are not things you’re usually a fan of. Especially when you first get incarcerated you’re like, “Man, even if I did it, judge, that’s a lot of time!” And so I think that’s one of the reasons why he calls himself an unlikely admirer. I think there are other reasons, but I’d rather leave that to Bruce to talk about, but it’s one of my favorite paintings in the exhibit, and I’m definitely an admirer of RBG as well.

And what about Antwan ‘Banks’ Williams, who is also the co-creator and sound designer for “Ear Hustle.”

He’s one of the most talented people I know, talk about a true Renaissance Man. He does everything from clothing design to filmmaking, directing, drawing, creating music.

It is interesting that, along with Earlonne Woods, the podcast’s third co-founder, is Nigel Poor, who is a Bay Area artist and photographer. And I wonder if it’s possible that “Ear Hustle” itself is an art project of sorts.

Nigel definitely has an artistic mind being a photographer, and he brings that creativity to the production. That artist’s point of view is definitely incorporated into every story, and it definitely is the lens we look out of.

I hadn’t thought of it before, actually this question kind of surprised me, but I’m realizing now that the way we put the stories together, it is a work of art, because we take something that people either think of as ugly and horrible, or totally disregard and don’t think about, and we put it in people’s consciousness. That is something beautiful, and I do think that is a work of art.

Inmates listen to graduates of San Quentin Prison’s The Last Mile program. Photo by Michael Macor/San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images.

You’ve written about the empathy-building power of art, the way that art can help people have a greater empathic response towards the subject. Can you talk a little bit about why that matters, especially when it comes to art by prisoners?

First of all, they say the eyes are the window to the soul, right? Whatever the artist does, he paints his soul onto that canvas. He takes what he sees and gives it to the world. And when you see that, I think you see the humanity of people.

Empathy is very important because I know nobody wants to hear like, “Oh my mom beat me. I grew up in a rough neighborhood so I had to rob people.” Nobody wants to hear that crap. And that’s understandable, because it’s not excusable. We have to be accountable, no matter how rough our lives were, we must never give away our power to make the right choice. And so we are responsible, that’s 100 percent true.

But the other truth is that most crime doesn’t happen because people are evil. Most crime happens because people are traumatized, because people are poor and isolated and lack opportunities. And so if we’re not empathetic to the reason why crime happens, then we’ll continue to have a flawed system that seeks to punish crime after it happens. Somebody’s dead, somebody else goes to jail. Two lives are wasted—but if you’re empathetic to the root causes of crime, and you address them, you stop crime before it ever happens, because you address the root causes of it. That’s the kind of system I would like to see.

I mean, I’m literally in a prison with I don’t know how many lifers running around free pretty much all day long. It’s one of the safest places I’ve ever been because guys do these programs and they deal with their trauma. They make social connections and do vocational groups and take education classes. They go home and they don’t come back, all of my friends are doing amazing things out there. There’s about 100 of them outside right now, and none of them are coming back.

That’s a very noble goal for the exhibition to raise this spirit of honor when it comes to the incarcerated, but there’s also a more practical aim, which is that the artworks were auctioned off at the end of the show run. What do you hope to achieve with the auction?

I hope that people see the value of incarcerated art. The auction did decently, only five or six of the paintings sold. So maybe the opening bid was too high, but I felt it was important that we have opening bids that respect the value of the artist’s work. I’ve seen on TV artwork that sold for $20,000 to $30,000—really good money—and I felt like that these artists are just as good and the art shouldn’t be judged by the stigma of prison. It shouldn’t be belittled or undervalued because of that.

So here’s a little bit of a philosophical question. As we all know, people in prison are there for a wide range of reasons, some serving mandatory sentences that are unduly harsh, some are even actually innocent. And then on the extreme opposite end, there are some who are serving time for committing truly heinous crimes. What do you make of the phenomenon where the more reprehensible or infamous an artist in prison is, the more demand there seems to be for their work in some ways?

Yeah, I don’t understand it. But that’s the world we live in. You know, you can get millions of dollars for being in the movies, but $30,000 a year for being a teacher. But I definitely would like to figure out like how we can get our artists valued on that level as well. I think I would even go as far to say that I think that the guys who I know, who are ready to return as productive citizens, are probably more deserving.

That raises the question, do you think that art by anyone, no matter who they are or what they’ve done, is something to be celebrated?

I would ultimately say, yeah. You know, I sat down with “Ear Hustle” and did an interview with someone who molested children, and when you hear how they got to that path, you think of it differently.

Like, yo, that’s not cool. I’m not gonna let you be with my kids, but then I can’t judge you, because if that happened to me, who would I be? And so we’re just judging people by the worst thing they’ve ever done. Maybe they have psychological issues.

I don’t know why a human being would do certain things, but I do know a lot of good people who’ve done bad things, and it’s just a matter of dealing with the issues. So it’s just really hard to judge and make a blanket statement, but I think that separates the art from the artist.

You’re speaking like a true curator.

Thank you.

Andre Hill’s daughter, Karissa Hill, addresses the crowd at a press conference and candlelight vigil for her father outside the Brentnell Community Recreation Center in Columbus, Ohio. Photo by STEPHEN ZENNER/AFP via Getty Images.

This year’s protests over police violence have galvanized public attention on the front end of the legal system, but the conditions of the incarcerated, and the forces that shaped their sentences, is still not something that is front and center in the public imagination.

However, the statistics around America’s prisons are absolutely shocking. The United States has 2.3 million people in penal facilities—the largest number in the world. Black people constitute 33 percent of the prison population, despite only being 12 percent of the overall population. And, according to Michelle Alexander’s book, The New Jim Crow, one out of three black men should expect to be incarcerated within their lifetime. What do you think people need to know about the carceral state in America today?

I think that what people don’t understand is that our policing problem is tied to our incarceration problem. They’re married. A lot of times we see people marching against police shootings of unarmed Black men, but there’s no uproar when Black people shoot other Black people, which has much higher rates. But they’re the same issue. Growing up in my neighborhood, I never felt like the police cared, or that they were ever going to protect me. And so I felt like I had to protect myself, and going to the cops would make me a snitch.

Right now, we’re marching for reforms, but going after police officers is just the wrong attitude. An officer who goes to work with honest intentions to do a good job of protecting society shouldn’t end up with manslaughter charges because they’re not trained to deal with a certain situation. The problem is not individual police, and I’m speaking broadly, I’m talking about the average cop who might just be scared or might have some racial bias and be unconscious of it, which is natural as human beings. We don’t like it, it’s not cool, but we’re human. The problem is we need to rethink policing. Like I was saying earlier, policing is about punishing crime with violence.

I think that a lot of prison time is unnecessary as well. I’ve seen people rehabilitate in five, 10, 15 years. You can change a person’s whole mindset. You don’t need to have people in here for 30, 40, 50 years… we’re paying for that. We’re paying $80,000 a year in California for that at a time when money should be going to COVID. And so I feel like the policing problem just needs to be addressed more. We need to stop going after individual police and go after the whole system of policing.

You mentioned earlier an organization you founded called Prison Renaissance. What is that?

Prison Renaissance is about is the organization that I started on the yard with Emile DeWeaver and Juan Meza. It’s about finding a way to connect incarcerated people, artists in particular, to society and communities that need us. We take part in conversations dealing with mass incarceration or social justice issues or things that we’re experts on, so we can add value to the world.

You said the phrase, “connect incarcerated people to the communities that need them” and that’s a quote from the mission statement. It’s an interesting phrase because typically you think of inmates as being the ones who are in need rather than the free communities that are outside prison walls.

I read a story in the New York Times about a brother from Queensbridge [the public-housing development] who was formerly incarcerated and two guys in the neighborhood were going 10 paces, which means they were backing away from each other, they both had guns like in the wild, wild west—they were getting ready to shoot each other. And this guy got between them and broke it up, got them both to leave and then mediated with each one. He got them to squash this beef without anybody going to prison and nobody getting shot.

Queensbridge went a year without any shootings, and it’s one of the biggest housing projects in New York City. They also credited part of that to the cameras they have set up, so I want to mention that, but I just thought about the fact that only a guy who’s been there, who has street credibility, who changes his life could do that.

I’m part of a program called Squires here at San Quentin and we talk to kids that come from rough situations, who came in like two Saturdays a month, pre-pandemic. And they open up to us and tell us stuff they’ve never told anybody, about the emotional issues at the root of their bad behavior. And the reason why they do that is because we tell them why we’re here, not the glamourized story, but the real story: “I was hurting. And I reacted like this because I went through this and that.” They realized that and think, “wow, these guys understand this,” and they open up.

Nobody else on the street can get these secrets out of them, so we have a value to society. In many ways we know why we did wrong. We know where we are, how to fix the problems, and so we’re included in more conversations. That is something underutilized.

Branden Terrel stands in his cell on June 8, 2017 in San Quentin, California. Photo by Ezra Shaw/Getty Images.

There’s a Freedom Fund for Rahsaan “New York” Thomas, which has an incredible start as of now. What is your personal path forward? How are you positioning yourself to be able to go out in the world and give back to the community?

I plan to do that on both a macro level and a micro level: multimedia, working on the podcast, in film, documentaries, writing, and telling and stories that address social-justice issues in creative ways. I want to continue counseling, stay connected, and understand the nuances of whatever they’re going through. And then I’m going to still do a social justice stuff on the side, like direct advocacy, looking to get laws changed, sit down with politicians through whatever means I can.

In my neighborhood, seven out of 10 people went to jail. So the odds were pretty good, but I’m exceptional. All right. You can’t apply exceptionalism to me because I’m one of the guys that should have made it in the first place. Instead, I became part of the problem, and so I’ve got to make up for that. I have to take full accountability for that and do everything I can to fix it. And I can’t never really fix it. So it’s something I’m going to die paying for.

With your exhibition, you’ve chosen to use art as a means of raising awareness about the lives of the incarcerated, and yet the world’s top art institutions are actually kind of ambivalent when it comes to incarceration.

I think a perfect example is that just now MoMA PS 1, a museum in Queens has this show called “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” but at the same time, one of MoMA’s trustees, Larry Fink, is personally financially invested in private prison companies. What do you make of that?

I’m definitely against financing incarceration. There should be a separation between people profiting from incarceration and trying to display the humanity of incarcerated people. It sounds pretty contradictory to me.

It sounds pretty contradictory to me, too.