People

Documentary Shows David Hockney’s Rage Against the Art Machine

There's shockingly-intimate archival footage.

Photo: Richard Schmidt/Film Movement.

There's shockingly-intimate archival footage.

Sarah Cascone

Randall Wright’s documentary Hockney offers a deeply personal portrait of the British artist. And yet, viewers may see less of David Hockney in action than they would expect.

The focus, instead, is on the all-encompassing creative passions of one man, on both his personal struggles and triumphs. Wright has made a film that is perfect for Hockney’s existing fans, but does not serve as a much-needed primer on the artist. In this way, the filmmakers seem unconcerned with establishing Hockney’s career trajectory or exploring his place within the art historical canon.

Instead, the BBC documentary was described by BBC controller Kim Shillinglaw as a “frank and unparalleled visual diary.”

David Hockney, My Parents (1977).

Photo: courtesy David Hockney.

Despite its flaws, Hockney’s life makes for compelling cinema. There is love, there is heartbreak, and there is tragedy (in the form of the AIDS crisis), even as career milestones are glossed over.

A child of the Depression “brought up in austerity,” as he himself put it, the Yorkshire-born artist moved to the US as a young man, living first in New York, and then California, where he fell in love with Los Angeles. “When I arrived here, somebody said ‘why have you come to his cultural desert?'” Hockney recalled in archival footage, explaining that he was drawn to the magic of Hollywood when he was growing up.

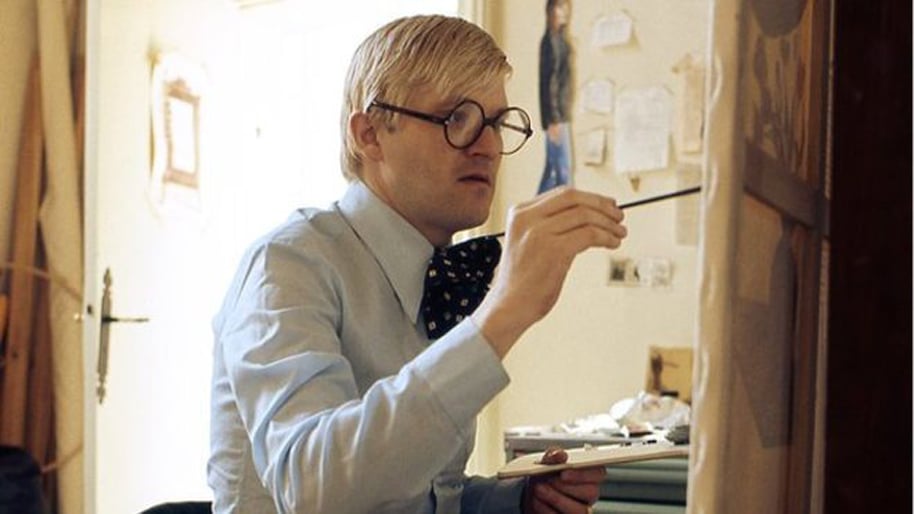

David Hockney in a still from Hockney.

Photo: courtesy Randall Wright.

In the film’s earliest moments, a friend describes the artist as “a Russian peasant, a right Boris!” It’s a fitting introduction to a man who has been dying his hair platinum blonde since watching a Clairol TV ad in the 1960s that said “everybody should go blond,” who has been so devoted to depicting LA in his work.

Unfortunately, we couldn’t tell you who described the artist so colorfully, because it’s incredibly difficult to keep track of who is saying what in Hockney. Identifying title cards appear only sporadically, and never explain the speaker’s relationship to the artist.

David Hockney, Portrait of an Artist ( Pool with Two Figures) 1972.

Photo: courtesy David Hockney.

You might recognize the artist Ed Ruscha, but Wright isn’t about to tell you who he is, or why he’s an authority on Hockney. In another scene, there’s a great story about Hockney spilling ink on a college friend’s parents white carpet—”Dad, we should have him sign it! It’ll be worth millions in a couple of years!”—but good luck figuring out that friend’s name.

This approach feels diary-esque, in the way a journal keeper might refer to acquaintances by first name alone, without introductory preamble or helpful exposition. Hockney’s jarringly-personal archival video footage also makes an appearance in the film, without explanation.

The poster for Randall Wright’s David Hockney documentary, Hockney.

Photo: courtesy the BBC.

However, Wright’s incorporation of these home movies, as well as old photographs, is among the film’s highlights. Adorable video of a young Hockney dancing at a college party is followed some time later by a shot of the artist walking down the hallway of his London apartment, casually stripping off his underwear to slip into the shower.

When Hockney breaks up with his first love, Peter Schlesinger, his heart-wrenching sadness is captured on film, the artist lying on a waterbed, crying on the shoulder of his best friend, curator and art critic Henry Geldzahler.

David Hockney, Arranged Felled Trees (2008).

Photo: courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Hockney was also deeply affected by the AIDS crisis, which he says claimed the lives of perhaps two thirds of his friends. “When I think of all those people… New York would be different” had they not died, Hockney said. “There would be Bohemia still.”

In the face of such tragedy, it was art that allowed Hockney to keep going. “The art is the thing that gives him the anchor in his life and in the the world,” said one friend. The primal, almost life-giving importance that art has to David Hockney is more significant to his career than any auction record or museum retrospective.

David_Hockney.

Photo: Film Movement.

“I’m interested in ways of looking,” said Hockney. “Everybody does look, it’s just a matter of how hard they’re willing look.”

The drive to effectively communicate what he sees has pushed Hockney to explore many different means of image-making, often by finding new and unexpected uses of technology, from photos and photocopiers to HD video cameras. His current iPad paintings, for instance, were presaged by his use of the fax machine, which he once used to transmit an entire work to an exhibition in South America.

David Hockney painting Woldgate Before Kilham, a Yorkshire landscape, in 2007.

Photo: Jean-Pierre Goncalves de Lima/Film Movement.

There’s another reason Hockney has produced such radically different series of works over the years, a friend in the film noted: “He does not want to become a machine for producing items of value.”

This idea is what drives the artist, but it is unfortunate that so much of his professional life is missing from the film.

Hockney is currently in limited release, and is screening in New York at the Metrograph and the Film Society Lincoln Center.